29.2 x 40.6 cm

Inscriptions

signed, ‘Suzor-Coté’ (lower right); inscribed, ‘Ébauche de Suzor-Coté/Bénédiction des érables/L’original ‘c à dire le/tableau’ est au musée de Québec’ (verso, centre)Provenance

Eugène Côté, brother of Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté

Arthur Côté, nephew of Marc-Aurèle Suzor-Coté

Madame Cécile Vallée Côté, wife of Arthur Côté

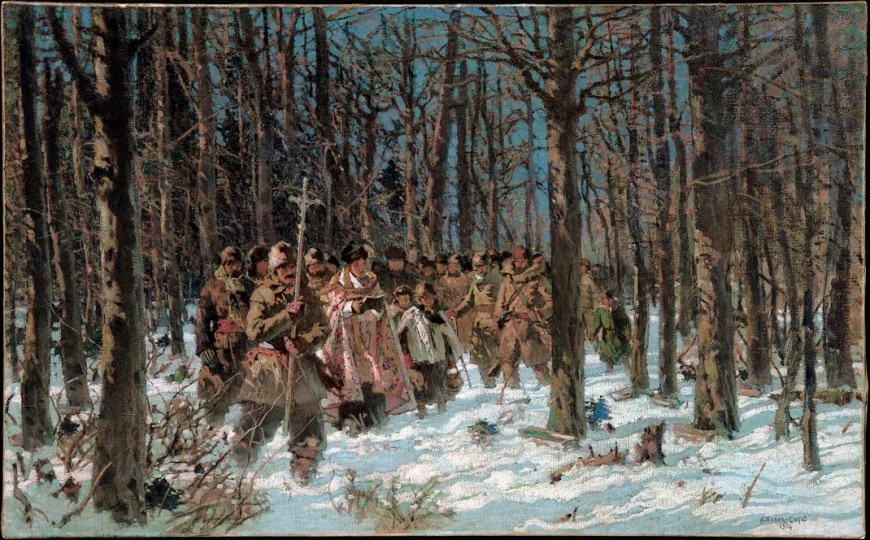

Suzor-Coté titled the painting La Bénédiction des érables, vieille coutume canadienne-française disparue, which was featuredat the 42nd Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibit, held at the Art Association of Montreal in November 1920. The title suggests that he never witnessed the extinct custom, which he depicted in great splendour.

The priest, dressed in a glittering gold and embroidered cope, is flanked by an altar boy and a man carrying a processional cross. He is praying to Providence that the trees will produce an abundance of sap that will be made into maple syrup, taffy and sugar.

In The Year Book of Canadian Art 1913, Lintern Sibley commented on this unfinished composition while it was still in the studio, recalling the painter’s words:

Nothing enthuses him [Suzor-Coté] like his own ancestral country and the old customs of his race — now, alas, falling, many of them, into disuse. At this writing he is engaged in painting a huge picture depicting one of these of customs — the blessing of the maple sugar bush. It used to be the custom when the last snow disappearing for the curé to head a ceremonial procession round the woods where the sugar maple grew, sprinkling the trees on the way with holy water, reciting liturgies, and praying that there might be a good crop of sugar and syrup.

‘People nowadays call that superstition,’ says Suzor-Coté. ‘But there is something big in the idea. It links up daily works and divine; it is a recognition of a Power that is greater than man, a recognition of the Source of All. Such a ceremony is ennobling and reverential. It is big, and it makes me feel. And when I feel, then I can paint. That is the great thing — to have a feeling. And always when I am in my own country, and among my own people, I have feeling and inspiration.’

The large artwork, exhibited in 1920 and now owned by the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (1934.13), was painted by Suzor-Coté in close collaboration with his pupil, Rodolphe Duguay, as the latter mentioned in his journal1.

This sketch is one of the many studies that Suzor-Coté created prior to painting the massive historical composition, including a preparatory pastel work (private collection and oil study, MMFA). There are significant variations from the final painting, such as the absence of the altar boy carrying the stoup and the cross-bearer being pushed to the background. This first draft set the scene in a dense forest where the trees were already tapped, and buckets were hung to collect maple water. In the final version, the buckets are replaced by flat containers on the ground.

The dense crowd of parishioners meld with the maple grove’s dark background, which contrasts with the priest’s clothes, the light reflected on the tree trunks and the white snow, on which dropped shadows indicate that the ceremony was held early in the morning.

____________________________________________

Bien que la tradition de la bénédiction des érables ne soit pas bien documentée (Le Terroir, 11 mars 1919, p. 26-27), Cette coutume aurait été pratiquée en Estrie. Je n’ai pas trouvé de traces de cette cérémonie à Arthabaska où il se trouvait cependant plusieurs érablières. Suzor-Coté était très intéressé par ces forêts, nombreuses dans la région. Il a d’ailleurs représenté la cabane à sucre de Nathée Blanchette et celle qui se trouvait sur la ferme Edgewater, la propriété de son ami Harry Norton.

Suzor-Coté intitule son tableau au moment où il est exposé en novembre 1920 à la 42e exposition de la Royal Canadian Academy of Arts qui se tient l’Art Association of Montreal : La Bénédiction des érables, vieille coutume canadienne-française disparue. Le fait qu’il ajoute le mot disparue au titre suggère qu’il n’a pas été témoin de cette scène qu’il imagine avec tout son décorum.

En effet, le prêtre est vêtu d’une chape rutilante d’or et de broderie et il est accompagné d’un enfant de chœur et d’un homme portant une croix de procession. Il récite une prière afin que la Providence permette aux arbres de produire une sève généreuse qui sera transformée en sirop, en tire et en sucre d’érable.

Lintern Sibley commente dans The Year Book of Canadian Art 1913 cette composition alors en chantier dans l’atelier. Il rapporte le propos du peintre :

Nothing enthuses him [Suzor-Coté] like his own ancestral country and the old customs of his race — now, alas, falling, many of them, into disuse. At this writing, he is engaged in painting a huge picture depicting one of these of customs — the blessing of the maple sugar bush. It used to be the custom when the last snow disappearing for the curé to head a ceremonial procession round the woods where the sugar maple grew, sprinkling the trees on the way with holy water, reciting liturgies, and praying that there might be a good crop of sugar and syrup.

‘People nowadays call that superstition,’ says Suzor-Coté. ‘But there is something big in the idea. It links up daily works and divine; it is a recognition of a Power that is greater than man, a recognition of the Source of All. Such a ceremony is ennobling and reverential. It is big, and it makes me feel. And when I feel, then I can paint. That is the great thing — to have a feeling. And always when I am in my own country, and among my own people, I have feeling and inspiration.’

Le grand tableau exposé en 1920 et maintenant la propriété du Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (1934.13) a pas été peint par Suzor-Coté en étroite association avec son élève Rodolphe Duguay ainsi que celui-ci en témoigne dans son journal (1).

La présente ébauche fait partie des études que Suzor-Coté a réalisées en vue de cette imposante composition historique, dont un pastel préparatoire (coll. privée et une étude à l’huile, MBAM). Elle présente des différences importantes avec le résultat final, dont l’absence de l’enfant de chœur portant le bénitier et le fait que le porte-croix soit relégué au second plan. Il s’agit d’une première pensée qui campe la scène dans une forêt dense où les arbres sont déjà entaillés et auxquels on a accroché des seaux destinés à recueillir l’eau d’érable. Dans la version finale, ces seaux seront remplacés par des récipients plats posés à même le sol.

La foule compacte des paroissiens réunis fait corps avec le fond sombre de l’érablière. Elle contraste avec l’habit du prêtre, les éclats de lumière sur le tronc des arbres et le blanc de la neige marquée par les ombres portées qui indiquent que la cérémonie a lieu tôt en matinée.

(1) Rodolphe Duguay note dans son Journal à la date du 29 août 1920 : « Hier reçu une lettre de Suzor-Coté me disant de commencer un autre tableau, La Bénédiction des érables. J’ai commencé tout de suite hier a.m. à me mettre en train. »

La lettre de Suzor-Coté datée du 25 août précisait ceci : « […] dans ma pile de tableaux appuyés le long du mur, vous y trouverez ma grande photographie de La Bénédiction des Érables à sucre, vous mettrez au carreau et commencerez à ébaucher avec l’étude au pastel qui est sur le mur à droite au fond de l’atelier. Je voudrais bien que vous puissiez m’ébaucher ce tableau avant de partir pour la Ville Lumière. »

Le 5 septembre, Duguay écrit dans son Journal : « Hier midi, je finissais de tracer La Bénédiction des Érables. J’ai hâte de me sauver chez nous. »

Rodolphe Duguay Journal 1907-1927, Jean-Guy Dagenais, Claire Duguay, Richard Foisy éd., Montréal Les Éditons Varia, 2002, p. 100, 102.

Laurier Lacroix, «Rodolphe Duguay et Suzor-Coté», Liberté (231), vol. 39, n° 3, juin 1997, p. 103-119.

Laurier Lacroix