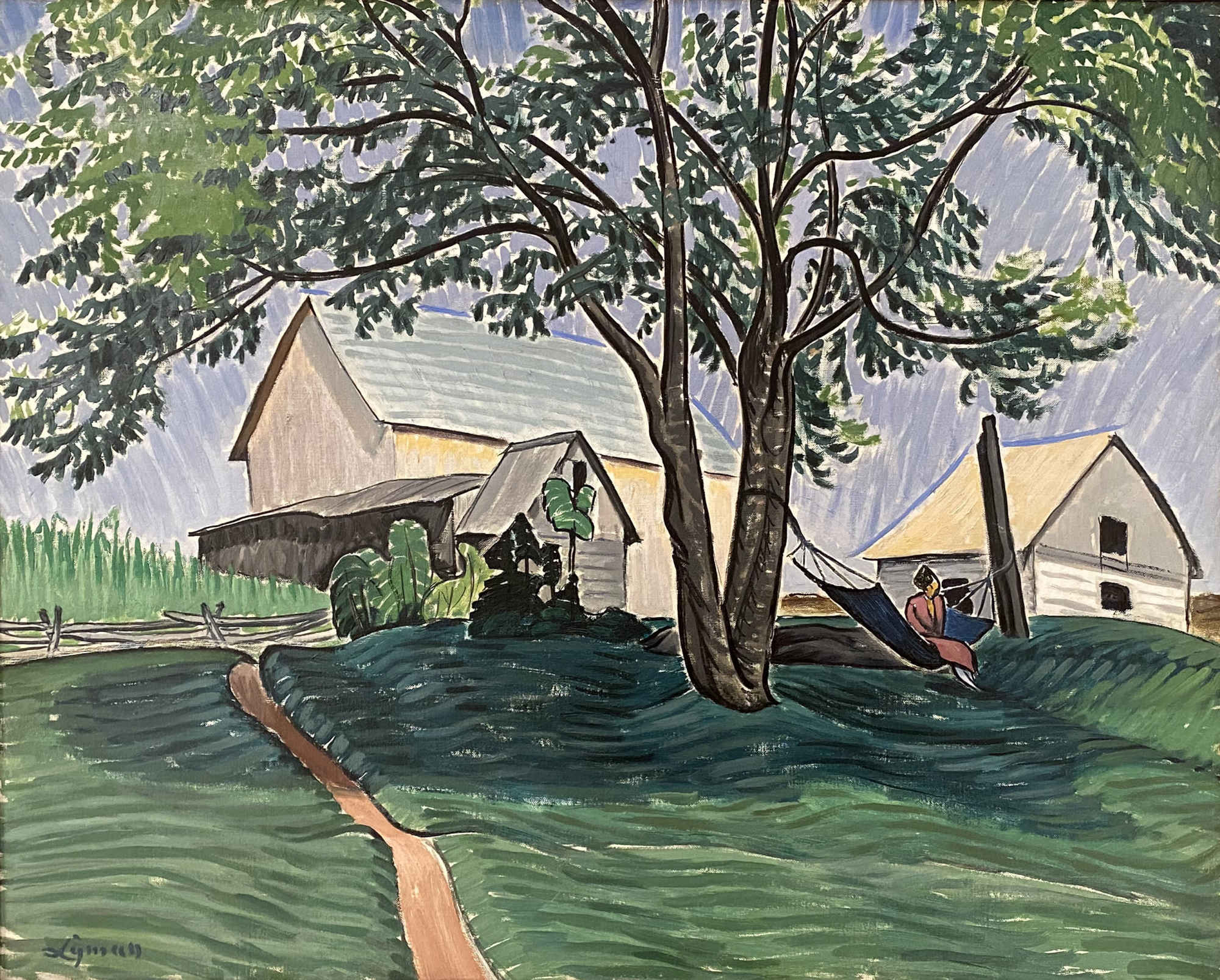

Notable Sales

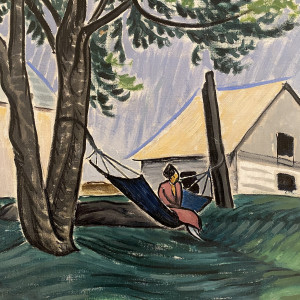

The Hammock Under the Tree (Dalesville, Quebec), 1912

61 x 76.2 cm

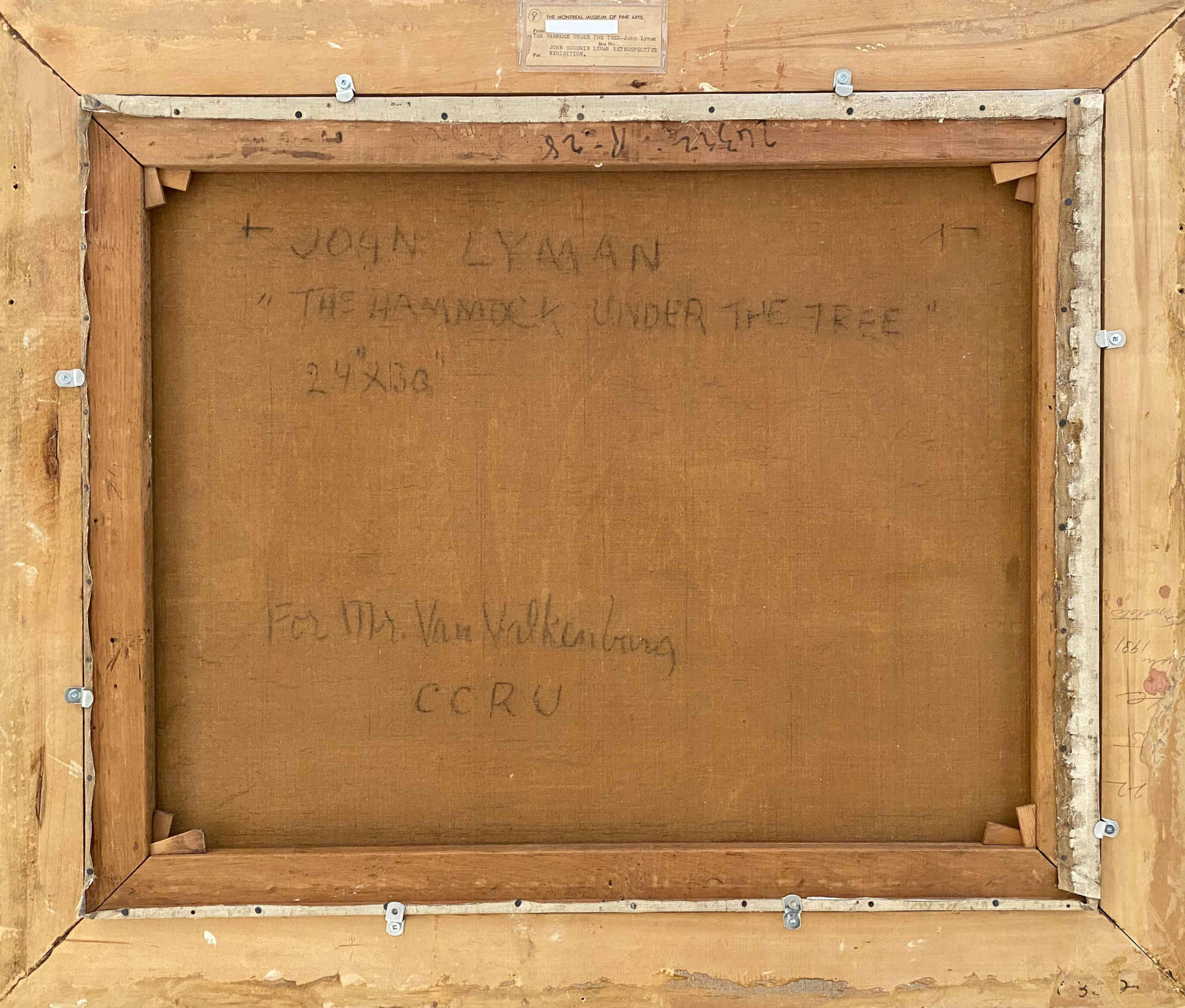

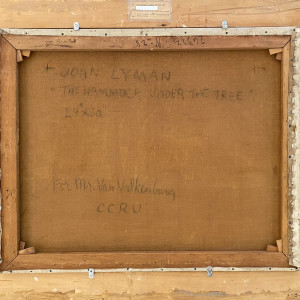

Inscriptions

signed, ‘Lyman’ (lower left); signed, titled and inscribed by the artist, ‘JOHN LYMAN / “THE HAMMOCK UNDER THE TREE” / For Mr. Van Valkenburg CCRU’ (verso)Provenance

Dominion Gallery, Montreal.

Richard S. Van Valkenburg, Toronto.

Private collection, Montreal;

By descent to the present owners.

Exhibitions

Montreal, Dominion Gallery, John Lyman and Louis Archambault, 23 April – 3 May 1947,

no. 3.

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, 9 - 11 Feb 1948, Vancouver, Vancouver Art Gallery, 17 - 19 Feb 1948, Winnipeg, Winnipeg Art Gallery, 20 - 23 Feb 1948, Toronto, Art Gallery of Toronto, 25 - 26 Feb 1948, Montreal, Art Association of Montreal, 27 - 29 Feb 1948, Canadian Appeal for Children, exhibition and auction organized by NGC and UNESCO.

Montreal, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 5 - 29 Sept 1963, Ottawa, The National Gallery of Canada, 4 - 27 Oct 1963, and Hamilton, The Art Gallery of Hamilton, 8 Nov - 1 Dec 1963, John Lyman, no. 8 as The Hammock Under the Tree.

Literature

John Lyman, Louis Archambault (exhibition leaflet), Montreal, Dominion Gallery [1947] no. 3.

Travelling Exhibition & Auction of Canadian Paintings & Sculpture, Canadian Appeal For Children (typed list), Library, National Gallery of Canada, one page.

Anon, “Art Exhibit to Assist Children of Europe”, The Evening Citizen (Ottawa, ON), 10 February, 1948, p. 3, reproduced b/w.

Anon, “Travelling Art Show Makes Novel Appeal”, Montreal Standard (Montreal, QB), February 28, 1948, mention.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, John Lyman, 1963, no. 8 as The Hammock Under the Tree, repr. (unpaginated)

Evan H. Turner, Gilles Corbeil, John Goodwin Lyman Retrospective (Exhibition catalogue), Montreal, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1963, np, cat. 8.

Louise Dompierre, John Lyman, 1886-1967, Kingston, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1986, p. 206 and 209.

Returning to Montreal at the end of 1910, Lyman became engaged to Corinne St. Pierre—daughter of the well-known tailor William St. Pierre—and they married in the spring of 1911. Before setting off for Europe, the couple paid a visit to 291, the famous avant-garde art gallery in New York City, where they discovered the articles on Matisse and Picasso written by Gertrude Stein in the photographic journal Camera Work, edited by Alfred Stieglitz. Once they were in Paris, in early June, John and Corinne met Matisse at the Salon des Indépendants, then visited Gertrude Stein, since John had been a regular figure at her salon in his student days. In 1911, Corinne became pregnant and gave birth to a child who died a few days later. In the summer of 1912, the Lymans settled in the hamlet of Dalesville, in the Argenteuil region located between Montreal and Ottawa. Dalesville was part of the rural area near the town of Lachute where, since the 19th century, Anglo-protestant Scottish and Irish merchants and farmers would vacation. The region inspired the painter to create landscapes—paintings which caused a scandal in May 1913 at the Art Association of Montreal. It must be said, Lyman’s modernist paintings had already earned scathing criticism at the 1912 and 1913 Spring Exhibitions, but this time, the invectives reached their pinnacle. He publicly defended his avant-garde approach, which had been clearly explained by Corinne St. Pierre who had penned the preface for the exhibition’s catalogue, before resigning himself to exile. It was only eighteen years later, in 1931, when the couple returned to settle permanently in Canada. It was then that the painter found a community that was more open to modern art. He brought together young artists in groups like the Atelier, the Eastern Group and the Contemporary Arts Society. As a painter, art critic and McGill University professor, he dedicated himself entirely to defending art that strives for universality. John Lyman passed away in 1967 in Barbados at the age of 71, followed a few months later by his wife Corinne.

Lyman’s 1913 one-man show, a landmark event in Canadian art history, has yet to reveal all its mysteries: of the 35 works (paintings and drawings) presented—among the 42 listed in the catalogue—few have reached us. At the time, Lyman favoured evocative rather than descriptive titles, often relating to music, which creates another obstacle to retracing these works. Fortunately, the images reproduced in newspapers and a few brief descriptions from the critics (hidden amongst the insults) provide some leads. For example, Wild Nature Impromptu, 1st State, a landscape painted in Dalesville in 1912 (no. 36 in the 1913 catalogue), is in the collection at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (1970.499), a gift of the Mrs. John Lyman’s Estate in 1970. Dalesville, another similarly sized landscape painted that same year, is also part of the collection (1970.500). But what became of Rural Sensation (no. 35) or Canadian Essay, No. 2 and No. 3 (no. 26 and no. 34) from the 1912 catalogue?

After the disastrous exhibition, the artist kept the works from this time period for himself. Some resurfaced three decades later in retrospective exhibitions held at the Dominion Gallery in 1944 and 1947 [3]. It was during the second exhibition, which featured works by both Lyman and the sculptor Louis Archambault, that the astounding painting The Hammock under the Tree was presented to the public for the first time. The following year, the painting was included in the exhibition and sale organized by the Canadian Council for Reconstruction through UNESCO (CCRU), coordinated by Richard S. Van Valkenburg, director of Eaton’s Fine Art Gallery and a prominent figure of the Toronto art scene. This explains the verso inscriptions on the painting.

This exhibition was part of the large scale charity campaign, Canadian Appeal for Children, in which 46 countries of the United Nations contributed to the cause for children of the Second World War. In Canada, every sector of the economy was called upon. The exhibition was placed under the authority of the Canadian Art Council. Thirty-five painters and five sculptors answered the request from Montrealer Marian D. Scott and Torontonian Charles F. Comfort, who headed the CAC member committee. Travelling to five major Canadian cities in February 1948, the exhibition featured a range of styles of recent contemporary Canadian art, from realism to abstraction [4]. In this regard, John Lyman was unique, choosing to exhibit a work he had painted over 35 years earlier, The Hammock under the Tree [5]. It was during this exhibition that the painting was acquired by the family of the present owners - a collector known for his interest in modern art and the works of James W. Morrice in particular [6].

Ever since he had studied in Paris, John Lyman had been a great admirer of Morrice. When Lyman returned to Canada, he wrote a monograph about Morrice, which was published in 1945 by Éditions de L’Arbre in Montreal. The two Canadians, who had both known and frequently visited with Henri Matisse, shared the great Fauvist’s view of art; Namely, that art should express feelings rather than transpose reality. This is precisely what Corinne St. Pierre had tried to explain to the Montreal public in the preface for her husband’s exhibition catalogue in 1913: “Art that looks natural is nonsense; art must be artificial; where imitation ceases, art begins; […] Art is not the story of what we see, but of what we think about what we see; what determines it is what arises between expression and the inspiring object: imagination, organizing intelligence and personality as well.” [7]

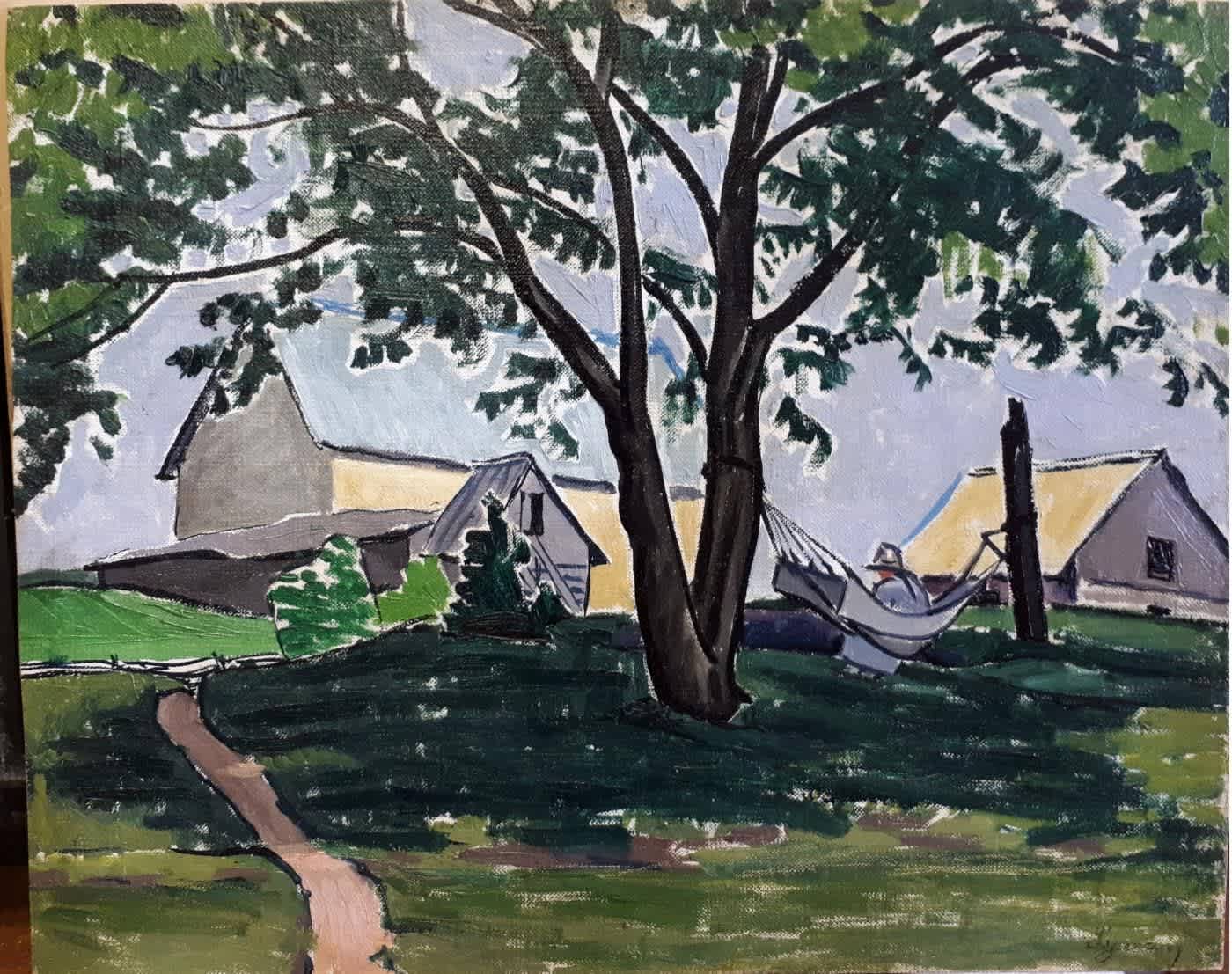

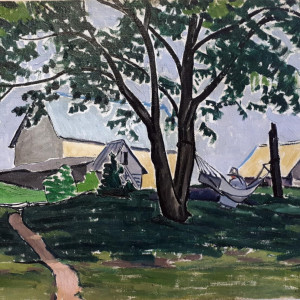

The late François-Marc Gagnon wrote that, in the development of Canadian art, Morrice and Lyman were, “‘the missing link’ of Fauvism, between the Impressionism of Clarence Gagnon, the early-twentieth-century painter bitterly opposed to everything that had followed Impressionism, and the Cubism of Alfred Pellan, who had spent fourteen years in Paris in contact with all the avant-gardes.”[8] The exhibition Morrice and Lyman in the Company of Matisse, organized by the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in 2014, demonstrated their aesthetic kinship. Certainly, The Hammock under the Tree could have been included in the exhibition for its decorative qualities. But the work escaped attention, tucked away in the current collection, having emerged just once in 67 years, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ retrospective exhibition of Lyman’s work in 1963. The exhibition also toured to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. Interestingly, the latter gallery recently acquired the sketch for this work (Fig. 1).

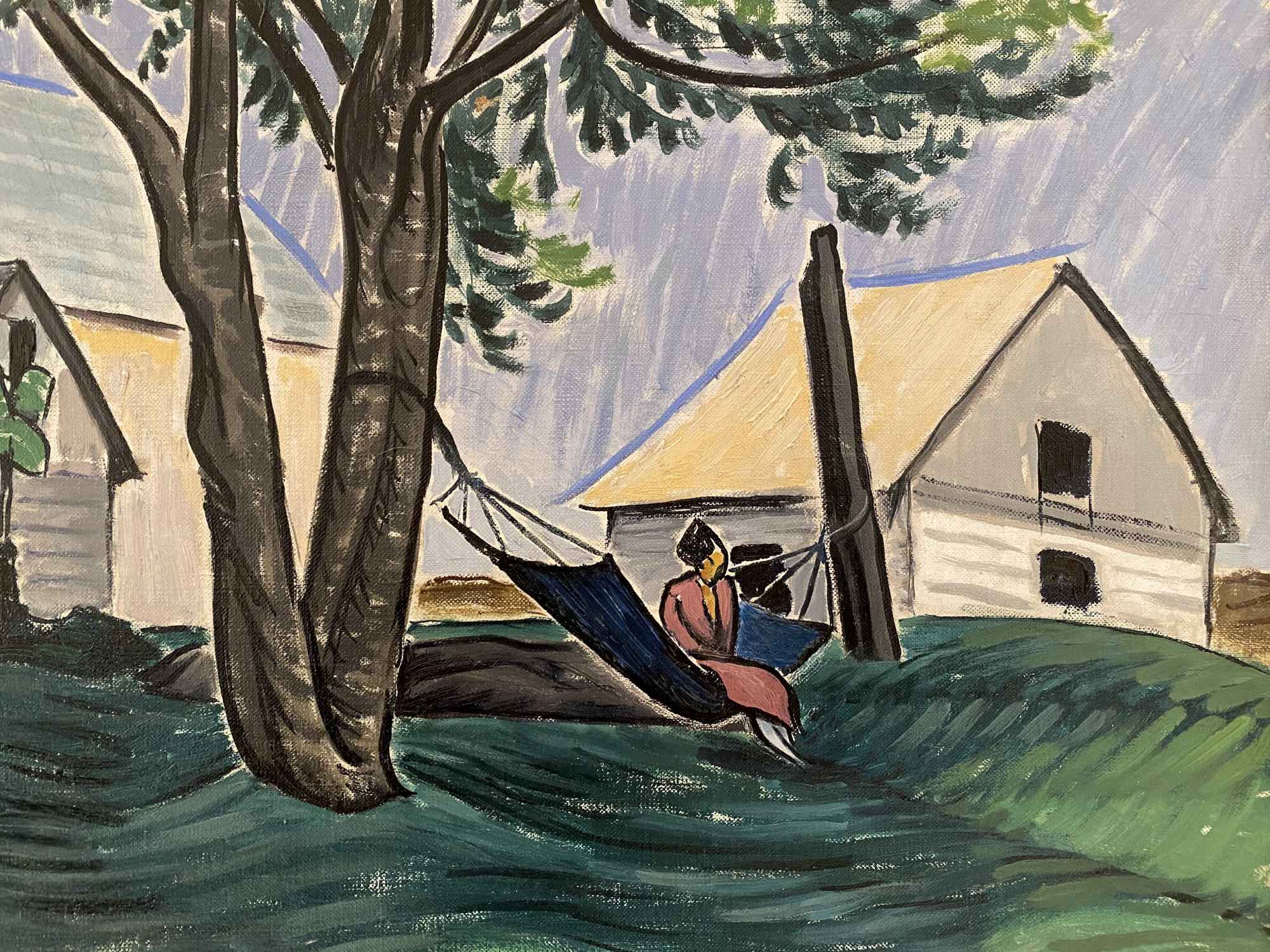

John Lyman adopted the artistic principles championed by Henri Matisse as displayed in The Hammock under the Tree. The meticulous composition of the elements seen in the study were reproduced in the large painting. A notable difference is the pink clothing worn by the female figure—most likely Corinne, now facing forwards. It becomes a focal point from which a multitude of chromatic waves flow through the areas of light and shadow. The long brushstrokes of colour and areas of exposed canvas bring movement to the painting, from left to right and from bottom to top. Devoid of any picturesque elements, the landscape respects the two-dimensional plane by highlighting the foreground and background elements and using yellow gold for the structures. The motifs of the shrubs to the right of the dirt path as well as the woman are reminiscent of the dark outlines and shading used in other Dalesville scenes.

There are few examples where John Lyman pushes the pictorial and decorative treatment of surfaces so far [9]. Just as in a musical composition, here, the smallest element contributes to the overall dynamic of the piece: the rhythmic sensations evoke the wind that sweeps over the waving grass and rustles the leaves of the umbrella tree. On this beautiful summer day in the country, these waves carry through into the sky, fanning out into sunbeams. The Hammock under the Tree embodies what Lyman meant when he said that “the painter’s job is to persuade nature to collaborate with him.” This remarkable work illustrates John Lyman’s unique early contribution, at a time when the art world was vehemently averse to the new languages of the Parisian avant-garde. [10]

Michèle Grandbois

_________________________________

Footnotes:

1. This text greatly benefited from the assistance of Annie Arsenault (National Gallery of Canada) and Danielle Blanchette (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) and fruitful discussions between the author and Lucie Dorais, Charles C. Hill, Tobi Bruce (Art Gallery of Hamilton) and Nathalie Thibault (Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). I would like to extend my warm thanks to them all.

2. Guy Viau, “John Lyman,” Montreal, Vie des arts (33), Winter 1963–1964, p. 30.

3. Charles Hill found the consignment record for The Hammock under the Tree in the archives of the Dominion Gallery, May 17, 1946, stock no. 12120d.

4. Although she had passed away in 1945, Emily Carr was among the 40 artists whose works were included in the exhibition. Her estate donated her later painting The Wood. Other artists featured in the exhibition included painters Franklin Arbuckle, Archibald Barnes, Allan Barr, P. E. Borduas, Fritz Brandtner, A. J. Casson, Paraskeva Clark, Charles F. Comfort, Stanley Cosgrove, Jacques De Tonnancour, Kenneth Forbes, Eric Goldberg, Lawren Harris, Edwin H. Holgate, A. Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, Henri Masson, David Milne, Lilias Torrence Newton, Louis Muhlstock, Jack Nichols, Will Ogilvie, Alfred Pellan, Robert Pilot, Goodridge Roberts, Anne Savage, Carl Schaefer, Marian D. Scott, Percy Tacon, Frederick H. Varley, R. York Wilson, William A. Winter; and sculptors Emanuel Hahn, Jacobine Jones, Stephen Tranka, Florence Wyle and Elizabeth Wyn Wood.

5. The work’s record at the Dominion Gallery lists the completion date as “September 1912.”

6. [Names withheld]

7. Foreword to the Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by John G. Lyman, presented at the AAM from May 21 to May 31, 1913 in Morrice and Lyman in the Company of Matisse, p. 223.

8. “Lyman’s Encounter with Matisse” in Morrice and Lyman in the Company of Matisse, (exhibition catalogue), Richmond Hill, Kleinburg, Québec, Firefly Books, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, 2014, p. 171.

9. On the Beach, Bermuda, 1913 (Lavalin Collection of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal A 92 995 P 1) and The Lawns of Fairfield, Cowansville (Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, gift of Mrs. John Lyman Estate [1970.510]).

10. To our knowledge, John Lyman revisited the hammock as a subject in 1926, in a work that was displayed at the Salon des Tuileries in Paris in 1927 before being presented, that same year, in the artist’s first exhibition since 1920 in Montreal at Johnson Art Galleries Ltd. (634 St. Catherine Street). The Hammock, oil on wood, 30 x 40 cm, is now housed at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, gift of Mrs. John Lyman Estate (1970.506).