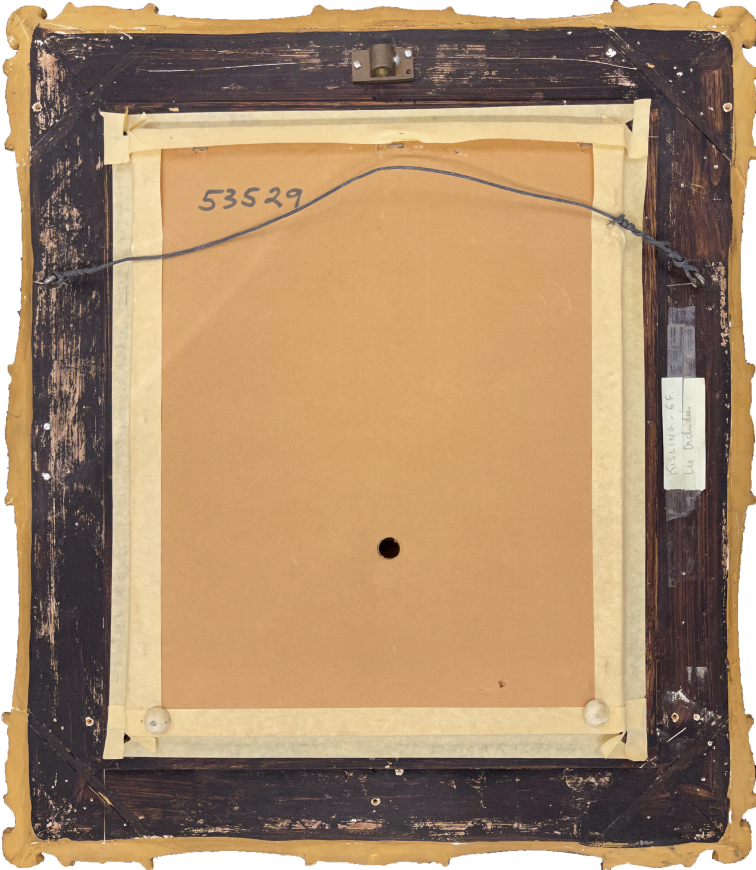

41 x 33 cm

This work is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from Jean Kisling, dated March 19, 1974. Kisling is the co-author of the 'Catalogue Raisonné de l’Oeuvre de Moïse Kisling' currently being prepared with Marc Ottavi.

Inscriptions

signed, 'Kisling' (lower left)Provenance

Wally Findlay Galleries, March 1975

Acquired from the above by the present private collection, Montreal, March 1975

Documentation

Moïse Kisling et al., Kisling (New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 197“Poland has long been the merging ground of Western Slavonic cultures. Through the centuries of struggle, conquest, independence and reconquest, Poland has been a crossroads for both invading armies and currents of thought and culture from the west and the east. From the point of view of art, the French influence has been especially strong on a number of artists. This was particularly so in the case of Kisling.

Moïse Kisling was born in Cracow, Poland on January 2, 1891. At the time of his birth, Cracow was actually in Austrian territory, and thus it is not surprising that the art of Kisling’s native city was dominated by Austrian art.

Kisling’s father was a tailor, but there was no question of having Moïse follow in this father’s footsteps. From earliest childhood his gift for drawing was evident, and the family therefore planned to have him become an engineer, but at the age of fifteen he won a competitive art examination and as a result entered the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts. There he would normally have been subjected to Germanic influences, but his professor at the academy was Josef Pankiewicz who had resided in France and knew the Impressionists, Bonnard and Vuillard, and carried back to Poland the new vision and impetus of Impressionism.

After four years of study under Pankiewicz and with his encouragement, Kisling went to Paris and settled in Montparnasse. He lived in an attic in the Rue des Beaux-Art near St-Germain-des-Prés. His wit, joviality, talent and charming, sensitive nature rapidly gained many friends for him. Very soon he was accepted as an intimate of the group at the Café de Versailles, where Guillaume Apollinaire, Picasso, Derain, Modigliani, Pascin and André Salmon met, and where the Ecole de Paris was born. Gay and generous, Kisling enjoyed life in Paris and was soon recognized as one of the most likeable and picturesque figures of the quarter in which he lived. His gaiety sometimes turned into boisterousness; twice he was involved in duels.

After Kisling had been in Paris a short time, he made a trip to England. Upon his return to France, he followed Picasso to Céret, the Barbizon of Cubism. There he became closely associated with Braque and Juan Gris, as well as the poet, Max Jacob, and Frank Haviland, the manufacturer of Limoges, who was an admirer and collector of Picasso’s work. Like the painters Modigliani, Pascin and Soutine, Kisling was aware of the revolution Cubism was effecting in art, and his awareness is manifest in some of his portraits and landscapes of his period, yet he developed his own personal style of expression. He painted landscapes in which the influence of Cézanne is clearly evident, but among artists of his own time it was Derain who influenced his work most strongly. From Derain he gained in particular the typically French sense of proportion and, for a time at least, his native sensual exuberance was somewhat repressed in his paintings. The fire of his natural temperament, however, was not dimmed as is proved by the fact that in 1912 he fought a furious duel with sabers and pistols with his compatriot Leopold Gottlieb.

In 1914 Kisling returned to Paris and took a studio in Rue Joseph-Barrat. Modigliani often came to Kisling’s studio to paint and to sleep. When the First World War broke out, Kisling was travelling in Holland. He immediately returned to Paris and enlisted in the Foreign Legion. In the trenches his closest companion was Blaise Cendrars. In 1915, Kisling was wounded in action and subsequently released from service.

With Kisling’s return to civilian life, a new phase in his career as an artist began. Four years after his release from military service, he had a Parisian exhibition. Though he had exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants in 1913, before his Paris exhibition of 1919 his paintings had been known and appreciated by only a restricted circle of fellow artists. The Paris exhibition of 1919 was an outstanding success and brought him both recognition and acclaim.

Kisling was twenty-eight years old. He had freed himself completely from Cézanne and developed his own personal and distinctive style in which the spirited use of color springing from his native tradition was combined with the discipline acquired through his years of contact with French painters. From that point on, his fame became worldwide. He was, and is, acknowledged as one of the best painters of the Ecole de Paris and is now represented in important museums and private collections throughout the entire world. Kisling’s work is in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, and in the museums of Belgrade, Brooklyn, Lisbon, Los Angeles, Marseille, Moscow, Stockholm, Tel Aviv and Venice.

Two other events marked 1919 as an important year in Kisling’s life. He became a French citizen, and the Order of the Legion of Honor was conferred upon him. The following years were filled with intense work and with success. A series of exhibitions in Paris was followed by exhibitions in New York, London, Geneva, Brussels, all of them adding to his fame. In 1926 he went to paint at La Ciotat, Sanary, near Saint-Tropez, and was so delighted with the area that he later built a home there.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Kisling volunteered for the French Army, at the age of forty-eight. But France fell, and Kisling was threatened by the Gestapo, so he made his way to Portugal and then to the United States. He had always liked to paint artists and actresses: Michele Morgan, Arletty, Edith Mera, Madeleine Sologne had sat for him in France. In the United States Chaplin, Charles Boyer, Paulette Goddard, Arthur Rubinstein and Edward Robinson came to his studio.

In 1946, Kisling returned to France and was reunited with his two sons, one of whom had been a fighter pilot in the Free French Air Forces. He settled in Sanary-sur-Mer in Provence, and died there in his villa in 1953 after a brief illness. He was then sixty-two years old. He had been painting for forty-seven years and in that time had produced landscapes, still lifes, figure paintings and portraits, in all of which the magnificence of his brilliant coloring, his strong sense of form and composition are the silent yet living proof of his genius.

Kisling was one of Modigliani’s closest friends. He was faithful to that star-crossed genius until the latter’s death in 1920. In some of Kisling’s paintings of female nudes and of young boys there are traces of the melancholy so characteristic of Modigliani, but Kisling’s masterly use of pulsating color lends a note of joy even to these canvases.

In ‘Modern French Painters’ Jan Gordon speaks of the use of color in terms which apply perfectly to the work of Moïse Kisling. He says: ‘By color one does not imply that actual color must be forced to any exaggerated pitch of garishness. Color covers every kind of tint, and every shade of grey. But intelligent color realizes both the value of the most forceful as well as the most subtle of notes. The colorist organizes design as carefully as he organizes his linear or spatial construction. He uses color as it is necessary to the emotional intention of his work.’

Though Kisling had lived most of his life in France, had fought for France, and was a French citizen, he never forgot or lost the riches of his Slavonic heritage. Byzantine art touched the Slavonic nations and gave them a hieratic sense of form and a love of brilliant color. Kisling used color, in the words of Jan Gordon, ‘as it is necessary to the emotional intention of his work.’”