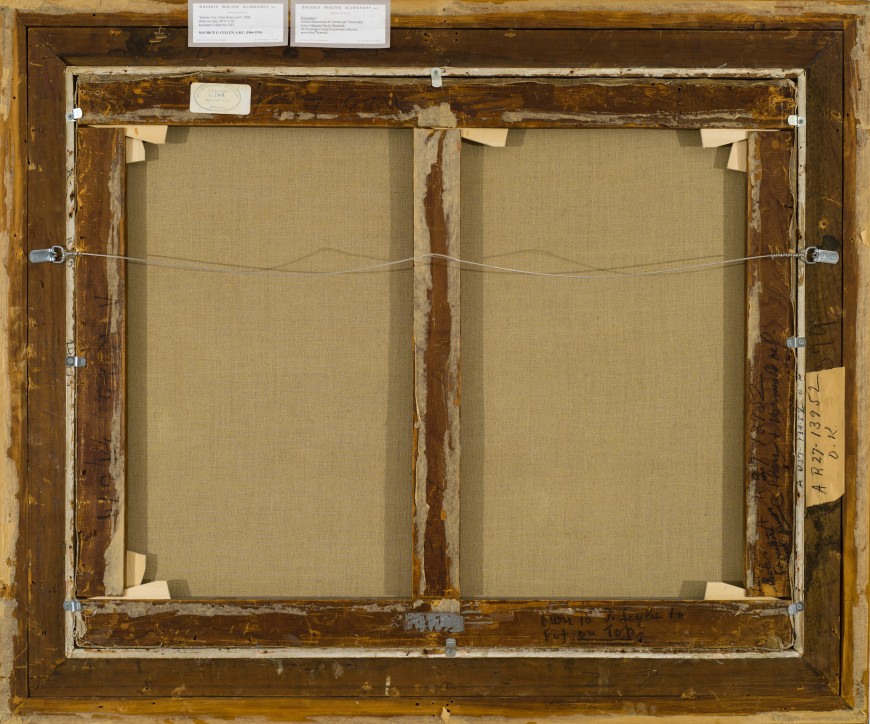

73 x 91.4 cm

Alan Klinkhoff Gallery Cullen Inventory No. AK1307.

Walter Klinkhoff Gallery Cullen Inventory No. 1307.

Inscriptions

signed and dated, ‘M Cullen/ 04’ (lower right)Provenance

Purchased from the artist by the Honourable Louis-Athanase David, Montreal

Mme Simone David Raymond, Montreal, daughter of The Honourable Louis-Athanase David

Heffel Fine Art Auction House, Fine Canadian Art, 25 November 2006, lot 20

Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc., Montreal

Property of a Distinguished Montreal Collector

Documentation

Power Financial Corporation, Annual Report 2007, p.36-37 [reproduced].

Alan Klinkhoff was introduced to this extraordinary Maurice Cullen in 1985 at the home of Mme. Simone Raymond, a daughter of The Honorable Athanase David. Athanase David has been referred to as “Le parrain de la culture au Québec”, The Godfather of Culture in Quebec. [1]

According to Mme Raymond, many artists of the day, including Maurice Cullen, Clarence Gagnon, Horatio Walker and Suzor-Coté were friends of the family. Some of them had attended her wedding, she recalled. Québec, Vue de Lévis had been in the extended David family for 3 generations, until 2006 when we purchased the painting for a distinguished Montreal collector.

Under Quebec’s Prime Minister Taschereau, The Honorable Athanase David's mandates and responsibilities were formidable, touching a wide variety of life in Quebec. Among them was the establishment of the Quebec Museum,the legacy of le Musée National des beaux-arts du Québec. David began to purchase paintings fully two years before the museum was officially created, beginning with the purchase of a painting each by Maurice Cullen, Albert Robinson, Suzor-Coté, Clarence Gagnon, and Alice Des Clayes.

A.Y. Jackson wrote about Cullen and his influence on the Group of Seven, “To us he was a hero. His paintings of Quebec City from Lévis and along the river are among the most distinguished works produced in Canada, but they brought him little recognition.”[2]

______________________

Footnotes:

[1] Radio-Canada, 'Athanase David, le parrain de la culture au Québec,' Radio-Canada.ca, accessed November 16, 2023,

[2] A.Y. Jackson, A painter's country: The autobiography of A. Y. Jackson (Vancouver/Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited, 1958), 19.

Maurice Cullen, Québec City View from Lévis

by Jocelyn Anderson

By 1904, Maurice Cullen had become well-known in Canadian art circles for his Quebec landscapes. He specialized in rural scenes, but he also depicted Quebec City, and Québec City View from Lévis likely dates from January 1904, when he visited Lévis to work on several paintings. [1] In this composition, two trees heavily laden with snow dominate the foreground, and late afternoon sun casts their shadows, pale blue lines stretched across the frozen earth. The city itself is a distant silhouette on the horizon, with only a few of its towers and buildings on the waterfront appearing distinctly. Ice patches on the river contrast with the water, drawing attention to the movements of currents in the freezing weather. Above, the sky shifts from pale grey to bright blue.

Cullen was one of many to depict Quebec from Lévis, which, situated on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, offered a picturesque view of the city across the water. The location had been popular with artists since the 1700s, when watercolourists such as James Peachey (died 1797) and George Heriot (1759–1839) worked there; in the nineteenth century, some of the most successful painters in Canada went there, including Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872) and Lucius O’Brien (1832–1899), as well as many photographers, among them Alexander Henderson (1831–1913), William Notman (1826–1891), and Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905). Cullen’s Québec City View from Lévis is one of several he did at Lévis; of particular relevance to this painting is one of the same name, also from 1904, that is in the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. It presents a slightly different scene: it does not include the trees in the foreground, situating the viewer closer to the river, such that the water and ice fill the lower third of the composition and the buildings and towers of the distant city have greater definition.

The vast river scene in winter was the ideal subject for exploring a wide range of effects of light on snow and ice, an interest Cullen maintained for over thirty years. In his words, “Snow colours reflect the tonalities of the sky and the sun. They turn blue, mauve, grey and even black but never into pure paper white. Pure white can therefore only be applied locally. Snow, like water, reflects the interplay and the changes of light in the atmosphere. But whereas a water surface may appear like a combination of countless tiny mirrors, snow shows fewer sides to light. At dusk when the sun is warm and sits on the horizon, the snow appears red. The shadow of a cloud or a mountain also produces astonishing colours. When rivers come back to life in early spring, water rises above the ice and spreads slowly, contrasting in darkest blue, almost black, with the surrounding snow. One has to look carefully and conscientiously and be patient.”[2]

As Robert Pilot (1898–1967), Cullen’s stepson, noted, this profound understanding of how snow, ice, and water responded to light was the result of years of work which began in the mid 1890s and became a major focus around the turn of the century when the artist “commenced a searching and prolonged study of the light on snow, and worked winter after winter out of doors […] He built up from these years of sincere study a knowledge of the light on snow, with its intricate laws of complementary colour and of reflected tone which has been surpassed by none.” [3] Cullen’s decision to focus on the effects of light on snow may also have been driven by his interest in the Impressionist movement and how its leading artists had experimented with the representation of light.

Regardless of how inspiring a winter landscape was in formal terms, it could also be a controversial subject. Surveying the artist’s work in 1912, Newton MacTavish credited Cullen with being one of few artists to take up winter as his focus, noting that at the turn of the century, winter was not widely embraced as an appropriate season to depict the Canadian landscape: “for years Mr. Cullen has rendered snow upon canvas studiously and consistently, until now we regard him as the interpreter par excellence of what is pre-eminently a glorious contribution to the Canadian winter. And he has carried on this work in spite of popular and official prejudice against it, because it is a singular notion among persons in high positions in Canada that the Canadian winter season is something of which the rest of the world should be kept in ignorance.” [18] At the time that Québec City View from Lévis was painted, many Canadian leaders believed that celebrating winter in Canada risked deterring immigrants and, by extension, would be detrimental to national growth. Eventually, however, winter came to be seen as one of Canada’s defining attributes, and paintings like this one were admired for their nationalist undertones. Jocelyn Anderson

Jocelyn Anderson is the Deputy Director of the Art Canada Institute. Her research focuses on Canadian art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and more broadly on landscape imagery in the British Empire. She is the author of William Brymner: Life & Work, as well as essays for a number of periodicals including >British Art Studies and the Oxford Art Journal. She holds a PhD from the University of London (Courtauld Institute of Art).

______________________

Footnotes:

[1] “Current Art Notes,” Montreal Daily Star, January 9, 1904, 19.

[2] Mela Constantinidi and Helen Duffy, The Laurentians: Painters in a Landscape (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1977), 39.

[3]Art Gallery of Ontario Archives, “Maurice Cullen RCA, by R.W. Pilot M.B.E. RCA Address given at the Arts Club of Montreal, 1937,” 4.

[4] Newton MacTavish, “Maurice Cullen: A Painter of the Snow,” Canadian Magazine 28, no. 6 (April 1912): 537.