Ventes notoires

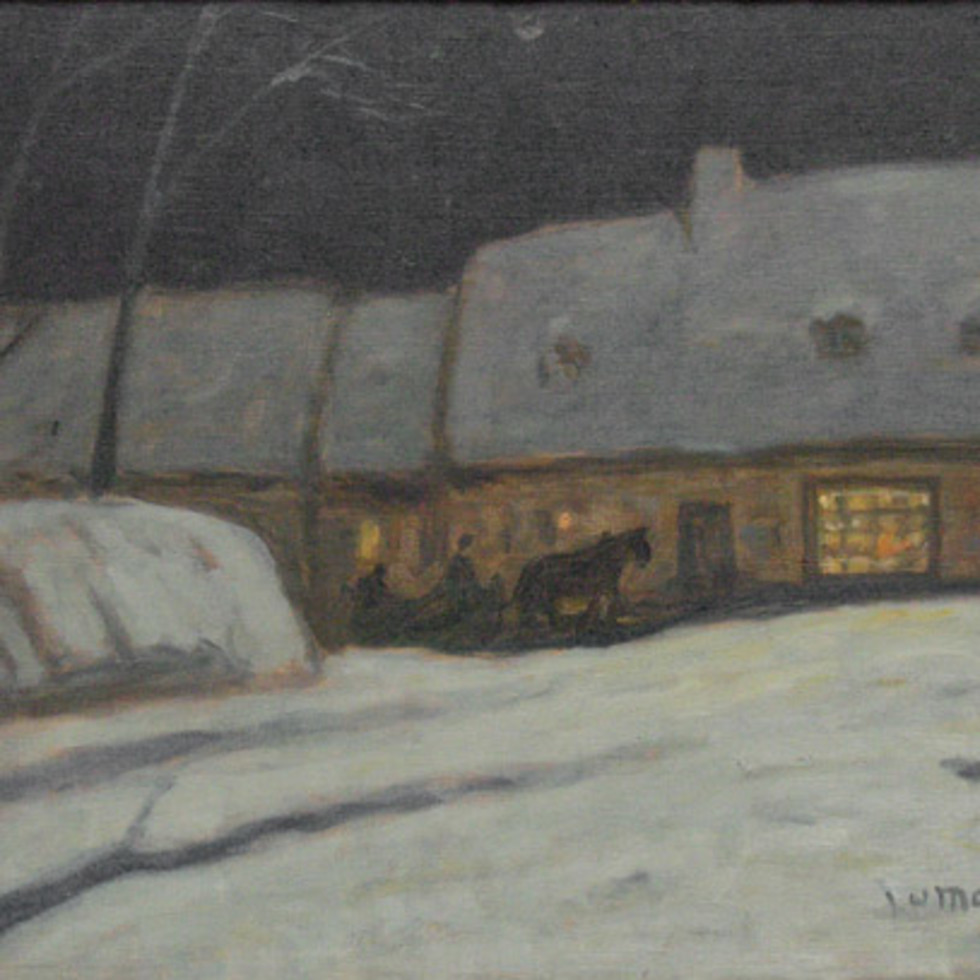

The Barber Shop, Montreal (Effet de neige, boutique), 1906

50.8 x 61 cm

This work will be included in the James Wilson Morrice Catalogue Raisonné being compiled by Lucie Dorais.

Provenance

Charles James Côté, Montreal, for Sir Charles Blair Gordon, Montreal (before 1925).

Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc., Montreal;

Acquired from the above by Mitzi and Mel Dobrin, Winter 1972-73.

Expositions

Paris, Grand Palais, Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Salon de 1906, 15 April - June 30, no. 915 as Effet de neige (boutique).

Mannheim, Internationale Kunst-und Grosse Gartenbau-Ausstellung (International Horticultural and Fine Arts Exhibition commemorating the 300th anniversary of the foundation of the city), May 1 - October 20, 1907, no. 582e as Haus des Barbiers.

Barber Shop debuted at the annual Salon de la Société Nationale in Paris in April 1906, one of four Effets de neige (sub-titled Montréal, Québec, boutique and traîneau) based on drawings and sketches executed the previous winter; it was the first time that the artist sent only Canadian subjects to a major exhibition. His visit, from Christmas 1905 to late February 1906, happened just after the Salon d’Automne where Matisse and his friends, Les Fauves, attracted most of the attention. Morrice’s four pochades at that Salon were hardly noticed, while six months before his contribution to the Nationale, six European subjects, were mentioned, and sometimes highly praised, in at least 75 reviews; the French Government had even bought a second painting from him (now lost). That Morrice had a sort of plan is evidenced by the large number of drawings and pochades he brought back to Paris, which will inspire him for a few years. The four sketches used in 1906 are still extant – the fourth one, that for Montreal, was discovered by Alan Klinkhoff only two years ago.

Morrice first drew the late Victorian shop with great care and details, including the barber post, the fire hydrant, and the sign of the shop next door, but no figures yet (fig. 1). The colours were noted on a wood panel with a limited palette of black, white, red and yellow; the composition is the same, plus a woman in black on the left; big, lazy snowflakes started to fall. In spite of its small size, the pochade is so complete that Morrice signed it (present location unknown, study based on a 1965 slide, National Gallery of Canada Archives).

The canvas is a study in subtle refinement: even if Morrice’s brushstrokes are thinner than before, he still applies them layer upon layer, in a slow addition process, on a canvas primed in turquoise for the brick areas, and a darker shade for the shop facade. The shop window occupies the centre third of the composition, and its paint surface was scraped to imitate glass panes. Comparison with the 1906 glass negative shows that Morrice continued to work on the window after the photo was taken, straightening all its lines even more with turquoise touches, and more scraping. The reworking continued after the framing: the pure white of the snow in the street was entirely covered by a thin layer of a delicate cream, then more turquoise for the shadows. One oversighted red line on the barber post was also corrected.

Morrice’s “Canadian offensive” at the Société Nationale was a mixed success, although he sold two paintings: Traîneau to the Musée de Lyon, and Québec to a European collector (now Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario). Perhaps eager to find the latest Fauve manifestation, French reviewers walked rapidly in front of the Canadian’s vues de neige (if at all: we found only 20 reviews in Paris); only a few stopped long enough to note their refinement, subtle harmonies, or the melancholy of their ciels mourants. But foreign correspondents did notice the new subject: the London Pall Mall Gazette (anon., 23 April) nicknamed Morrice Our Lady of the Snows, while the Philadelphia Inquirer (anon., 29 April) emphasized his “strikingly fresh, vigorous note amongst the surrounding imbecility... best of all, a line of shop windows blurred in the whirling snowstorm..." Finally, Morrice’s friend Elizabeth R. Pennell, writing as N.N. in The Nation (New York, June) saluted his “courage to seek new motives under new conditions, and to study them for himself under these conditions, instead of adapting them to a wellworn recipe.”

Whistler’s name was often mentioned by the French reviewers, especially for Barber Shop, this “boutique très whistlérienne” (Roger Marx, Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, 14 April), a “delicious, crepuscular harmony in white, grey and salmon of a snowy street” (Paul Jamot, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, June; our translation). James McNeill Whistler left us many small pochades and etchings of shop windows at night, mostly from the Chelsea part of London where he lived. If Morrice’s works show a strong Whistler influence before his discovery of Impressionism, some Venetian facades on the Grand Canal at sunset (1901-02), and of course Barber Shop, show that the spell still operated. In March 1905, as he wrote to Clive Bell, he was desperately trying to finish his Salon paintings in time to visit the huge Whistler Memorial Exhibition in London.

Whistler rarely named or located his little Chelsea Shops, and Morrice’s Effets de Neige are also anonymous, although we know the settings for Montréal (Place Jacques-Cartier) and Québec (Mountain Hill); Traîneau is a more generic winter scene. An old inscription on the back of Boutique/Barber Shop mentions Place Viger, but the square is flat, and there were no barber shops in eastern Old Montreal. A thorough study of 1906 street and business directories, coupled with virtual (and some real) walking, has not yet solved the puzzle, although the shop of G.A. Lafortune, at 65 Saint-Sulpice just below Notre-Dame Street, is a tantalizing guess: the street side and inclination are right, and the stone fence around Notre-Dame church offered a welcome seat.

Unfortunately, no contemporary photos exist, and the building was demolished before 1912. A strong contender was the Galerie du Chien d’Or on rue du Fort in Québec City, until we realized that its present aspect dates from after 1965, the year the Barber sketch was included in a Morrice retrospective...; in 1906 it was a tavern, with a totally different look.

Knowing the exact location would be fun, but would perhaps take out some of the mystery of the painting. Morrice’s intention was to introduce his native country to the Parisian public, in the atmospheric style they had started to love, but with a Canadian twist, our winter climate.

To conclude, let us elucidate a small provenance mystery. Donald W. Buchanan, twice (1936 Catalogue Raisonné in his Morrice biography, and 1947 in a smaller book), gives “C.J. Côté” as the owner of Barber Shop, but his 1947 plate is from the 1906 glass negative. In 1936, he also lists Côté for The Doges’ Palace, Venice (priv. Coll.), but before Sir Charles Blair Gordon, who lent it to the 1925 Morrice Memorial Exhibition; the files for that exhibition (MMFA) reveal that he also owned Barber Shop at that point, but did not lend it. So who was this mysterious French Canadian Côté, otherwise unknown as an art collector, who could afford two important Morrice canvases that early?

Charles James Côté was born in Lachine in 1893; his mother was Irish, and he also married one; he worked in English all his life, as a clerk for financial agent G.W. Farrell; in 1914 he became the first Secretary-Treasurer of the new suburb of Hampstead, founded by eight prominent Montreal businessmen, including his employer and... Sir Charles B. Gordon. Although Côté bought some land in Hampstead, he never lived there, and the directory listings suggest that he never became a rich man; it is probably safe to assume that he acted as agent for Sir Charles. By September 1922 Côté left Montreal for good, after his wife Florence had met the painter Frederick William Hutchison in Baie Saint-Paul, at the summer home of Clarence Gagnon; they lived happily ever after, finally marrying in 1939. Côté became an American citizen and never returned to Canada.

Lucie Dorais