Ventes notoires

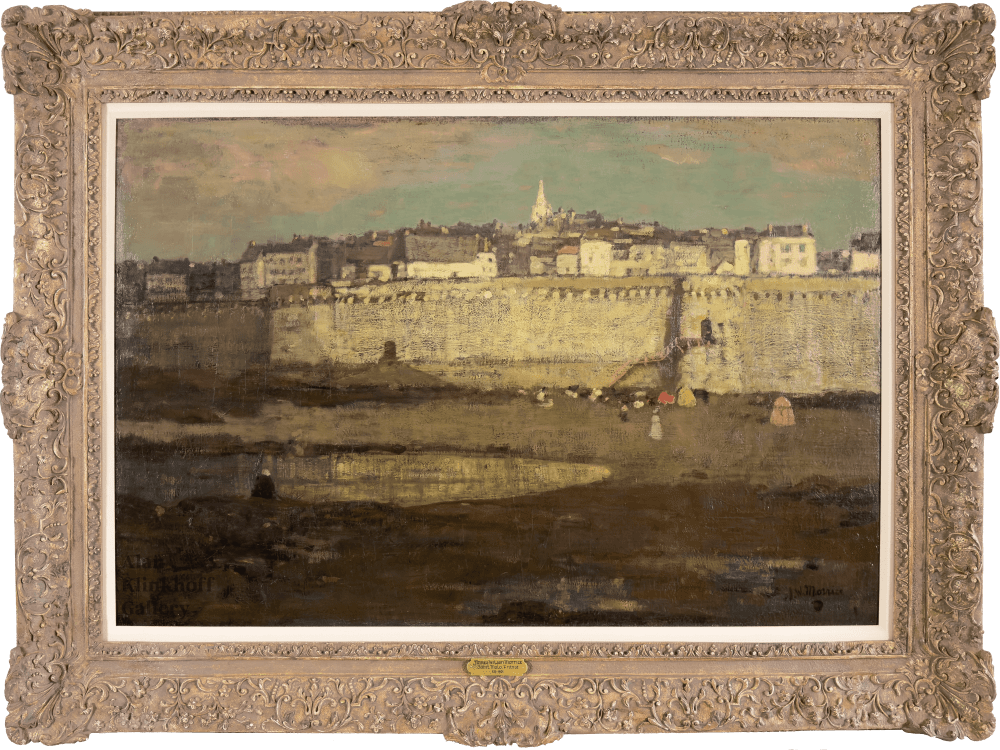

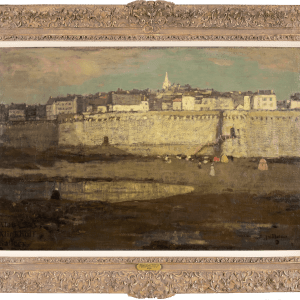

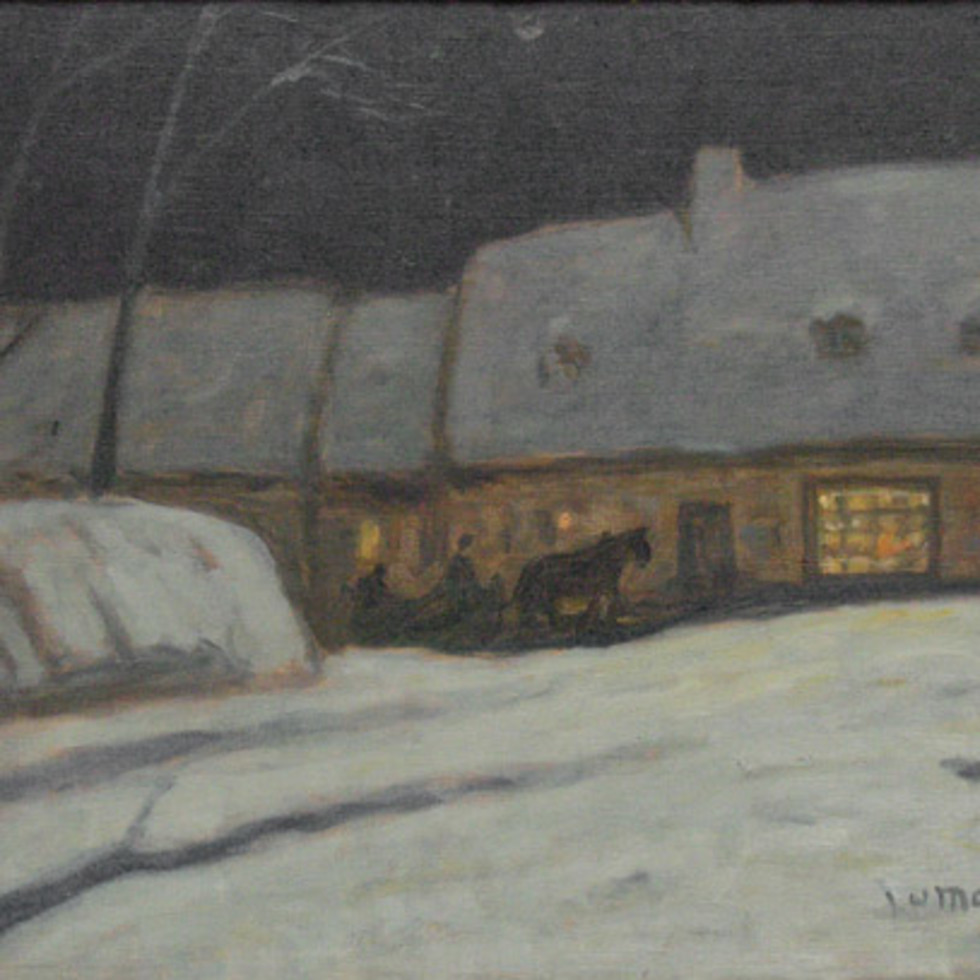

Fig. 1. James Wilson Morrice (1865 – 1924), Vue des remparts

de la ville de Saint-Malo depuis la plage du Bon-secours (View of the Ramparts at St. Malo from Bon-Secours Beach), circa 1901-1902,

Fig. 1. James Wilson Morrice (1865 – 1924), Vue des remparts

de la ville de Saint-Malo depuis la plage du Bon-secours (View of the Ramparts at St. Malo from Bon-Secours Beach), circa 1901-1902, oil on canvas 20 x 29 ins., collection Musée de Picardie, Amiens, France,

inv. no. M.P.3037-1068. (Photo Marc Jeanneteau/Musée de Picardie)

Saint-Malo, France, 1901 (circa)

74.3 x 117.5 cm

Inscriptions

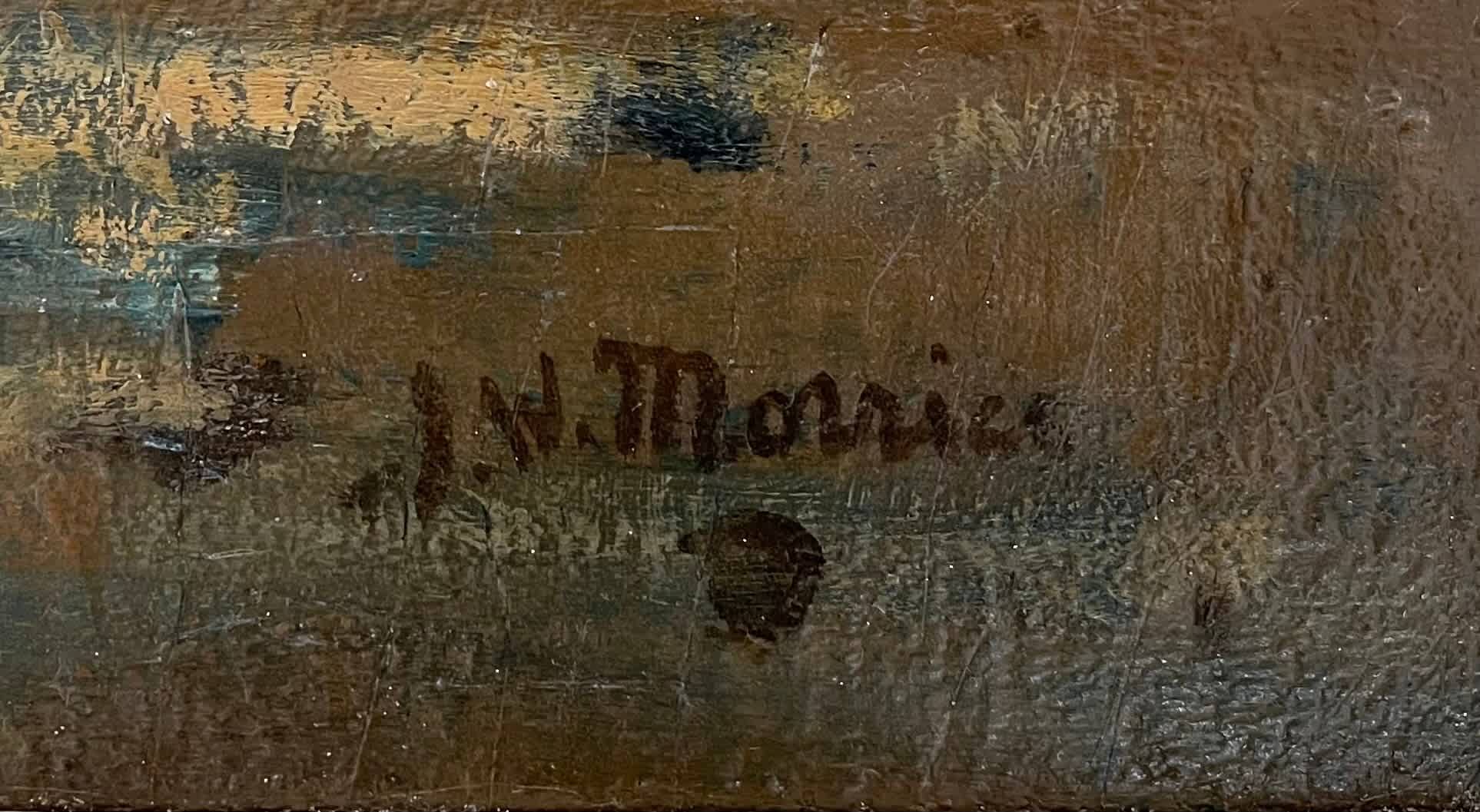

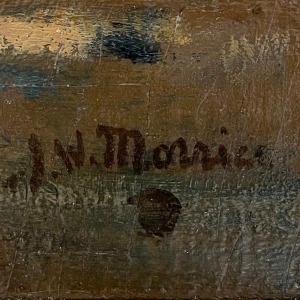

signed, ‘J.W. Morrice’ (lower right)Provenance

George A. Hearn, New York, 1902, purchased at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts 71st Annual Exhibition.

American Art Association, New York, 26 Feb., 1918, Sale of The Notable Art Collection Formed by the Late George A. Hearn of New York City: Merchant, Art Patron and Benefactor, lot 160, as Saint-Malo, France.

W.B. George, New York, 1918, purchased at the above sale;

Lloyd Robbins, New York, by 1936.

Francis Wisner Murray, Jr., New York, before 1971.

Alice Baldwin Murray, Tuxedo Park, New York, 1971, inherited from the above, her late husband;

George Gilbert Williams Keech, 1971, gift from the above, his mother-in-law;

Mary Gertrude Lawrence Murray Keech, 1998, inherited from the above, her late husband;

Private collection, Maryland, by descent.

Expositions

Probably Paris, Grand Palais, XIe Salon de la société des beaux-arts, 22 Apr. - 30 Jun. 1901 (envois pour non-sociétaires), cat. no. 679 as Saint- Malo

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), 71st Annual Exhibition, 20 Jan. to 1 Mar. 1902, cat. no. 189 as St. Malo

New York City, Union League Club (Fifth Ave at E. 39th), Paintings from the Collection of George A. Hearn, 11-13 Dec. 1902, cat. no. 31 as St. Malo, FranceDocumentation

Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 Mar. 1902, p 14, anon.: “Santa Barbara”(title refers to first part of article, a painting); Other notes: the Academy exhibition will close to-day. 15 pictures sold. “The last of this list was a large canvas by the Canadian painter, Morrice, which has been bought by Mr. George Hearn, of New York.”

New York Evening Post, 8 Mar. 1902, p 22, anon: “Art News”, regarding pictures sold at PAFA: “St. Malo,” James Wilson Morrice

(last item in the list)

Vogue v19 n13, 27 Mar. 1902, p ii, “Art”, anon (in the Art supplement section) [unable to retrieve it from https://archive.vogue.com/]

Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 Jul. 1902 p 6, “Academy Picture Sales - Official List”, anon (in the Inquirer’s Summer Magazine)

“... James W. Morrice, ‘St. Malo’...”

Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 Sep. 1902, p 13, “The Art of the Week” (chronicle), anon.

(re publication of PAFA’s permanent collection catalogue); “This year’s list of purchases is... James W. Morrice, ‘St. Malo”...” (in a list)

New York Sun, 13 Dec. 1902, p 8: “Union League Club Exhibition” (anon; prob. Charles FITZGERALD) Mentions landscapes by Daubigny, Hobbema, Inness; a Boudin marine between two Homers, another "seacoast" by James Maris. "Nor should one overlook a very clever and individual rendering of "St. Malo, France, by J.W. Morrice.".

New York Evening Sun, 13 Dec. 1902, p 8: “Exhibitions at the Union League and Lotos Clubs” by Charles FITZGERALD: "Attention must be drawn, however, to a study of the beach outside the walls of St. Malo by Mr. J.W. Morrice, a highly gifted Canadian, little known here, who in the last few years has cultivated an individual and very real talent with unmistakable success."

Privately printed, 1908, catalogue of The Collection of Foreign and American Paintings owned by Mr. George A. Hearn, New York City, Cat. no. 271, as St. Malo, France, ill., page 205, reproduced deluxe picture book, selection of 292 works from the collection, all illustrated in black & white

New York Times, 3 Dec. 1913 p 10: “MUSEUM TO GET HEARN COLLECTION - Dead Merchant’s Art Treasures Are Left to Widow for Life, Probably. - HIS ESTATE $15,000,000 - List of His Private Gallery of Paintings Shows Many Valuable Works.” Article followed by the complete list of his collection, with artists listed in alphabetical order; includes “Morrice, J.W. - St. Malo, France.”

Boston Transcript, 3 Dec. 1913 p 6: “Hearn Art for Public - Another Splendid Gift to New York Museum”, anon bequest expected to go to the Metropolitan Museum, to which he has already given many paintings; his collection includes “St. Malo”

American Art News, v 16 n19, 6 Dec. 1913 p 2: “The Hearn Collections”, anon. A list from his catalog, including Morrice, J.W. - “St. Malo, France”

New York Tribune, 20 Feb. 1918 p 11: “The Hearn Collection of Old and Modern Art” by Royal CORTISSOZ. Describes the preview. "in the modern wing": "Mr. Hearn was not drawn by all the modern movements"; i.e. Impressionists, Whistlerians, and mostly "innovators of recent years". But "interested in the younger men everywhere, when they were to be taken seriously, and his collection admirably shows this... ['Evening in the Desert', J.M. Swan] .. Orpen, Morrice, Lavery, Hornel, are all well represented..."

American Art Association, 1918 De Luxe Illustrated Catalogue of The Notable Art Collection Formed by the Late George A. Hearn: Merchant, Art Patron and Benefactor, New York City, ill unpaginated (lot 160).

New York Sun, 27 Feb. 1918 p 7: “Record Prices for American Pictures”, anon “147 James Wilson Morrice. ‘St. Malo, France.’ W. George 400"

New York Times, 27 Feb. 1918 p 11: “Records Broken at Hearn Art Sale”, anon “160 - St. Malo, France - J.W. Morrice; W. George 400”

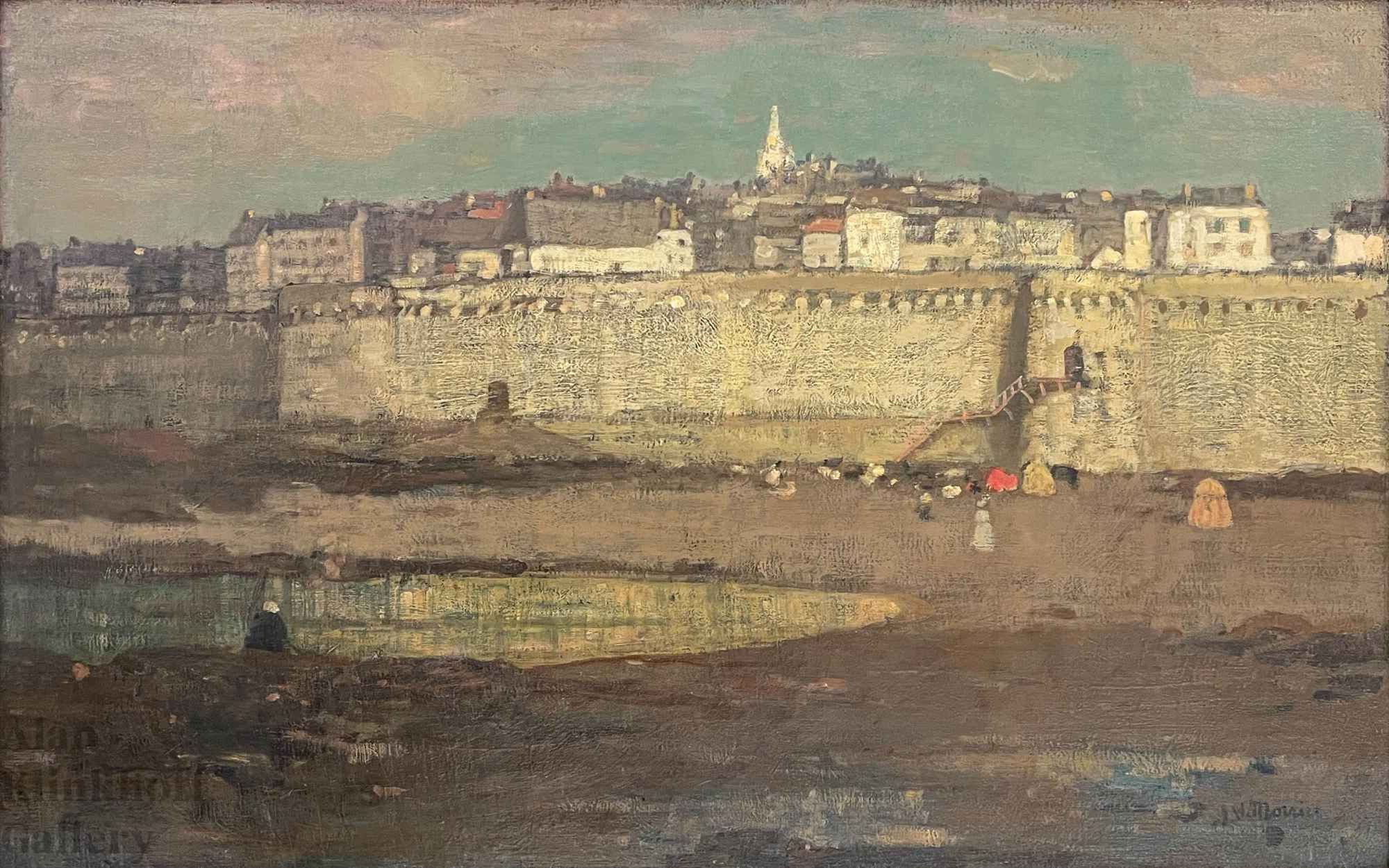

- While Morrice is best known for his small pochades on wood panels, St. Malo, France is well over a meter wide! Definitely rare, but not the artist’s largest canvas (excluding his war mural in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa); that distinction belongs to La Communiante, same width but eight cms taller, which now belongs to the Musée national des Beaux-Arts du Québec. When it was auctioned off in Toronto in May 1978, the surprise was total, and not only because of its size! The Canadian art world, art historians included, had never heard of it. It was not listed in the 1936 Catalogue Raisonné by Donald W. Buchanan (appended to his 1936 biography of Morrice), and the sale catalogue did not mention any provenance. Fortunately, it listed an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1900 (ill. in the catalogue).

The after-sale press release is all about the price (a Canadian record!), and the size of the painting; nothing about the lack of provenance, which was still not well understood in the 1985 Morrice retrospective catalogue (no. 29). Actually, it was purchased right at the PAFA exhibition by none other than the famous American impressionist William Merritt Chase. In 1912, when he auctioned off part of his collection, La Communiante disappeared into American private collections, never exhibited or reproduced until its arrival on Canadian soil in early 1978.

Today, history repeats itself: the largely unknown St. Malo, France entered Canada for the first time last November. It too was purchased at a PAFA Annual Exhibition, that of 1902, by George A. Hearn, a New York merchant prince whose art collection was widely known. In 1906 he gave over 50 paintings to the Metropolitan Museum, and in 1908 self-published a two-volume, fully illustrated catalogue of his collection, featuring Gainsborough’s Blue Boy (actually a good copy)... and close to 300 other paintings. When he died in December 1913, newspapers logically speculated that the remaining paintings would also end up at the MET; they even gave the complete list, including the Morrice. But Hearn bequeathed all to his wife, and they were auctioned off in February 1918, after her passing. St. Malo, France went to a New York dealer and it, too, disappeared into private American collections, known only by its bad 1908 and 1918 catalogue illustrations. D.W. Buchanan might not even know these reproductions, as his 1936 Catalogue Raisonné entry is quoted verbatim from the Metropolitan Museum Library copy of the plain (not illustrated) edition, including the hand-written buyer name and the price he paid; he names a certain Lloyd Robbins of New York as the next owner, but we have not found any information on him yet.

The parallel story of two of Morrice’s largest canvases perhaps does not end there: both are obviously “Salon-size”, and La Communiante was indeed exhibited in Paris, where the artist lived; it was no. 1079 in the catalogue of the Salon de la Société Nationale, in the Spring of 1899. Did St. Malo, France also debut there? No. 679 in the catalogue of the 1901 Salon de la Nationale is simply called Saint-Malo; with no additional information, and no reproduction, it was almost impossible to identify... until we saw the colours of the present painting. Can we see in them the “green sky and pearl grey walls” that Maurice Demaison saw in Morrice’s entry in 1901 (Revue de l’art ancien et moderne)? The other reviews, too vague, don’t help: there are “massive” walls in other Morrice paintings of Saint-Malo, although we must exclude the well-known Beneath the Ramparts, St. Malo (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), a view of the same stretch of wall from the side, which had remained in North America after the (January) 1901 PAFA exhibition. For the time being, St. Malo, France is the best candidate for the 1901 Saint-Malo shown in Paris; or its smaller variant... (see below).

At the turn of the 20th century, Morrice usually spent the end of each summer in the Brittany town, which attracted tourists and artists alike; the old, picturesque city was enclosed by a medieval wall, and surrounded by sandy beaches that made it a popular bathing resort. At first, the Canadian artist was more interested in the bathers than in the architecture; if he included the ramparts, they were only a backdrop. Here there are bathers too, but far away at the foot of the wall, because the tide has just gone out; they are lovely excuses for drops of colour, including Morrice’s near-signature, a red parasol.

The true subject of the painting is not the beach, but the proud city itself, magnified by the sun setting behind us. We stand on the Plage du Bon-Secours, near the path leading to the tiny Grand-Bé island, accessible only at low tide to the tourists visiting the tomb of French writer Chateaubriand. This is the scene depicted in a contemporary postcard, and still visible in Google Street View – with one major change: all the buildings behind the walls have been totally rebuilt after the 1944 bombing, in a more uniform style. Comparison with the ca 1905-1910 postcard reveals the many liberties taken by the artist, who diminished the already small Porte des Champs-Vauverts on the left, and moved it downwards, simplifying its immediate surroundings. The Tour Notre-Dame on the right, with the Porte des Bés and its wooden staircase, conforms better to reality, if only slightly bigger. The portion of the rampart between the two gates has been shortened, and Tour Bidouane, so far left that it does not appear in the photo, has been brought much closer to the Champs-Vauverts.

Rescaling the ramparts is not the only artistic change: the city intra-muros rises on a low hill, dominated by a central, very white steeple. In reality, the sea-level town is on flat ground; the cathedral steeple is taller, grey, and more to the left (it too was rebuilt after the war, in a much simpler style). Whitewashing was also applied on a few buildings over the wall, something also found in Beneath the Ramparts mentioned above (as is, also, the right-shifting of the Tour Bidouane). It certainly adds joy and animation to an otherwise grey vista; the lonely figure from the back, at the edge of the pool, plays a similar role; and, together with the Tour Bidouane above it, it stops our eye from wandering outside the beach... and the painting.

This composition was, obviously, very well planned. Perhaps because it was based on a very small pochade (Queenston, Riverbrink Art Museum), the 1899 Communiante shows signs of heavy reworking in the foliage, something not found here. If there is a preparatory sketch, we have not found it yet; and if Morrice had a sketchbook with him, it has not been preserved. What we have, however, is a mid-size version, at roughly half-size (51 x 73 cm), in the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, France. We have not yet examined this painting, but because it is smaller, and our version does not have any pentimento (a visible change by the artist), we think that the French canvas was painted first. All the elements are already in place, in almost the same position, including the red parasol at the foot of the wall. The small difference in proportions forced the artist to stretch all the left half in the larger version; more significantly, the pool of water is now further away from us, leaving more space for the sandy foreground; it is now darkened by the shadow of the Grand Bé, forcing us to admire the proud city one last time, just before the sun sets below the horizon.

La Communiante and St. Malo, France were sent to Philadelphia because they had not been sold in Paris; Morrice probably followed the advice of his American friends Robert Henri and William Glackens, former students of the PAFA. Excellent advice, since both paintings were sold during the exhibition, among the artists first important sales. Did he have Philadelphia in mind when he painted a third “over-the-meter” canvas? In a way, La Plage de Saint-Malo (81,3 x 114,3 cm,) is the antithesis of St. Malo, France: a large group of bathers, their bath cabins and the horse that brought them there occupies the middle ground; we stand at the edge of the pool of water, looking out towards the open sea. Like it, though, it has an almost identical variant, two-thirds its size (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), as if Morrice was not yet comfortable with that big format, which he never used again. The Plage was purchased by theatre director Jacques Rouché, future director of the Opéra de Paris, before 1909, and remained in his family until just before 1990, when it was acquired for the Thomson Collection (AGO). La Plage and La Communiante are now in public collections, so this is a rare chance to acquire the largest living room format ever tackled by Morrice, and an important milestone in his early career and reception.

-We thank Lucie Dorais, author of the J.W. Morrice Catalogue Raisonne, for contributing the above description. All text and the images featured here are protected by Copyright.