-

Œuvres d'art

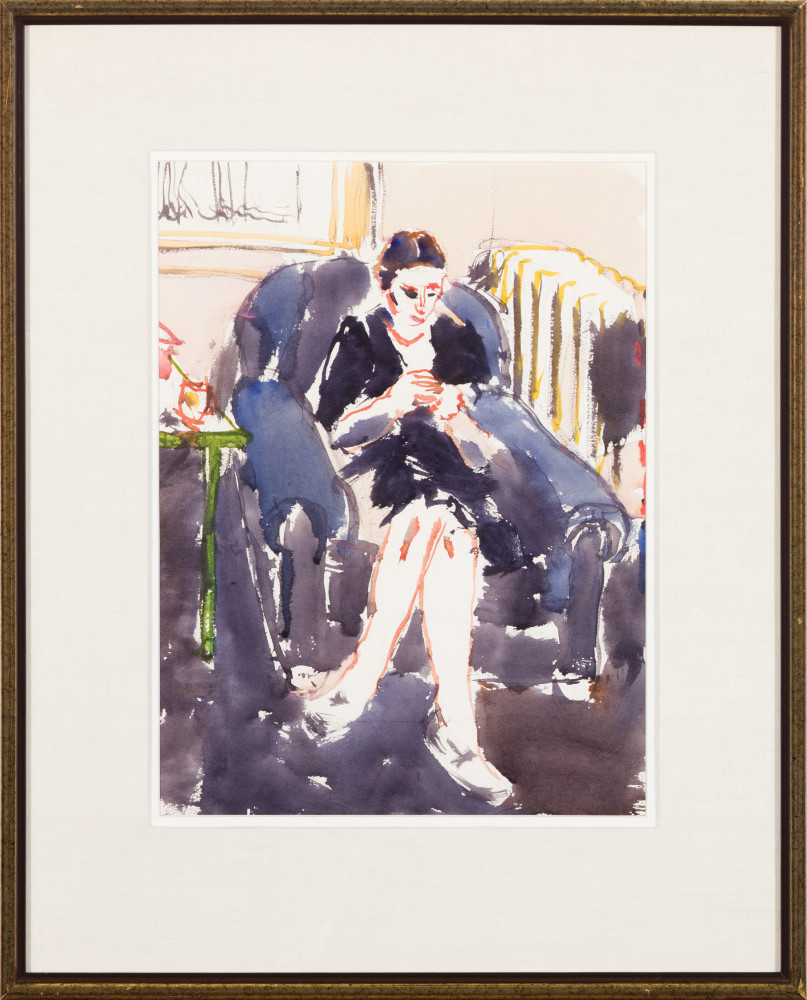

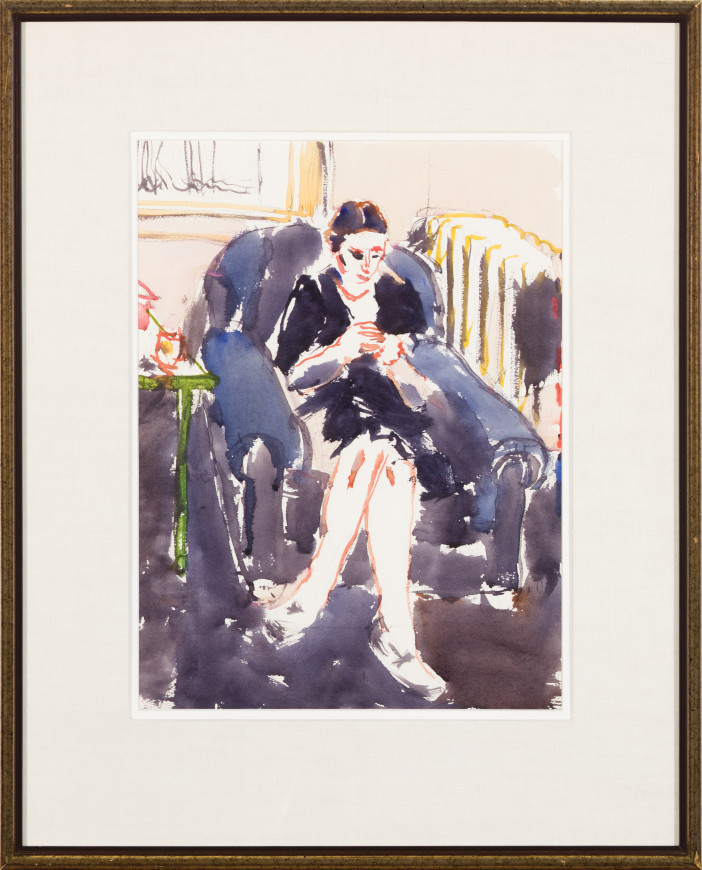

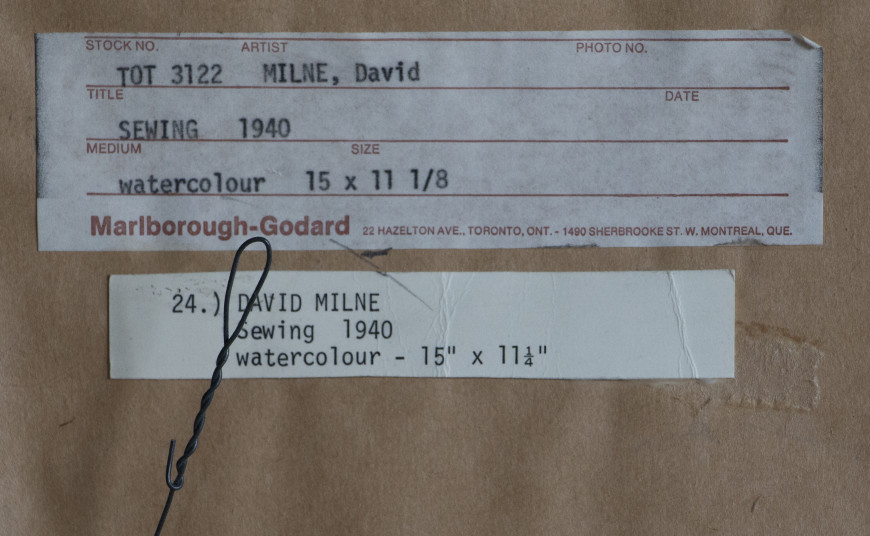

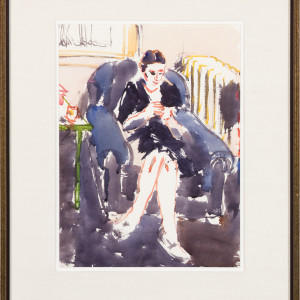

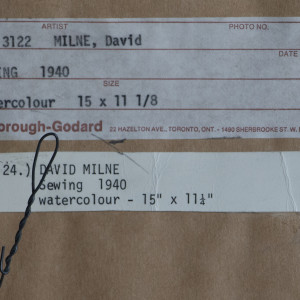

David MilneSewing I, Toronto, 19401881-1953Watercolour on paper15 x 11 1/8 in

38.1 x 28.3 cm

This work is included in the David B. Milne Catalogue Raisonne of the Paintings compiled by David Milne Jr. and David P. Silcox, vol. 2, no.401.40.SoldInscriptions

inscribed, ‘Sewing’ (verso); inscribed by Duncan, ‘W-168 / 176’ (verso); inscribed by the Duncan estate: ‘538 // 178’ (verso)Provenance

Marlborough Godard Gallery, Toronto.

The Collection of Mitzi and Mel Dobrin.

Expositions

Toronto, Marlborough Godard, David Milne: The Toronto Year 1939-1940, 1976, cat. no. 18.

Documentation

Marlborough Godard, Toronto, David Milne: The Toronto Year 1939-1940. Introduction by David Milne Jr. Exhibition catalogue, Toronto: Marlborough Godard Gallery 1976, cat. no. 18, p.11, repr. p. 22.While it’s natural to think of Milne as a landscape painter, the domestic was a strong, and not unrelated, interest in his work, especially in his later career. He was a builder of cottages and homes and revelled in the temporary ‘camps,’ the ‘painting places’ that he set up on picture-making excursions.He frequently depicted the interiors of his shelters, whether permanent or temporary. In these interiors, Milne showed the materials and tools of artmaking to such an extent that many such works are in fact meta-paintings, reflections on the artform itself. Not one to depict himself very often, instead, materials objects and especially his female partners resonate with an intimacy that potently, if invisibly, imply the presence of the artist.

In these two unpretentious, but affecting, portraits, we see Kathleen Pavey, with whom Milne began a relationship in 1938. He met her at Six Mile Lake, where she was on a camping trip; Milne seems to have rescued Kathleen from a near mishap in her canoe during a squall. She was then twenty-eight while Milne was in his fifties. Milne moved from Six Mile Lake to Toronto in the summer of 1939 to live with Pavey. Typically for Milne, they shifted from address to address. He was again stimulated by urban surroundings, painting numerous watercolours in various parts of the city and making contact with a range of artists and collectors. A child on the way, however, the couple moved to northeast of Toronto to the small town of Uxbridge, Ontario in 1940. During the year in Toronto, Kathleen was pictured in Milne’s work approximately forty times. In these two portraits, she is visualized in their domestic setting, absorbed in her hand work. While Milne has sketched Kathleen quickly in watercolour – as noted above, calligraphic speed is palpable in this work, suggesting directness – the sophistication of his technique and intensity of his observations should not be underestimated.

More than any other painting medium, watercolour is suited to staining large areas of the surface with liquid colour; this we see in the vibrant purples and soft browns that he uses for the floor in both works and also in smaller areas such as the pinks of Kathleen’s face and blouse in The Knitter. In contrast to Stream in the Bush (Boulders in the Bush II) and Channels in this collection of Milnes, this is palpably ‘wet’ painting. Yet Milne’s painterly prowess shines in how he controls this fluid medium with the firm, largely rectilinear architecture of a chair, a table, what appears to be a laundry drying rack in The Knitter, and the vertical lines of radiators in both pictures. Large portions of each picture are left open and white, adding the sense that we are glimpsing a scene that is in flux.

Kathleen Pavey was a nurse, not an artist, but Milne’s choice to show her dexterity and concentration in these images might suggest that these works are in part about characteristics crucial to Milne the painter, that they reflect on Milne and on painting itself as well as Kathleen Pavey. She does not acknowledge that she is being painted – she is not posing – yet the depiction of a manual craft suggests a bond. She is perhaps knitting for their unborn child, as she mentions in her diary. We sense that Milne is there too, even though she doesn’t acknowledge his presence. As usual, these paintings are challenging to Milne technically and to his viewers. For example, how does he include so much visual pattern and yet capture the likeness of the all-important sitter? In Sewing, Kathleen’s form stands out against the washes of colour on the chair and floor because – ironically – her limbs are not painted, but only quickly outlined.

While these are not large paintings in any sense, they participate significantly in an important art historical category with which Milne was familiar from his time in New York City: the approach known as ‘Intimism.’ Best appreciated in the work of late 19th - to early 20th-century French painters Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard, Intimism represented seemingly every day domestic interiors, very often focused on a lone female sitter involved in domestic duties or reading. In Vuillard’s paintings especially, decorative motifs such as floral wallpaper would often seem to overwhelm if not quite dissolve these human protagonists. Milne had painted several such scenes of Patsy in New York, c. 1913-14. Both watercolours and oils, these include Striped Dress, Red, and The Yellow Rocker. These two paintings of Kathleen Pavey from 1940s are much simpler and more immediate than the New York paintings, yet they also share many of the concerns, qualities, and pleasures of Milne’s early essays in Intimism.

Mark A. Cheetham1sur 4