-

Œuvres d'art

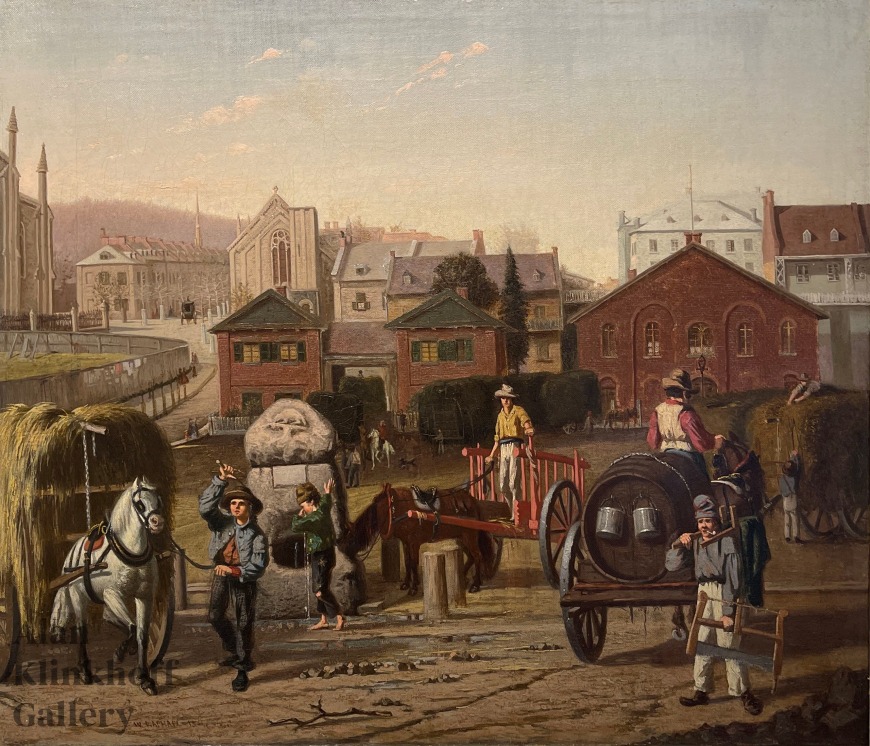

William RaphaelSquare Victoria, Montreal, 18611833-1914Oil on canvas20 1/8 x 25 in

51.1 x 63.5 cmSoldInscriptions

signed and dated, 'W RAPHAEL 1861'Provenance

An Important Corporate Collection, Canada

Heffel Fine Art Auction House, Fine Canadian Art, August 25 2022, lot no. 642

Initially called Haymarket Square, renamed Victoria Square for the 1860 visit of the Prince of Wales (a year before the canvas).

See: https://www.klinkhoff.ca/blog/8385-william-raphael-masterpiece-resurrected-from-anonymity-by-alan-square-victoria-montreal-previously-describes-as-untitled-townscape/

Although just recently sold by Alan Klinkhoff Gallery, it is a pleasure to share this important and rare discovery made by our team with interested stakeholders, both buyers and sellers of important fine art. The story of the burgeoning City of Montreal in the pre-Confederation days “told” by the skillful brush of the master William Raphael, is of enormous benefit to the canon of 19th Century Canadian art. This particular painting along with Behind Bonsecour Market, 1866 at the National Gallery of Canada, demonstrates a quality of painting by William Raphael at a par with the finest and best known artists of the period.

The backstory of our discovery deserves to be told. Beyond the “value added” to the painting and to its new owner by the research Galerie Alan Klinkhoff undertook, the rest of the takeaway we are best to leave to our audience. The painting was offered for sale at auction in the summer months and accompanied with a description limited to Untitled (Townscape) and the name of the artist, his dates, the medium and the size of the work. That we were able to purchase Untitled (Townscape) alias Square Victoria, Montreal for all intents and purposes uncontested might be in part attributed by some to the absence of a reasonable identification of the scene. To others, this might suggest a certain numbness by traditionally interested parties caused by the extraordinary quantity of “art” offered at auction monthly online. This enormity of supply serves to increase the financial risk incurred by the consignor.

The best of William Raphael is well positioned in the art market. It was only 5 years ago when we underbid the very fine Bonsecour Market, small (12” x 16”) by William Raphael offered by Peter Winkworth’s estate in London. That painting achieved a handsome and merited value.

William Raphael (1833- 1914) was one of the foremost artists of the last half of the 19th century active in Canada. Raphael was born in 1833 in Prussia to parents who were Orthodox Jews of Polish descent. According to research by Sharon Goelman for Galerie Walter Klinkhoff in 1996 William Raphael arrived in Montreal via New York City on April 23, 1857. The painting described here is of an importance in his oeuvre only matched by the National Gallery of Canada’s Behind Bonsecour Market, 1866. Raphael was the first artist of the Jewish faith to establish himself in Canada. [1]

Haymarket Square was initially used to designate the Place des Commissaires, a formal market established by city commissioners James McGill, John Richardson, and Jean-Marie Mondelet in 1810. The change to Victoria Square occurred in 1860, the year before this Raphael was painted. The market was situated just outside of Montreal’s fortification walls, which the commissioners had commenced the destruction of in 1801. They decided on this location because it acted as a middle point connecting the city to the farms where hay was harvested. A haymarket was crucial for Montreal where horses and cattle drawn vehicles were the only available modes of transportation and delivery. Moreover, this space was in proximity to the city’s stables (such as the U shaped Youville stables) and warehouses (“entrepots” for grain, wood, etc). During the late 1820’s, a wood market was set up next to Place des Commissaires, accordingly crystallizing this area’s function as a commercial space catering to Montreal’s urban population. [2]

In 1841, the city purchased a field between Craig and Jurés streets facing Place des Commissaires to expand the Haymarket. This section of the square became informally known as Beaver Square. The city also invested in new equipment and infrastructure for the market’s relocation across the street. Meanwhile, Place des Commissaires was paved and transformed into a public space (park). [3]

The Square’s name was changed to Victoria Square in October 1860, following the visit of Queen Victoria’s son (the then-Prince of Wales [later King Edward VII]) to Montreal. This decision was greatly debated during municipal council sessions. Many aldermen argued that the change would erase Beaver Square’s history as a haymarket. Meanwhile, they deemed that changing the Place des Commissaires name would be disrespectful towards the commissioners. [4] At this time, the square comprised the market (Beaver Square) and Place des Commissaires.

Beaver Square retained its purpose as a haymarket until 1865, when the market was moved to a larger space (near Chaboillez Square). This relocation was prompted by the city’s inauguration of a horse-drawn tramway system in 1861, which amplified the demand for hay. [5]

We are grateful to Dr. Laurier Lacroix, C.M. for his assistance in identifying the buildings in William Raphael’s Square Victoria composition. We acknowledge Marie-Lou Boyle and Yasmeen Khoury of Galerie Alan Klinkhoff whose important research complemented that of Dr. Lacroix.

Below are the main buildings that we were able to identify in Raphael's painting showing the Haymarket:

1. St Andrew Church

The church on the left, of which we see a part with the pinnacles: St. Andrew Church (presbyterian) was built in 1851. It burned down in 1869.

2. Messiah Church

In the center, without a bell tower, is the Messiah Church (Unitarian) which was inaugurated in 1857. It was built by architects Hopkins, Lawford & Nelson.

3. Beaver Hall Terrace

Between St Andrew Church and the Messiah Church is a series of terraced houses built on the Beaver Hall Hill referred to as The Beaver Hall Terrace. [6]

The Beaver Hall Terrace was designated as the “New Town of Montreal” a reference to Edinburgh’s famous New Town plan of 1767. Similar to the Prince of Wales Terrace, which used to be located at the Sherbrooke and McTavish St. intersection, where Mcgill University’s Desautels building and McLennan library are now situated.

4. St. Bridget's Home

On the top line, the gray stone building with a 4-sided gray roof and lucarnes (dormers) was the first location of St. Bridget's Home.

This mansion was built by Pierre de Rastel de Rocheblave in 1819. The Sulpicians purchased Rocheblave’s land and mansion from his widow in 1843. They commenced the construction of Saint-Patrick Church the same year and finalized it in 1847. Meanwhile, the neighboring mansion became St. Bridget’s Home and Refuge’s first location. In 1869, St. Bridget’s was moved to a new building a short distance away. The Rocheblave house was beyond repair, and was demolished around 1900. By this time, the area was mainly commercial.”[7]

St. Bridget’s Home was established by religious authorities in response to the influx of Irish immigrants to Montreal seeking to escape the 1847 Great Famine.The Refuge cared for the ill, unemployed and homeless. [8]

5. Vacant lot

On the left is a large fenced vacant lot that is unoccupied. There are signs (posters) posted.

6. Scales for weighing hay

On the market place is a red brick building in the center in two symmetrical parts (green window shutters): where the scales for weighing hay loads were located.

In 1841, the amount of 5982 pounds, 15 shillings and 8 pence was spent to purchase land for the enlargement of the Haymarket and the erection of a new hay scale building, or weigh house, the purchase of a scale and the construction of a clerk’s house. The project was completed in 1844. The weigh house was built of brick. For the scale at the new Haymarket, the City Inspector stated that a machine with a three-tone load would be required. On November 4, 1843, engineer George Murray claimed that a machine with a capacity of three to four tons would cost about 44 pounds. Montreal Archives. However, according to The Herald (November 19, 1897), the weigh house was built in 1842. [9]

7. Drinking fountain

The fountain was a drinking fountain for people and included a trough for horses. In the foreground is a beautiful detail of the fountain of the Haymarket, “la fontaine de sante”, surmounted by a stone on which is carved a beaver. Raphael has captured a child drinking. The fountain was destroyed by a car collision in 1946.[10]

Raphael has grouped some of Montreal's small trades in the foreground: the hay carters, a water vendor, a wood sawyer. It is noteworthy that the artist chose a perspective toward the Square that omitted St Patrick's Church which was located immediately to the right of the Rocheblave mansion which became St Bridget's Home and on the same property. One is inclined to suggest that Rapael had an interest in focusing on the market activity itself. See below a watercolour of 1853 by the artist James Duncan depicting the Gavazzi Riot that occurred at the same site.

Figure: James Duncan, Gavazzi Riots, 1853. Collection of the Museum of Civilization

The following photo shows St. Andrew's Church and St. Patrick's Church in 1851. Some of the houses depicted by Raphael can be seen. This of course is from a different angle than the one from which Raphael approached his work.

Provided by Laurier Lacroix

[1] Sharon Goelman, “William Raphael, R.C.A. (1833-1914)” (Masters thesis, Concordia University, 1978), ix.; Sharon Goelman, “William Raphael, A.R.C. (1833-1914),” in William Raphael Retrospective Exhibition, 7-21 September 1996 (Montreal: Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, 1996), 1.

[2] Guy Pinard, Montreal: son histoire, son architecture (Montréal: La Presse, 1987), 184-185.; Karim Wagih Fawzi Youssef, “Le Développement Morphologique du Square Victoria à Montréal” (Masters thesis, Université de Montréal, 2002), 13, 43.

[3] Youssef, “Le Développement Morphologique,” 26.; Ibid., 23, 36.

[4] Pinard, Montreal, 187. ; Youssef, “Le Développement Morphologique,” 41.

[5] Youssef, “Le Développement Morphologique,” 42.

[6] David B. Hanna, “Creation of an Early Victorian Suburb in Montreal,” Urban History Review, 9, no. 2 (1980): 50.

[7] Sandra Stock, “Traces of Charity: St. Bridget’s Refuge,” Quebec Heritage News, 13, no.1 (2019): 10.

[8] Guillaume Saint-Jean, “St. Bridget's Refuge, le refuge oublié,”Le Devoir, 13 July 2009.; Stock, “Traces of Charity,” 10.

[9] Youssef, “Le Développement Morphologique,” 27.

[10] Pinard, Montreal, 192-193.