Fritz Brandtner and Northwest Coast Art

Potlatch, B.C. and Mr. Arthur Gill by Alan Klinkhoff

In our research, we uncovered that Potlatch, B.C. was once owned by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Gill of Montreal, who lent it to the 1971-2 travelling exhibition, Fritz Brandtner: 1896-1969: A Retrospective Exhibition. Walter Klinkhoff, in his Reminiscences of an Art Dealer, recalled his interactions with Arthur Gill. Arthur B. Gill became a good and valuable friend of the Walter Klinkhoff Gallery from Dad’s earliest days selling pictures and remained a family friend. As Dad wrote below, Arthur Gill “accumulated a superb collection” of art work, a collection which included our Brandtner Potlatch, B.C. featured here. Other of Gill’s paintings which are well published include Afternoon, Saint Simeon by Albert Robinson and Fishermen’s Houses by Edwin Holgate, both of which he donated to the McMichael Collection as well as Anne Savage’s Ploughing, which he donated to The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

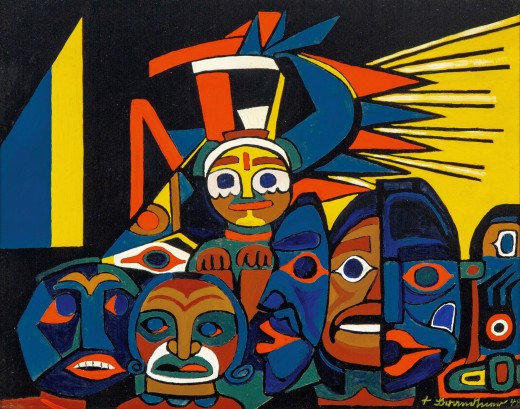

Friedrich Wilhelm (Fritz) Brandtner 1896-1969, Potlatch, B.C., 1948

Oil on masonite, 8 x 10 in (20.3 x 25.4 cm) This work is sold.

Dad wrote that when he opened his first storefront it was located just up the street from Arthur Gill’s office. When Place Ville Marie opened Gill along with the Morgan offices relocated to this new prestigious address. Dad had by then moved his gallery up to Sherbrooke Street, only a 10 minute stroll for Arthur Gill’s visits.

Although I don’t have any memories of Katie & Arthur Gill’s Town of Mount Royal home, I do remember quite vividly their apartment on Kensington in Westmount, an address only 300 or 400 meters from where Helen & I have now lived for more than a decade. Their son, Bruce, we bump into occasionally. Bruce, probably now retired had a distinguished career as an investment adviser with a prominent firm. He became quite a stalwart in his support of The Church of St. Andrew & St. Paul where Dad had at one point been senior elder and, by the way, the same church where I was baptised. The “A & P” is located literally a stone’s throw from our present Montreal gallery.

Dad wrote in his Reminiscences of an Art Dealer that he first met Arthur Gill,

“...following a telephone call I received, inquiring if I had anything by Albert Robinson. I had, Gill bought it and a friendship developed. I was still operating from the upper duplex on Van Horne Avenue at that time, living below on two levels with my family. Arthur started collecting Canadian paintings. Previously he had liked the British 19th century landscapes and had bought some of dubious authenticity at auction. He became a great enthusiast, had a very good eye and boundless energy. Arthur was President of both Morgan Insurance and of the storage firm and sat on the board of the other Morgan companies. He had tremendous business contacts and through the insurance and storage firms he knew the whereabouts of many paintings that were insured and stored. His enthusiasm for Canadian art was infectious and formed the subject of all of his conversations. He sent me many prospective buyers and was a tremendous help in the early years. When I rented my first premises on Union Avenue, his office was just down the street. He seemed to have very much time and so did I. There was very little traffic, few telephone calls, little business. Every morning Arthur and I sat together in the Gallery having a cup of tea and most days we did the same in the afternoon. Arthur knew every painting I had or was going to get. I sold paintings to some of his connections every week. Instead of a commission, I would let Arthur have any painting he wanted for his own collection at cost. It was a good deal for me. Later on, Arthur did sometimes give me paintings to sell, or bought some with me in partnership. He accumulated a superb collection which was sold after his death by his widow, leaving her better off than she otherwise would have been. It had been a good investment.” [1]

Northwest Coast Art and Fritz Brandtner

Nadine Di Monte

In the exhibition catalogue for the show organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, The Brave New World of Fritz Brandtner, scholars Helen Duffy and Frances K. Smith note that,

In 1930, Brandtner made his only visit to the west coast. For him this was, in part, a fulfilment of a childhood interest, through books, in the art of the West Coast Indians [sic]; of the original art, all he had seen in Europe were a few totem poles in museums. It was a revelation to him. [...] Many works emerged from this experience [...] But more important was his absorption of the motifs of the Indians [sic] used in the totem poles into a personal iconography. He had a remarkable capacity to grasp the abstract design aspects of these motifs to transmute them into something quite personal [2].

The Brave New World of Fritz Brandtner makes brief reference to Brandtner’s literary interests. Brandtner’s wife, Mitzi, in her interview with Charles C. Hill, former Curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada, recalled that her husband’s “mother bought a book for him. It was in German, written in German, of course. And he liked that so much he wanted to go to Canada [3].” In his personal library, now at the National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Brandtner retained a copy of the publication Downfall of Temlaham by Marius Barbeau, with illustrations by Edwin Holgate, among others. Barbeau’s book was published in 1928, as Brandtner’s arrival in Canada was in the same year, it can be surmised that this book was amongst the first purchases of the newly immigrated artist [4]. Jonathan Franklin, the former Chief of the Library and Archives (NGC) wrote,

“It is quite possible, however, that the first book he [Brandtner] purchased in Canada was based on ancient Gitksan oral traditions: The Downfall of Temlaham by Marius Barbeau (1928) [...] His copy survives in the jacket he made for it himself, of coarse cloth, decorated on the front with a motif in coloured ink, inspired by Haida house post designs [5].”

In his copy, Brandtner inscribed on the title page, “F. Brandtner / 1928 / Winnipeg / bought after the fire / on Main street / for 10 cent [6].”

Just two years after his purchase of Barbeau’s book, Brandtner — newly employed at Brigdens of Winnipeg Limited — travelled to Canada’s west coast. Mitzi, when recounting her trip to Hill in the same interview cited above said, “We went to Prince Rupert, up in between we were in some places where there were factories. [...] He painted a tremendous amount, not right on the spot, but later on [7].”

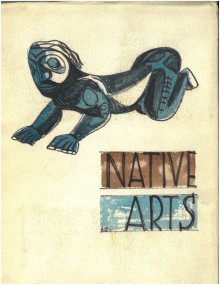

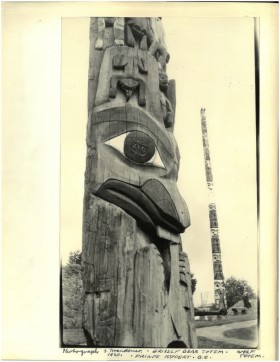

Years later, Brandtner would journey to the east coast of Canada. In addition to his posts as a teacher in Montreal, which we have touched upon before, Brandtner, from 1949-1953, taught summer school at the University of New Brunswick [8]. A copy of the 1949 publication Native arts of the Pacific Northwest: From the Rasmussen Collection of the Portland Art Museum was gifted by ten of his students to Brandtner [9]. Like he had with Downfall of Temlaham, the artist created his own dust cover for the monograph, tipping on to its pages his own personal ephemera, including one picture of the totems at Prince Rupert from his 1930 trip [10].

The hand-drawn cover of Brandtner’s copy of Native arts of the Pacific Northwest: From the Rasmussen Collection of the Portland Art Museum [11]

Brandtner’s photograph from his 1930 Trip to Prince Rupert, “Photograph F. Brandtner - Grizzly Bear Totem. - Wolf Totem. - 1930. - Prince Rupert. B.C.” [12]

Historically, the potlatch was a ceremony at which wealth was distributed. Commonly understood as a gift giving occasion, it is important to note that practice and formality differ among First Nations. An amendment to the Indian Act banned potlatches, citing them as wasteful and destructive [13]. The prohibition was modified over the course of this 67 year period to include prison sentences for violations, including the possession of masks [14]. Though the practice was continued in secret, the ban was not lifted until 1951 [15].

Brandtner’s work approaches the potlatch without any specific details of a particular Northwest Coast society in mind. Brandtner, it seems, was intrigued by the way the Northwest Coast art defied ‘conventional’ artistic languages and the incredibly Modern aesthetic that the art offered [16]. Brandtner’s figures pay homage to the motifs and shapes found in the art produced by the First Nations of Canada’s Pacific Northwest, which in Potlatch, B.C., are articulated through Brandtner’s own artistic language. Here Brandtner freely integrates the ovid and line forms of the Northwest Coast ornamentations but with considerable distortions. The abruptly dislocated features of the figures overlap and jostle one another on Brandtner’s pictorial plane, like figures in motion. The colours recall the traditional black, red, blue, and green of Northwest Coast art, as well as the yellow found in the art and objects of the Kwakwaka'wakw; the tan elements suggest the exposed wood carvings of the indigenous artistic cultures. Notably, however, Brandtner has altered the shades of his blues to give a sense of three-dimensionality.

In the late 1940s, Brandtner made at least one other oil painting from a sketch conceived during his 1930 trip [17]. What stirred up the memories of this sojourn, we can only speculate. In June 1947, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild sponsored an exhibition of art and objects by First Nations. The show was held at the Montreal Art Association where the works were arranged geographically. Objects from the Northwest Coast included a Chilkat blanket, a Haida chest, and the mask collection of the British Columbia Indian Arts and Welfare Society [18]. Alice Lighthall, then chairperson of the Indian and Eskimo Committee of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild of Quebec, explained that “many of the exhibits were the result of entries in a nationwide contest for modern Indian [sic] craftsmen sponsored by the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, to overcome the reluctance of many young Indians [sic] to learn the traditional techniques of their people [19].” With its stated efforts to help inspire young, contemporary artists, it is entirely conceivable that this exhibition appealed to Brandtner as both an artist and an educator.

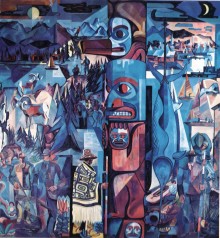

In 1945 the massive 12 by 13 foot mural for the new ticket office of the Canadian National Railway in Boston, executed by Brandtner over nine separate panels, was unveiled [20]. The mural was meant to describe Canada as a “tourist playground” and features Brandtner’s representation of a Northwest Coast totem pole prominently in the centre of his image [21]. To the left of the totemic object is a man in a stylized Chilkat blanket and a cedar hat, each decorated with Brandtner’s modified designs that were inspired by Northwest Coast motifs. As Brandtner conjured the images for his CN mural, his interest in the art and objects of the Northwest Coast was undoubtedly reinvigorated.

Brandtner’s mural for the ticket office of the Canadian National Railway in Boston [22]

Regardless of the source — or sources — of his renewed inspiration, what cannot be denied is the influence that the distinctive, remarkable formline design of the Northwest Coast art had on Brandtner’s aesthetic.

Alan Klinkhoff Gallery would like to extend thanks to Mr. John Boylan, Public Services Archivist, Public Archives and Records Office of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PEI and Ms. Annie Arseneault, Interlibrary Loans, Library and Archives, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON for their assistance in our research.

Endnotes

1. Walter H. Klinkhoff, Reminiscences of an Art Dealer, (Montreal: Walter Klinkhoff Gallery, 1993), p. 44-5

2. Helen Duffy & Frances K. Smith, The Brave New World of Fritz Brandtner, (Kingston, Ont.: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, 1982), p. 26. N.B. I have reproduced the 1982 text as published. The word “Indian” is used incorrectly in Smith’s / Duffy’s identifying of the Northwest Coast peoples.

3. Charles C. Hill interview with Mitiz Brandtner, Mitzi Brandtner in conversation with Charles Hill, 12 September 1973, Canadian Painting in the Thirties Exhibition Records, National Gallery of Canada Fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, transcribed 31 March 2008, p. 6

4. Jonathan Franklin, “An Artist’s Library: Books from the Collection of Fritz Brandtner”, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, 13 January 2014, https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/exhibitions/an-artists-library-books-from-the-collection-of-fritz-brandtner

5. Ibid.

6. Jonathan Franklin, “Portrait of the Artist as Reader: The Fritz Brandtner Library in the National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives," National Gallery of Canada Review, Vol. 7, 2016, p. 98

7. Hill / Brandtner, Interview, 1973, p. 43

8. Duffy / Smith, 1982, p. 40

9. Franklin, 2016, p. 99

10. Ibid.

11. The hand-drawn cover of Brandtner’s copy of Native arts of the Pacific Northwest: From the Rasmussen Collection of the Portland Art Museum, Courtesy of Ms. Annie Arseneault, Interlibrary Loans, Library and Archives, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON

12. “Photograph F. Brandtner - Grizzly Bear Totem. - Wolf Totem. - 1930. - Prince Rupert. B.C.”, Courtesy of Ms. Annie Arseneault, Interlibrary Loans, Library and Archives, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON

13. Sara Davidson and Robert Davison, Potlatch as Pedagogy, (Winnipeg, MB: Portage & Main Press, 2018), p. 2

14. Carolyn Butler Palmer, “Negotiating ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art ‘As Family Narrative’”, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2/3, p. 191

15. Davidson / Davidson, 2018, p. 27

16. I note that any ‘representation’ of land, nature, and environment relating to the Northwest Coast can be understood as being inherently politically charged. It is unlikely that in 1948 Brandtner was aware of the cultural and political complexity of the situation but he clearly felt that the art objects produced by the First Nations of the Northwest Coast merited more exposure. I believe that the work should be understood with the knowledge that in 1948 there was much that would have limited Brandtner’s social and political gaze.

17. Duffy and Smith note that the 1950 oil work, Spirit of Ka-Ku (their cat. no. 52) is related to the 1930 watercolour of the same title (their cat. 15), see: Duffy / Smith, 1982, p. 56

18. “Colorful Indian [sic] Crafts on View at Canadian Handicrafts Show," Gazette (Montreal), 7 June 1947

19. Ibid. N.B. I have reproduced the 1947 text as published. The word “Indian” is used incorrectly in identifying of the Canada’s First Nations.

20. “Mural Depicts Vacation Attractions of Canada”, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, NY), 22 July 1945, p.11

21. ArtsCanada, Vol. 1, 1943, p. 135

22. Reproduced in colour in Duffy / Smith, 1982, fig. 14, unpaginated