Arthur Lismer in Bon Echo

Dominating the eastern shoreline of the Mazinaw Lake is an enormous 1.5 kilometre granite cliff that rises 100 metres from the lake's surface. Skirting the visible base of the Mazinaw Rock is a collection of some 200 red-ochre pictographs, believed to be painted by Algonquin ancestors. The name Mazinaw is derived from the Algonquin word Mazinaabikinigan-zaaga'igan, meaning "painted-image lake" [1]. Scholar Robert Stacey writes, "the aboriginal name is doubly appropriate, because Mazinaw Lake, and especially the 'Rock' [also referred to as the Bon Echo Rock, Mazinaw Rock, or the Big Rock,] has been one of the most frequently painted landscapes in all of Canada since the turn of the century" [2].

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

One of 295 pictographs located along the base of the Mazinaw Rock. The pictographs were composed using red ochre (hematite). The above pictogram is believed to depict the Rabbit Man (Nanabush or Nanabozko), an important figure in Anishinaabe mythology.

Stacey sought to chronicle and illustrate the art history of Mazinaw Lake and its great Rock, in his publication Massanoga, The Art of Bon Echo. The book was intended by Stacey to be the first volume in a series called Art and Artists in the Parks [3]. In his article on Robert Stacey in the National Post, Robert Fulford writes, "Dennis Reid, chief curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario, praised Stacey's sense of art's context -- he was 'a cultural geographer.' Stacey loved to write about places where artists found inspiration [...] He believed we should ignore broad schemes for nationhood and focus instead on regions that provided the seedbeds of culture: "'We need to rediscover the power of place'" [4].

Bon Echo [Fig. 1] was painted early in Lismer's career as a member of the Group of Seven, during one of two trips to the area in the early 1920s [5]. During his sojourns, Lismer stayed at the Bon Echo Inn, a hotel situated on the peninsula directly opposite the Big Rock. Beginning in 1913, under the ownership of Flora MacDonald Denison, the Inn became a hub for visitors interested in paintings and other areas of the arts. After her death in May 1921, Flora's son, Merrill Denison and his then-fiancée, Muriel Goggin took over management of the Inn [6]. Merrill was a playwright-in-residence at the Hart House Theatre and member of the Arts and Letters Club, which brought him into contact with many of the members of the Group of Seven [7]. A number of the Group members assisted Merrill in his productions as set designers and consultants [8]. As a consequence of their professional relationships, most of the Group of Seven, including Lismer, would patronize the Bon Echo Inn.

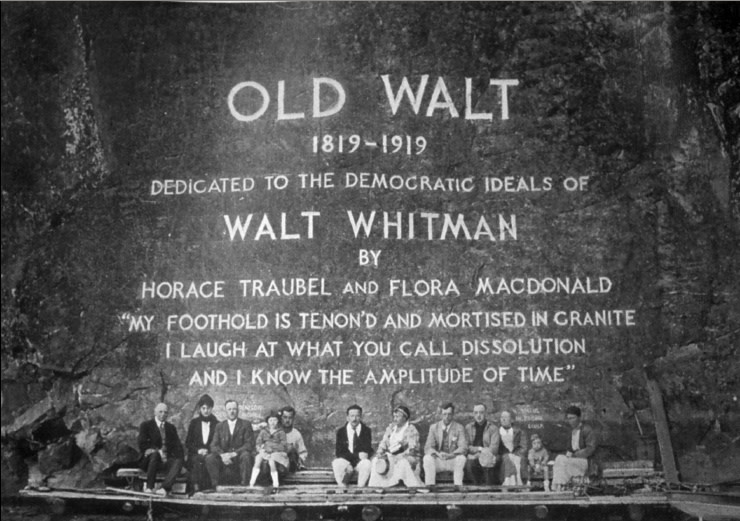

Fig. 3 Inspired by the humanist ideals and poetry and Walt Whitman, Flora MacDonald Denison commissioned two stonemasons to chisel Whitman’s words into the Mazinaw Rock face. Above is the dedication of “Old Walt” in August 1919. Flora MacDonald Denison is under the “P” in “amplitude.” Merrill Denison is under the word “know.”

Lismer, his wife, and daughter visited Bon Echo Inn in 1921 and 1922 [9]. Subsequent to their stay, the Denisons named one of their guest cabins “Lismer Cottage” [10]. On the occasion of Lismer’s first visit in August of 1921, Merrill wrote to Muriel, “‘Arthur Lismer came up today and I took him out under the Rock...a great artist’s reaction. He looked and looked and could do nothing but gurgle uneffectual [sic] nothings. He is one of the elected because Old Walt silenced his tongue’” [11].

At various exhibitions in 1922, Lismer would show a number of pictures with Bon Echo as their subject. One of his Bon Echo canvases, The Big Rock, Bon Echo [Fig. 4] and its sketch [Fig. 5], are housed in the National Gallery of Canada.

Fig. 4.

Arthur Lismer, The Big Rock, Bon Echo, 1922, National Gallery of Canada, Access. No. 2004

Fig. 5

Arthur Lismer, Study for “The Big Rock, Bon Echo,” 1922, National Gallery of Canada, Access. No. 6117

The composition of these works bear resemblance to the present Bon Echo sketch. Of The Big Rock, Bon Echo, Stacey writes, “The Big Rock[,Bon Echo] is simply there, needing no further emphasis” [12]. As with the paintings in the National Gallery of Canada, in our Bon Echo oil study, Lismer confronts the bluff at lake level. The Rock dominates the majority of the pictorial space, the Mazinaw Lake occupying less than a quarter of the panel with scant cloud forms at right that dip down toward a low horizon. Like its oil sketch counterpart in the National Gallery, Lismer here truncates the Rock, creating the sense that its pitch extends well beyond the confines of the panel. Similarly, the rock shapes of our Bon Echo oil study are, as Stacey describes of the panel in the National Gallery, “built up with shading or bright touches of colour to give them depth” [13].

By varying the consistency of his pigments, using seemingly effortless brushwork and a sonorous palette, Lismer was able to capture both the grandeur and the craggy face of the Rock in this oil study. Heavy-bodied strokes of chartreuse green are dolloped on the panel to suggest both lichen and the ancient gnarled trees that persist, despite the elements, on the cliffside. Strategic dabs of orange, ochre, white, and peachy-pinks dot the surface of the water to indicate the reflection of a gloaming sunlight. Stacey writes of the Rock in such a twilight, "History, legend and archaeology aside, the Bon Echo Rock is an object of impressive grandeur, particularly in the rays of the setting sun” [14].

Stacey, in his conclusion writes, “With the movement of sunlight and shadow, the cliff's multifaceted surface changes in mood and message: it broods, it radiates, it remains, in spite of the levelling forces of frost, rain, snow, wind and, now, acidulation, which chisel continuously at its resisting face. Tenon'd and mortised in granite, a footstep on the larger landscape, quietly it knows the amplitude of time” [15]. He continues, “During the Denisons' time, events at the foot of the silent sentinel travelled far beyond the shores of Mazinaw. Painted images of the Rock made their way into private homes, public galleries and corporate boardrooms. Like the unique features of Algonquin Park and Georgian Bay, the Rock became an icon of 'Northernness,' anchoring an emerging sense of national identity for Canadian artists in search of a new tradition” [16].

Endnotes

1. Robert Stacey & Stan McMullin, Massanoga: The Art of Bon Echo, (Ottawa: Penumbra Press [Archives of Canadian Art], 1998), p.11

2. Ibid.

3. National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives,“Series 16: Bon Echo. – 1980, 1998. – 71 cm of textual records, 1269 photographs, and 685 digital files.“, Robert Stacey fonds: Finding Aid, https://www.beaux-arts.ca/sites/default/files/documents/ngc114(1).html, unpaginated.

4. Robert Fulford, “Scholar was a Group of One; Robert Stacey's love of Canadian art was unique,” The National Post, 12 February 2008, http://www.robertfulford.com/2008-02-12-stacey.html, unpaginated.

5. Robert Stacey & Stan McMullin, Massanoga: The Art of Bon Echo, p. 58

6. Ibid., p. 13

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., p. 58

10. Ibid., p. 15

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., p. 12

15. Ibid., p. 31

16. Ibid.

External Images Cites

Fig. 2. D. Gordon E. Robertson, Pictographs on Mazinaw Rock, Upper Mazinaw Lake, Bon Echo Provincial Park, Ontario, date unknown.

Fig. 3. Photographer Unknown, s.n. [Bon Echo - Old Walt], c. 1919, before 1949.

Fig. 4. Arthur Lismer, The Big Rock, Bon Echo, 1922, Oil on canvas, 91.6 x 101.7 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Accession No. 2004

Fig. 5. Arthur Lismer, Study for “The Big Rock, Bon Echo,” 1922, Oil on wood, 30.3 x 40.8 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Accession. No. 6117

Ajouter un commentaire