Frederick Coburn's "The Green Necklace"

Frederick Simpson Coburn, R.C.A. (1871-1960) The Green Necklace, 1938

oil on canvas, 31 x 25in

Frederick Simpson Coburn is best known for his bright, impressionistic winter scenes depicting teams of horse-drawn sleighs cascading through glistening, opalescent snow. However, an appreciation of Coburn’s oeuvre would be incomplete without consideration of his rare figure studies, which help to illuminate Coburn’s larger significance beyond Canadian Impressionism. One such figure study, The Green Necklace (1938), provides a rare case study of orientalist painting in Canada, helping to answer the question, what might orientalism look like in Canadian art?

It is of no surprise that Coburn may be appreciated across genres. Coburn is among Canada’s first truly international artists, having been instructed in various countries and in various styles and techniques. He was first trained in Montreal at the Council of Arts and Manufactures School, then in New York at the Carl Hecker School of Art and afterward at the Berlin Academy[1]. Coburn then travelled throughout Europe, painting in Munich, Potsdam, Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Salzberg and Leopoldville[2]. In 1982, Coburn enrolled in Paris’ prestigious École Nationale et Spéciale des Beaux-Arts and after three years studying in Paris, he was accepted at the Slade School of Art in London before moving to Belgium, where he met his wife.[3]

Coburn’s success at the Berlin Academy provided him with the recognition required to study in Jean-Léon Gérôme’s small studio at the École Nationale in Paris. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Gérôme is known to have worked quite closely with his students, often even selecting students to complete portions of the master’s own canvases (a hand, a foot). [4]

|

|

|

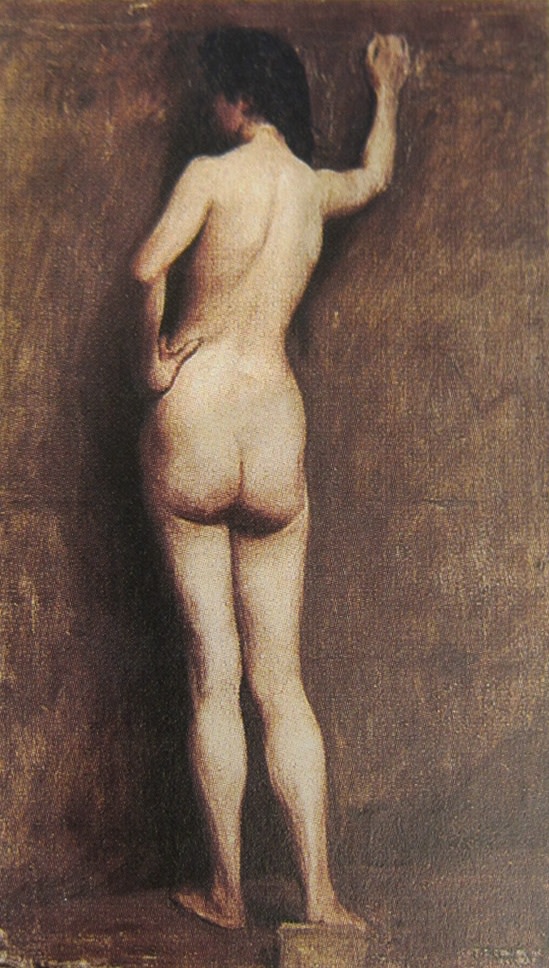

F. S. Coburn Nude Standing, Antwerp, 1901 Coburn Collection. |

Jean-Léon Gérôme Nude from behind, study for king candaule, 1859. Private Collection |

Nearing the end of the 19th century, Coburn’s style was, unsurprisingly, closely aligned with that of his French teacher. A comparison of figure studies by Coburn and by Gérôme demonstrates Coburn’s adoption of academicism, similar to that of Gérôme’s, early on in his career. Completed in 1901, Coburn’s Nude Standing recalls Gérôme’s characteristic approach to modeling wherein figures are rendered in a highly realistic manner using, among other techniques, stronger contrasts of light and shadow.

In The Green Necklace, Gérôme’s influence on Coburn is further made evident by the treatment of Coburn’s own model, the Montreal dancer, Carlotta (born Marguerite Savoie).[5] The seated nude is sensually posed as an Odalisque atop Chinese silks collected by the artist himself.[6] Here, the sitter is grounded in the timeless and placeless exoticism characteristic of the ‘Orient’ in orientalist paintings[7]. However, Coburn creates the orientalist picture without the pseudo-realist, neoclassical style of his master[8]. Gérôme was famously highly academic and vocal in his dislike of Impressionism. By contrast, Coburn, painting three decades after the death of his teacher,rejects Gérôme’s stringent academic approach in favour of a more impressionistic painterly approach in The Green Necklace, painted in 1938.

Further comparison of Coburn to Gérôme makes evident a second important point of distinction in Coburn’s approach to Orientalism, namely in his choice of ornamentation. While Gérôme chooses to orientalize his subjects using motifs from his travels to North Africa, by contrast, Coburn employs Chinese motifs to exotify his sitter. For Gérôme, chinoiserie would have been an unlikely choice of ornamentation because, in the 19th century, chinoiserie would have been more commonly associated with either French Rococo art of the prior century in France or with Modernist movements like Impressionism, which are notably characterized as the break from the Academy.[9] We may then ask why Coburn would elect to recreate a work with all the markings of an orientalist picture, but look to chinoiserie rather than the Algerian or Moroccan sources of inspiration typically associated with the genre (like oriental rugs or tiles).

This conflation of the visual language of orientalism with Chinese material culture reveals that, to Coburn, these Chinese silks must have engendered notions of the ‘exotic other’ akin to those that prompted Gérôme to depict his North African subjects. Put simply, to Coburn, chinoiserie could play the same role in an orientalist picture because it was equally as ‘exotic’ in his mind. This conflation speaks to the contemporary conception of Chinese culture as exotic and ‘other’ in Canada in the late 1930s. At the time Coburn was painting this picture, Chinese Canadians were subject to explicitly discriminatory government policies, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, which restricted their immigration, settlement and ability to work[10]. Nonetheless, while their motifs may differ—Coburn from Gérôme—close analysis of Coburn’s The Green Necklace reveals that similar dynamics of imperial power and privilege are upheld in Coburn’s orientalist work as are so often discussed in Gérôme’s representations of North Africa decades earlier[11].

Coburn’s firsthand connection to the most recognizable orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme must be celebrated. The connection resulted in some of the earliest adoptions of the genre of orientalism in Canada, including The Green Necklace. Rather than consider Coburn’s figure studies as aberrations of Coburn’s long career, these works may be viewed as the culmination of the artist’s French training under one of the world’s most recognizable French painters.

By: Anna Orton-Hatzis

[1] Coburn, Evelyn Lloyd. 1996. F.S. Coburn: Beyond the Landscape. Erin, Ont.: Boston Mills Press, 28.

[2] Ibid, 34.

[3] Ibid, 40.

[4] Ibid, 35.

[5] Robinson, Jody. 13 April 2010. “Behind the Lens: F.S. Coburn and Dance,” Sherbrooke Record.

[6] Coburn, 100.

[7] Please see Linda Nochlin’s canonical text The Imaginary Orient to read more about the characteristics of Orientalist paintings by Jean Léon Gérôme.

[8] Gérôme’s style is further described in "The Imaginary Orient," on page 37.

[9] In the 2013 book A Taste for China, author Eugenia Jenkins has even argued that chinoiserie may not simply be considered another form of orientalism, the appropriation of East by West, but rather instead it’s influence was more similar to a cultural exchange: “chinoiserie in literature and material culture played a central role in shaping emergent conceptions of taste and subjectivity [in England]”.

[10] Ibid.

[11] To read more about orientalism in Gérôme’s work I again recommend Linda Nochlin’s The Imaginary Orient.

To read more about orientalism broadly, I recommend Edward Said’s foundation book Orientalism (1978) New York: Pantheon.