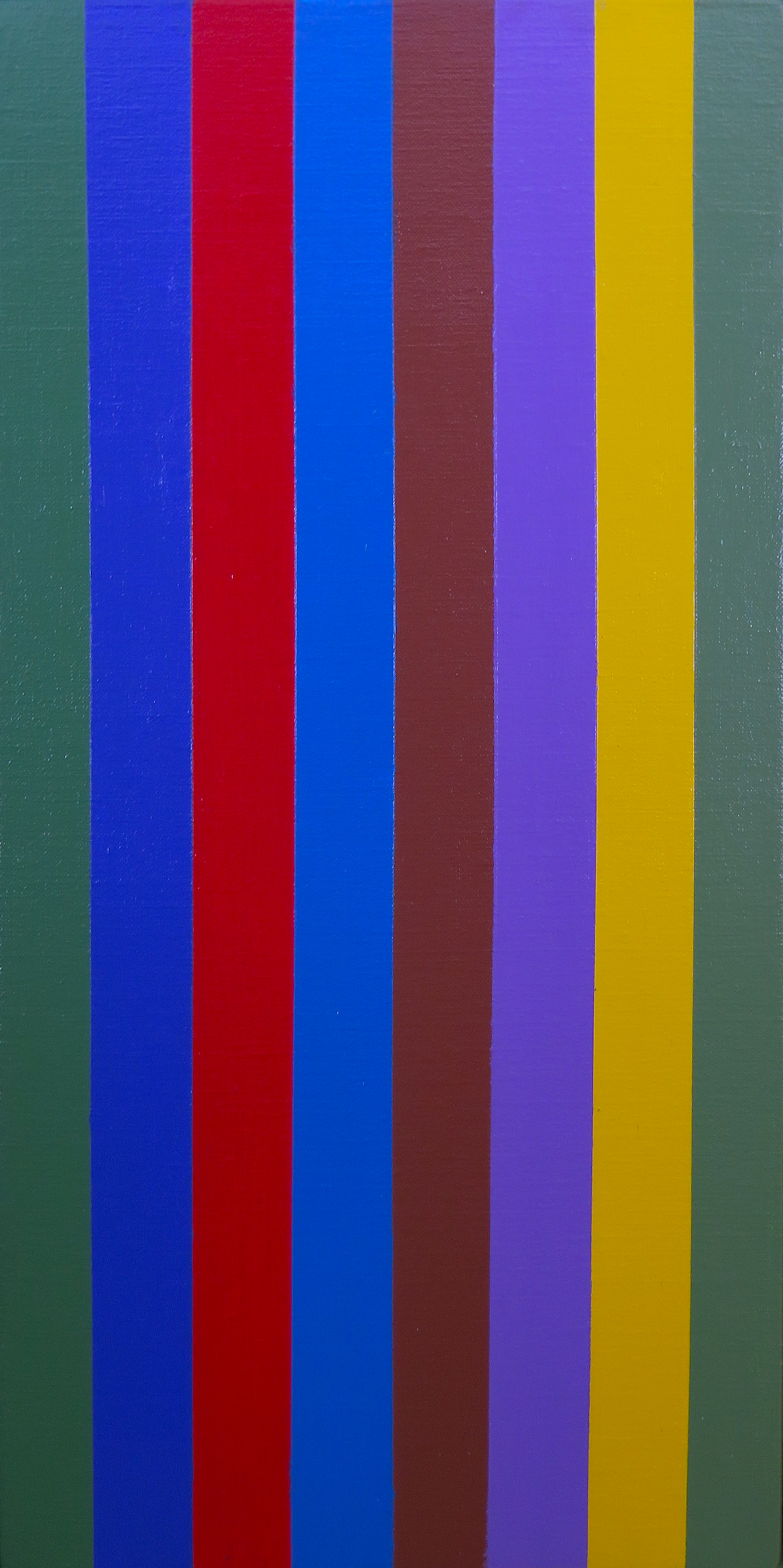

Molinari Stripe Painting A Source of Pure Joy

Guido Molinari, O.C. R.C.A. (1933-2004), Untitled, 1968

acrylic on canvas, 20 x 10 in.

On display at our Toronto Gallery through September, 2015.

Guido Molinari is famous for his vertical band paintings. This one, dated 1968, is from a series that occupied him during the sixties. What is less known is what prompted him to adopt this vertical format, the complete elimination of the horizontal, and the absence of any suggestion of depth in his painting. To answer these questions, one has to contrast Molinari’s approach to painting with the kind of abstract painting developed by Borduas and the Automatistes. Consider, for instance, a typical automatiste painting by Borduas, like 8.47 or Carquois fleuris, 1947.

Paul-Émile Borduas, 8.47 or Carquois fleuris, 1947, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 109.2 cm. Coll.: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (since 1962; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Maurice Chartré).

As the title of the work implies, we are confronted with a series of “flowered quivers,” suspended in space in front of a background which seems to recess indefinitely behind them. Not only is depth strongly suggested but this is done by the horizontal bands one above the other in the background. Moreover, if we compare the colours in both paintings, Borduas seemed more attracted by shades (tons rompus) than by purer colours like Molinari.

In a famous debate around the exhibition Espace 55 (organized by the critic and gallery owner, Gilles Corbeil), which took place in February 1955 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Fernand Leduc was accused by Borduas of going back to geometric abstraction, which in his eye was “archaic”, when compared to the American paintings of Jackson Pollock or Franz Kline, where freedom was given to the “taches" (spots) in an infinite space. Molinari entered the debate with his famous text titled, L'Espace tachiste ou Situation de l'automatisme (The Tachiste Space or The Situation of Automatism), where he said that it was the derivation from the surrealist conception of pictorial space that made the Automatists “dépassés" (obsolete). Indeed, the Surrealists (Dali could be a major example), were not interested in renewing the conception of space, but kept all the conventions of perspective, what Molinari called the “Euclidian space,” alluding to the Euclidian geometry pervasive during the Renaissance. For Molinari, the Surrealists constituted a kind of parenthesis in the development of modern art. By going back to geometry, to flatness (bi-dimensionality) and pure colour, the Plasticiens and he were in fact resuming the evolution of modern painting after Cubism and bringing it even further ahead.

In his own development, Molinari gave a crucial importance to his reading of a letter by Piet Mondrian, dated 1943, which was quoted in an article by James Johnson Sweeney and published in Art News in the summer of 1951. Mondrian claims that he tried to destroy what was contradictory in his work: first the cubist space, then the plane, then after his moving to New York, the black lines in order to reach a greater dynamic equilibrium. Molinari was very impressed by the fact that this “principle of destruction” was "the main dialectical force in the concept of evolution towards a new space". He said to the curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Roald Nasgaard: "This was a main event in my life, the discovery of Mondrian’s letter, his self-critique, and his repudiation of his own past." So little by little, Molinari, following Mondrian's example, eliminated depth, then the idea of a hierarchy between the elements in his painting, then any suggestion of a horizon, then shades, to achieve finally a perfectly bi-dimensional space and pure colour. The painting suggests proximity to the onlooker and doesn’t create the illusion of a distant background like in a classic painting of the Renaissance. As the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze has proposed: the space expressed then in a painting of this type is smooth (“lisse”), not striated (“strié”). In a picture like, for instance The Annunciation, circa 1472-1475 by Leonardo da Vinci, the Angel and the Virgin belong to one ridge (or stria); the wall of the garden, to another one; the line of trees to a third one; and maybe it is necessary to add two more to accommodate the mountains in the background. This striated space is very efficient to convey the distant, and the far.

Leonardo da Vinci, Annonciation, c. 1472‐1475

oil and tempera on pannel, 98 x 217 cm. Coll.: Uffizi, Florence.

But in a painting like Untitled, 1954 by Molinari, we are in a proximate space, reachable by hand, so to speak. Even the fact that the impastos are quite strong encourages this type of reading. There is no more a succession of striae in depth, no more a suggestion of remoteness. Everything seems à la portée de la main (at hand). That is why Deleuze speaks of an “espace lisse (a smooth space)”.

Guido Molinari, Untitled, 1954, oil on canvas, 19.75 x 24 cm (7.7 x 9.4 in).

This is exactly the type of space we have in our painting of 1968. The vertical stripes are not perceived superposed one behind the other, but juxtaposed one to the other. A “reading” from left to right, and right to left is the best way to perceive it.

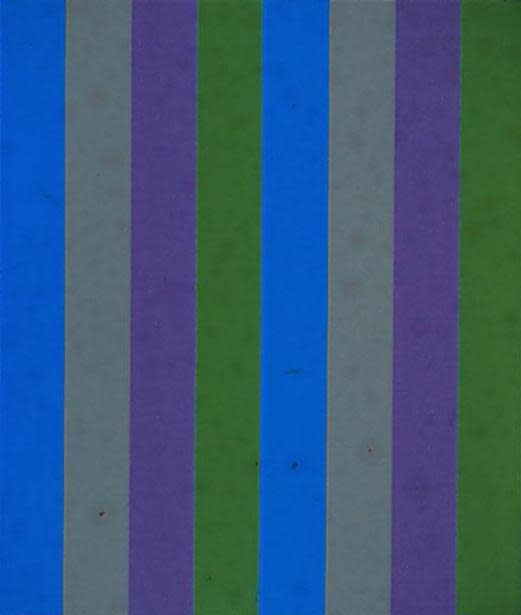

If we compare it to an early vertical band, like Sériel bleu vert, 1958, two elements have changed: 1) the colours of the bands are much less saturated than in our painting (except the blue and the red); and 2) the idea of repetition of the sequence of the colours, like here, from left to right: blue, grey, violet and green is abandoned, announcing the future development of Molinari's painting. The colours can be appreciated for themselves and are more varied than in the previous paintings.

Guido Molinari, Sériel bleu vert, 1958, acrylic on canvas, 177.8 x 152.4 cm (70 x 60 in). Coll.: G. Molinari Foundation.

With Molinari, painting is about painting, and a source of pure enjoyment.

We thank François-Marc Gagnon, O.C., Ph.D. for this appreciation. Dr. Gagnon is the Founding Director and Distinguished Research Fellow of the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art. He taught at the Université de Montréal for thirty-five years and was a lecturer in Concordia’s graduate art history program. Dr. Gagnon received the Governor General’s Award for his 1978 critical biography of Paul-Émile Borduas. He authored numerous books, monograph studies and essays for exhibition catalogues and has curated a number of these exhibitions. He is also the author of the Catalogue Raisonné of the oeuvre of Paul-Émile Borduas.