Art canadien classique

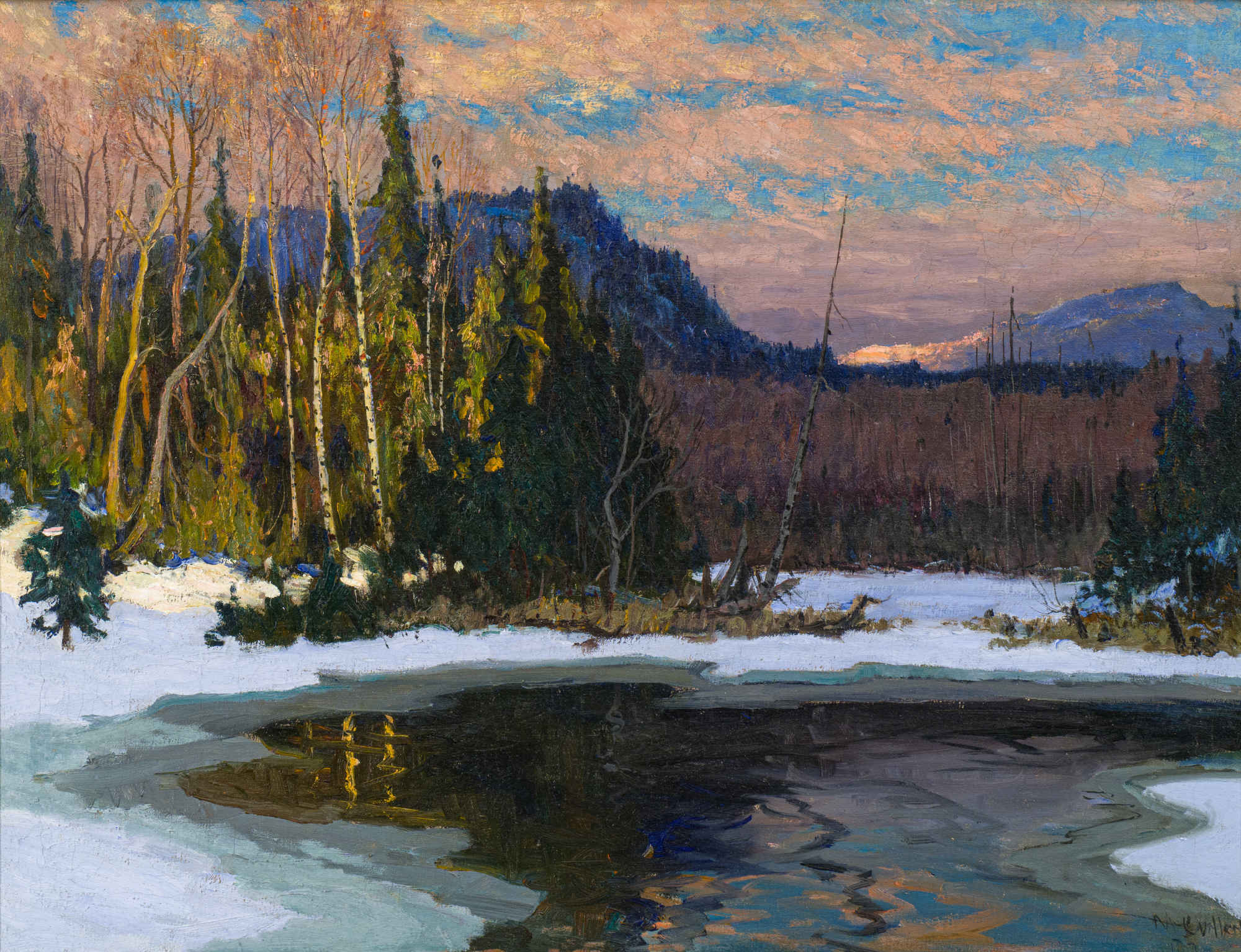

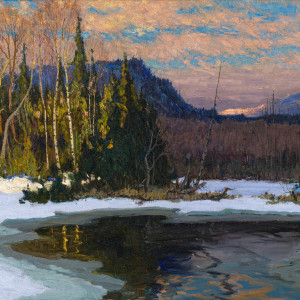

The Devil's River near Mont-Tremblant, 1931 (circa)

61.6 x 81.9 cm

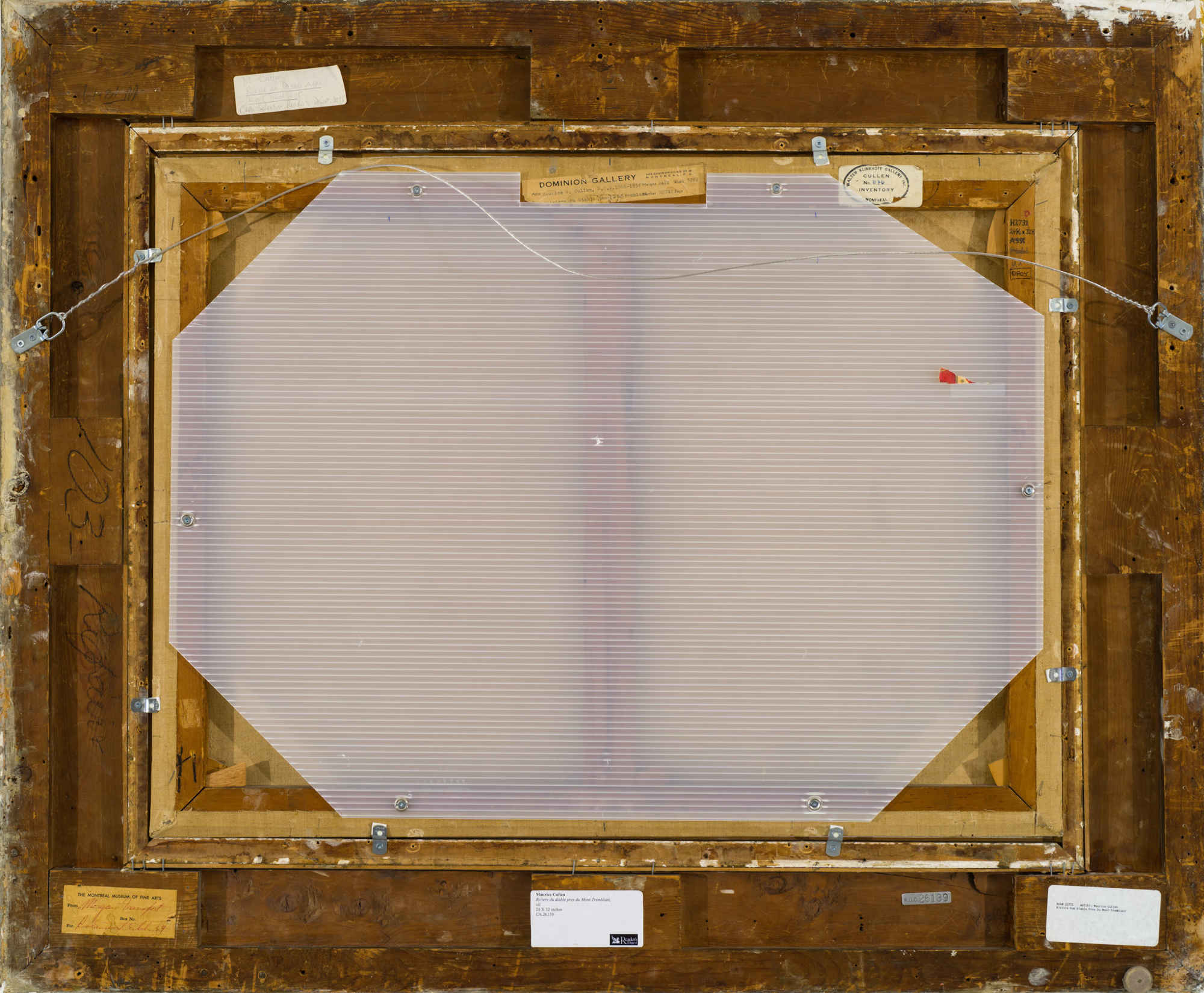

Alan Klinkhoff Gallery Cullen Inventory No. AK1176

Walter Klinkhoff Gallery Cullen Inventory No. 1176

Inscriptions

signed,’ M. Cullen’ (lower right)Provenance

Watson Art Galleries, Montreal

Dominion Gallery, Montreal, Inventory No. H2742

Reader’s Digest, Canada Ltd., Montreal, Collection No. 26139

Heffel Fine Art Auction House, Fine Canadian Art, 24 November 2005, lot 60

Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc., Montreal

Expositions

Kitchener, Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, Maurice Cullen, 6-17 January 1965, cat. no. 5.Laval, Fondation de la Maison des Arts de Laval, Couleur et lumière : les paysages de Cullen et de Suzor-Coté, 22 November 1991, cat. no. 25.

Documentation

Louise Beaudry, Couleur et lumière : les paysages de Cullen et de Suzor-Coté (Montreal : Fondation de la Maison des Arts de Laval, 1991), 25 [reproduced], 39.

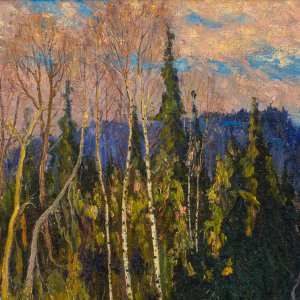

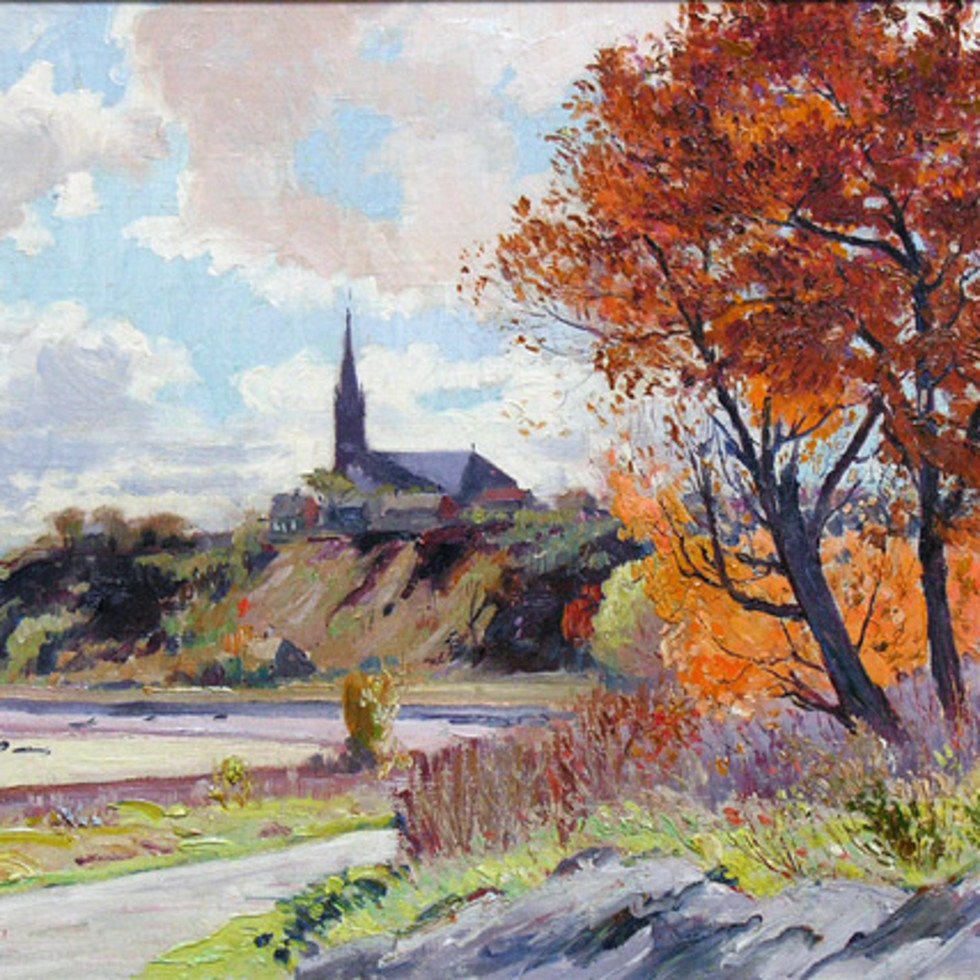

William R. Watson, a Montreal gallerist who became Maurice Cullen’s dealer in 1923, once recounted that when asked what he required for an ideal life, Cullen claimed all he wished for was “A studio of my own, a shack in the mountains, a garden for an acre of flowers…and a heavy snowfall every winter.”[1] Late in his career, at a time when his paintings were finally attracting significant commercial as well as critical interest, Cullen built a cabin at Lac Tremblant, a lake connected to the Cache River and the Devil’s River. Although he visited the area for the first time in 1912, the larger part of his work there is associated with the period from the early 1920s to the early 1930s. [2] At that time he spent part of each year there, often the winter and early spring, seeking out subjects on snowshoes and canoe excursions. [3] Winter on the Cache River; Spring, Caché River; The Devil's River near Mont-Tremblant [the present work]; and Early March on the Cache Rivière all date from this period, and they are among numerous oil paintings and pastels that depict the area.

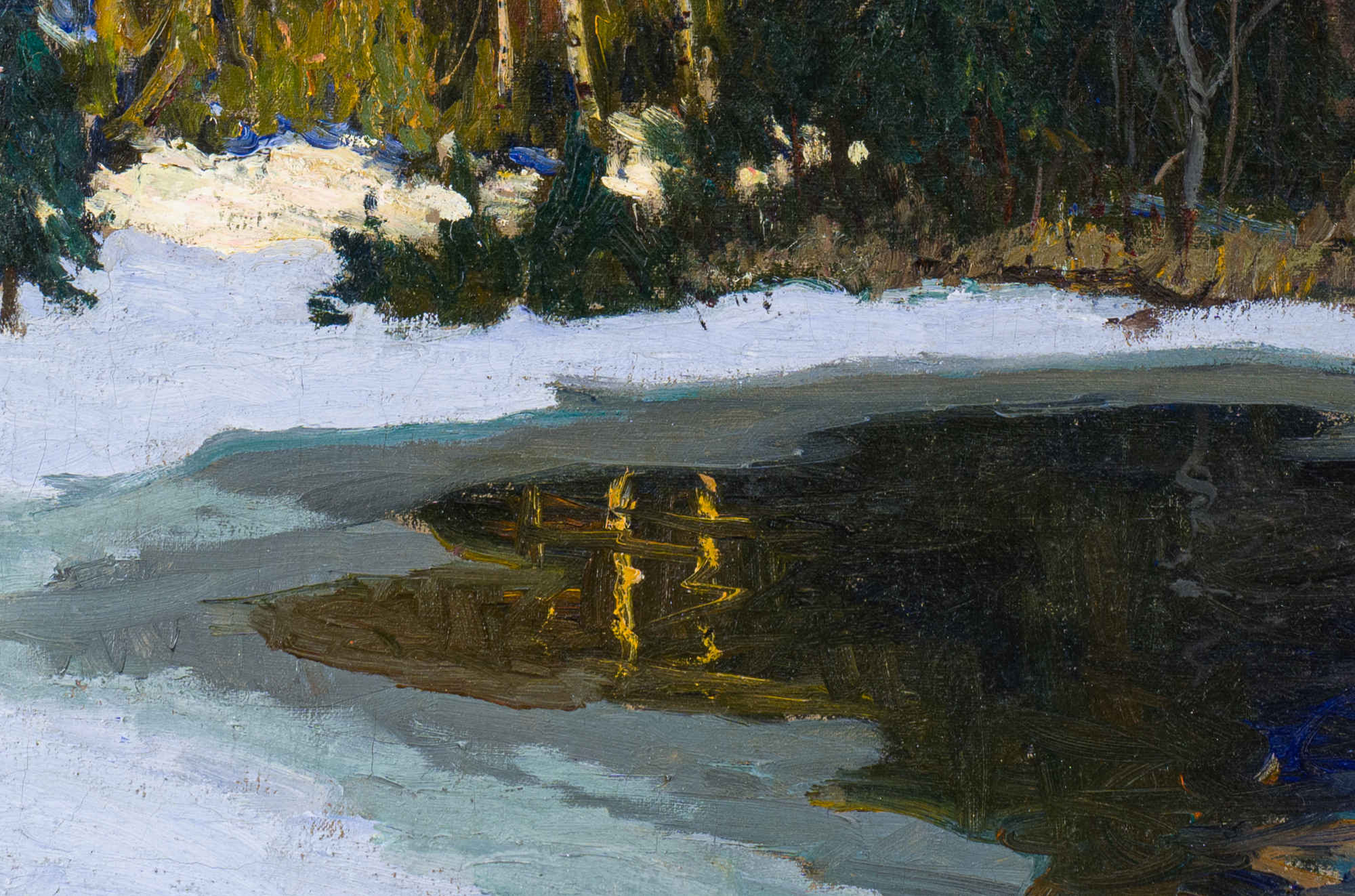

All these works most likely began as plein air sketches. Cullen’s commitment to studying snow and ice was such that since the mid 1890s, he had often chosen to work on his winter compositions outdoors, no matter how cold it was. Robert Pilot (1898–1967), his stepson, recalled that in order to do this he “used on his painting hand a heavy wool sock with a hole through which to insert the brush. He felt that the “Feel” of the brush was lost by using gloves.” [4] Another challenge was the paint itself: at sub-zero temperatures, it would become stiff and difficult to work with; Sylvia Antoniou has suggested that this might be one reason that Cullen often painted his snow impasto, and this may have influenced elements such as the bold blue shadows in Spring, Caché River. [5]

These compositions also share a similar tone and atmosphere. Many of Cullen’s images of the Cache River might be described as meditative in that they often appear to capture the river in still, peaceful moments. Watson visited the river with the artist, and his account of the experience emphasizes Cullen’s attraction to the quiet. He asked Watson to remain silent as they paddled, and, in Watson’s words, “The waveless, winding stream, the heavy peace of silence and solitude, and the mystery given by dusk. To Cullen this might well be a sacred stream […] You will understand why, in these pictures of the Laurentians, Cullen never introduces a figure, but leaves you to contemplate the landscape without company. [6] With Winter on the Cache River and The Devil's River near Mont-Tremblant, Cullen positioned his viewers practically on the water, as if to share his intimate experience of nature with us.

Cullen’s paintings of this region became some of his most successful works, appearing regularly in exhibitions from 1920 until his death in 1934. Many attracted critical attention; for instance, in 1930, when Cullen had a solo show at Watson’s gallery, Samuel Morgan-Powell claimed that “he has painted some of his finest canvases” in the region around Tremblant, promising readers that “You feel the Laurentian atmosphere; you revel in the sheer loveliness of tone. You sense the tang of the winter air, and the fascination of ice and snow seen under varying conditions of light is ever-present.”[7]

By the late 1920s, Cullen’s Laurentian landscapes were selling very well, bringing him unprecedented income that allowed him to travel, and to build a new studio. [8] While the majority went to private collectors, there were also notable institutional acquisitions: the province of Quebec bought Le Printemps, rivière Cachée, 1920, in 1920 (today the work is held by the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec); the National Gallery of Canada bought Sunrise, Lac Tremblant, 1922, in 1925; and the Art Association of Montreal purchased The North River, 1932, in 1932. Reflecting on the success of his paintings of the Cache River, Cullen remarked “Well, perhaps, I’ve brought fame to one little river.” [9] He had also confirmed his own status as one of the most celebrated winter painters in the history of Canadian art.

Jocelyn Anderson

Jocelyn Anderson is the Deputy Director of the Art Canada Institute. Her research focuses on Canadian art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and more broadly on landscape imagery in the British Empire. She is the author of William Brymner: Life & Work, as well as essays for a number of periodicals including British Art Studies and the Oxford Art Journal. She holds a PhD from the University of London (Courtauld Institute of Art).