-

Artworks

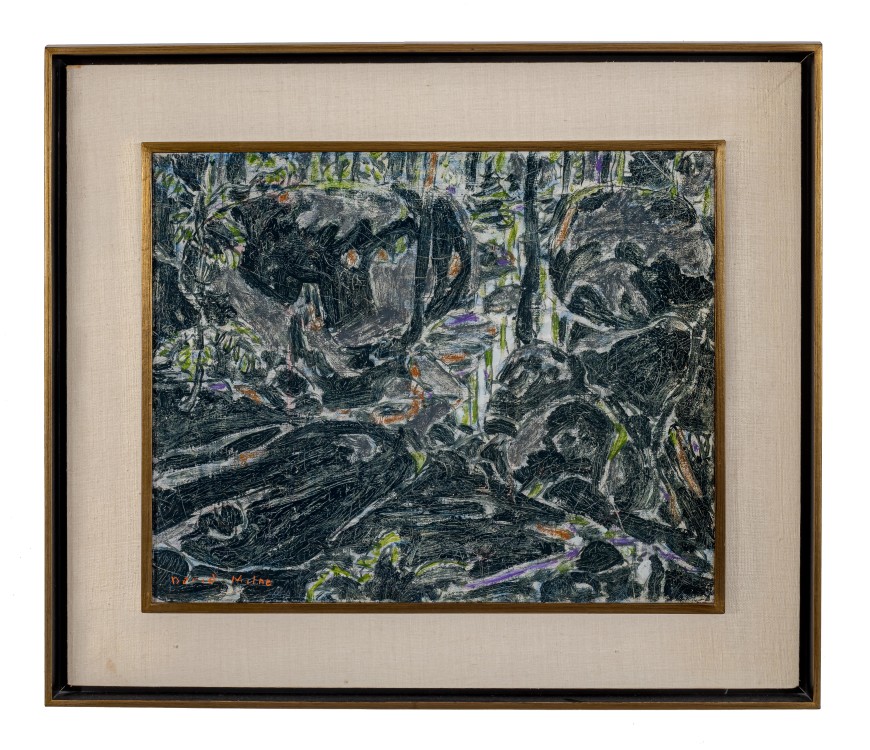

David MilneStream in the Bush (Boulders in the Bush II) (Big Moose Lake, Adirondacks, New York), 19261881-1953Oil on canvas16 x 20 in

40.6 x 50.8 cm

This work is included in the David B. Milne Catalogue Raisonne of the Paintings compiled by David Milne Jr. and David P. Silcox, Vol. 1, no. 207.78.SoldInscriptions

signed in 1946, ‘DAVID MILNE’ (lower left)Provenance

Galerie Godard Lefort, Montreal.

The Collection of Mitzi and Mel Dobrin.

Peter Bronfman, Toronto, 1971.

Waddington Galleries, Montreal, 1977.

Purchased by unknown owner, 1977.

Galerie Bernard Desroches, Montreal, 1980.

Dominion Corinth Galleries Ltd., Ottawa as Black Boulder by the Stream.Exhibitions

Montreal, Galerie Godard Lefort, David Milne (1882-1953) : a survey exhibition, April 22-May 15, 1971, no. 12.

Literature

Galerie Godard Lefort, Montreal, David Milne (1882-1953) : a survey exhibition, April 22-May 15, 1971, no. 12.

Kirkman and Heviz, 1971.

White 1971.

Galerie Bernard Desroches, 1980, repr. p. 8, as Black Boulder by the Stream.

David Silcox, 1996, Painting Place: The Life and Work of David B. Milne, University of Toronto Press, p. 191.

David Milne Jr. and David P. Silcox, David B. Milne: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings Volume 1: 1882-1928, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), no. 207.78, reproduced p. 430.

"The stream noted in the title...is a tour de force of observation and subtlety."

-Mark A. Cheetham

Stream in the Bush (Boulders in the Bush II) is an exceptionally complex and accomplished painting. It is the fruit of what Milne described regarding another work of the same year as his “inventory method,” that is, a discipline through which he limited his view radically and then focused intently on everything he could see. Each element receives equal attention, with the result that even today, after over a century of familiarity with abstract art and all manner of artistic experimentation, it takes a moment to orient oneself in this picture. Milne asks us to look as hard and long as he does. We discern a forest with trees, foliage, boulders, and water, all in flux, it seems, because of the glinting light that he characteristically indicates with untouched or minimally painted passages and with coloured highlights across the canvas surface. The oil paint is thin, scraped and scarred in concert and sympathy with the boulders themselves. The stream noted in the title (an orienting description added by the authors of the Milne Catalogue Raisonné, not Milne, because the image is cognate with another that Milne does title with this element), is a tour de force of observation and subtlety. We might not immediately see this stream; its course and tributaries can be read in many ways. Water is suggested at the centre right with an open area of canvas only minimally tinged with blue. Looking more closely, we see that this must be a reflective surface: the interrupted green trunks of the trees appear to be partial mirror images of the trees we see along the upper perimeter of the painting. Water could also flow between the boulders, functioning for Milne as both a theme and a dividing feature between the rock formations.

Milne has looked long and hard at this intimate, initially disorienting, scene. Yet the thin pigment and daubed highlights suggest that he painted it quickly. In a letter from about the time this painting was done, he claimed that “quickness of execution is important.” The resulting immediacy guaranteed the authenticity of vision for artist and viewer alike. He believed that speed in both execution and a viewer’s apprehension heightened the emotional effect of the work, which was for him all important. Milne claimed that “Feeling is the power that drives art. There doesn't seem to be a more understandable word for it, though there are others that give something of the idea: aesthetic emotion, quickening, bringing to life. Or call it love; not love of man or woman or home or country or any material thing, but love without an object - intransitive love.”

The quickness, minimal pigment, and incised lines that we see on the boulders especially in this oil painting suggest its affinities with another medium in which Milne excelled, drypoint, a method similar to engraving except that the lines are carved into the plate rather than bitten with acid. Milne was familiar with this print technique from his student days. Always a technical innovator, in the early 1920s especially he extended what was historically this very restricted, one-colour medium to one that displayed full colour. He returned to drypoint on and off in his subsequent work.

Looking at the painting alone, it would be difficult to know just where Stream in the Bush was painted. We also need to ask whether locale is important to our appreciation of the work, given that Milne was unconcerned with national associations in landscape. Yet it is both interesting and germane to follow Milne’s career through the many areas in which he lived and worked. It’s also pertinent to note that he was almost always impecunious; his work was rarely painting in the first instance, though of course he would have had it otherwise. He was constantly worried about securing materials and selling his work. It’s often noted in the literature on Milne that he rarely painted large works. Milne’s aesthetic preferences and a certain modesty are cited as reasons, but we should also keep in mind that smaller works using inexpensive pigments were less expensive to buy. Given these circumstances, it is all the more remarkable that Milne was such a productive and thoughtful artist. It was his ambition to publish a full account of his art practice and thinking about aesthetic issues.

From 1924-1929, Milne and his wife Patsy lived in upper New York State, in Lake Placid in the winters and Moose Lake, about 150 kilometers distant, in the summers. Twice hosting the Winter Olympics (in 1932 and 1980), Lake Placid was from the late 19th century a year-round vacation destination for the elite of the Northeast USA. The Milnes ran and lived in a tea house at a Lake Placid ski resort, pictured in Ski Jump and Tea House, Lake Placid of 1925. Milne was aware that the patrons of the Lake Placid tea house were less than receptive to the paintings he showed them, finding them too radical. At Moose Lake the Milnes also ran a summer teahouse; there Milne also built a larger house that they sold in 1928 when the couple moved on. In this roughly five-year span, then, economic exigencies kept Milne from painting much of the time, yet what he produced – as witnessed by Stream in the Bush and an outburst of related paintings – was intense and memorable. Milne was an explorer of the intricacies of what he saw, not an adventurer who sought new and purportedly wild landscapes in the Group of Seven mold.

Mark A. Cheetham

Notes:

Duncan gave the title Stream in the Bush to this painting and to a drypoint (Tovell 55) that derives from Trickling Stream, 207.77, and not from this subject. Milne titled the impression of the drypoint he sent the Masseys Stream in the Bush - Big Moose. See Boulders in the Bush I, 207.76. for comment. - Catalogue raisonné (Silcox, Vol. 1, p. 430).