-

Artworks

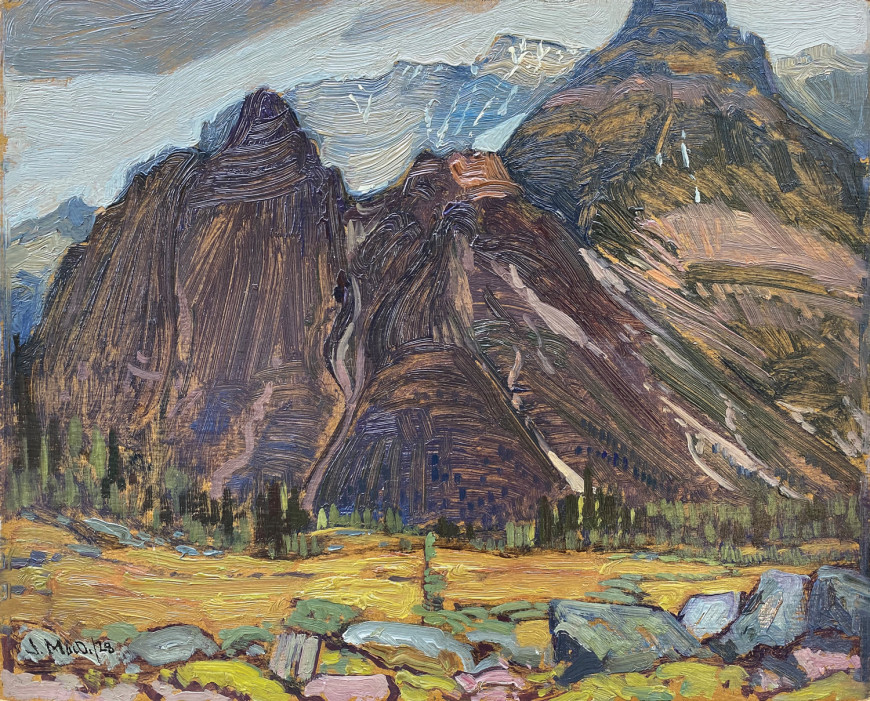

J.E.H. MacDonaldWiwaxy Peaks, Lake O'Hara Camp, 1928 (September)1873-1932Oil on board8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in

21.6 x 26.7 cmSoldInscriptions

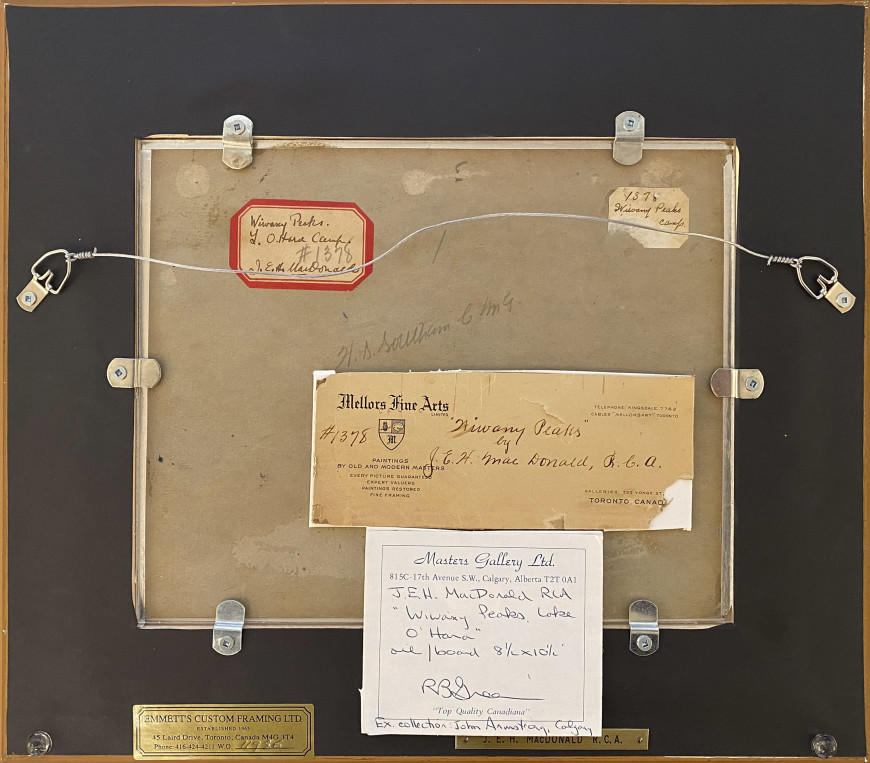

signed and dated, ‘J.MacD.\28’ (recto, lower left); signed and inscribed on artist label ‘Wiwaxy Peaks. / L. O.Hara Camp. / #1378 / J.E.H. MacDonald’ (verso, upper left); inscribed ‘H.S. Southam CMG’ (verso, center)Provenance

Mellors Fine Arts Limited, Toronto.

Collection of H.S. Southam.

Collection of John Armstrong.

Masters Gallery Ltd., Calgary;

Private Collection, Arizona, U.S.A.

This charming and energetic work comes from 1928, a banner year at Lake O’Hara. -Lisa Christensen

— James Edward Hervey MacDonald’s Lake O’Hara sojourns are great pilgrimages in the annals of Canadian art history. From the first time he visited and painted the region in 1924, he was obsessed, and henceforth until his death in 1932, painted there almost exclusively. His son Thoreau recalled that his father wished to talk of nowhere else upon return from sketching there each year. As David Milne fixated on Boston Corners, so MacDonald was fascinated by Lake O’Hara.

This charming and energetic work comes from 1928, a banner year at Lake O’Hara. That summer, climbers Georgia Engelhard and Ernest Feuz made an attempt on Mount Hungabee, and Mary Walcott of Burgess Shale fame, Jim Brewster, and photographers Henry and George Vaux all stayed at Lake O’Hara Lodge. In July, fellow Group of Seven painter Lawren Harris and his sons Lawren P. and Howard, along with Mrs. Harris, as well as the Group’s Arthur Lismer and his wife Marjorie Lismer all signed into the guest registry. Fred Niven, painter, and author of Colour in the Canadian Rockies (one of the first guidebooks to the Canadian Rockies), and painters Fred and Bess Housser visited in August. When MacDonald arrived on September 1st for a stay of almost three weeks, it was as if the A-List of Lake O’Hara’s historical names had convened. It was also the year MacDonald would meet Tommy and Adeline Link, and Banff’s own Peter Whyte, forming rich friendships with them. Thus, MacDonald was surrounded by the stimulating conversation of like-minded individuals, wherein rich ideas were shared and companionable groups set out together to sketch, photograph, and picnic in the beautiful hanging valleys that cradle the lake. These conditions, combined with the richly gilded fall colours of this glorious time of year in the Canadian Rockies resulted in some of his finest mountain works.

This work depicts the distinctive silhouettes of the Wiwaxy Peaks, shown as a backdrop to the high alpine meadows of the Opabin Plateau. This was MacDonald’s favourite O’Hara haunt. After following the Alpine Club’s horse trail up the side of Opabin Creek, he reached a wide hanging valley, dotted with small lakelets and strewn with wildflowers. The valley is ringed with large boulders, time tumbled from the peaks nearby, and now covered in green and yellow crust lichens, visible in their distinctive colours in the near ground of this work. There is no indication that a steep valley cradling Lake O’Hara lies between the meadow and the distant peaks, a trickster-esque perspective that MacDonald often used – we are at over 2,200 meters of elevation here. Only the north ridges of Mount Victoria that rise behind Wiwaxy’s ridgelines tell us how high up we are in the mountains. The lowest col is Wiwaxy Gap, a stiff climb that takes you to an eagle’s aerie view of the valley and peaks beyond.

MacDonald’s affection for Lake O’Hara is apparent in this fine work, while the distant cloudy weather gives way to sunshine and the Wiwaxy Peaks glisten, perhaps wet from rain, we feel welcomed into an idyllic scene. Despite the celebrity contingent visiting the area, 1928 saw a year of poor weather for O’Hara, which did not daunt, in fact it served to delight MacDonald, creating contrasts of colour by adding the whites of snow and the varieties of grey-clouded skies to his palette. On September 15th, when he climbed to the Opabin Plateau meadows - to a place he referred to as “the old spot” - he made notes in his journal, describing a “Very clear morning and snow brilliant on peaks... a perfect silence at the old spot when the wind fell, the brilliant clouds moving slowly among the peaks... A perfect day, and then a little dropping of hail, hinting at more to come.” He found the rapid changes in light and colour a fascinating challenge rather than a frustrating factor, marking again his complete delight with the western landscape. While many other mountain painters complained of these things in their journals, diaries and letters, MacDonald revelled in them, as the calligraphic brushwork, harmonized notes of colour, and inviting composition tell us. He continued in his journal... “So I left with the birds (though not so lightly). Glad to come and glad to go and went off down the trail...”

Lisa Christensen

_________

MacDonald Journals, Vol. 1, file 1-10, 1928, pp 9-10. National Archives of Canada