-

Artworks

Emily CarrHaida Totem, 19281871-1945Oil on canvas36 x 18 in

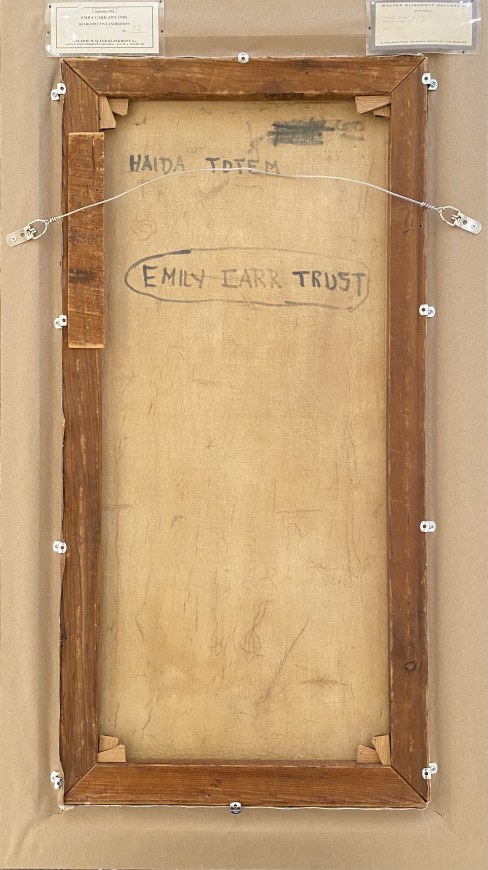

91.4 x 45.7 cmSoldInscriptions

signed by the artist, ‘M. EMILY CARR.’ (lower right); photo of verso of canvas before lining, ‘HAIDA TOTEM / EMILY CARR TRUST’ (verso, upper left on left stretcher bar); inscribed on section of original stretcher, ‘62B / 36 ½ x 17 ½ / 6300’ (verso, upper right on right stretcher bar)Provenance

Acquired from the artist by Dominion Gallery, Montreal, August 1944.

Private collection, Montreal, 20 November 1945.

Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc., Montreal;

Acquired from the above by Mitzi and Mel Dobrin.

Exhibitions

Montreal, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, Emily Carr (1871-1945) Retrospective Exhibition, 14 - 28 September 2002, cat. no. 22.

"...in these paintings Carr gave up her concern for painterly surface and started to translate what she saw in nature into three dimensional hard-edge forms."

-Charles C. Hill

- Emily Carr was one of Canada’s most innovative artists of the first half of the twentieth century. After periods of study in San Francisco, England and France, in 1912 Carr made a major trip to Alert Bay, the Skeena River and Haida Gwaii visiting Kwakwaka’wakw, Gitxsan and Haida villages. The following April she organized an exhibition in Vancouver of nearly 200 paintings and watercolours of the monumental arts, heraldic poles and houses, of these and other First Nations of the Pacific Coast, interpreted in the fauvist style she had learned in France. Following the exhibition Carr returned to her hometown of Victoria where she had built a house the rental income of which was to provide financial backing for her to continue her travels and painting. But, in fact, the return was the beginning of a fourteen-year hiatus in her career when she almost stopped painting.

In her book on Emily Carr, published by Douglas & McIntyre in 1990, Doris Shadbolt provided the most in-depth study of Carr’s development during the second period of her career. In December 1927 Carr’s paintings from 1912 and 1913 were included in the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art Native and Modern at the National Gallery of Canada. The exhibition provided Carr with the opportunity to travel to Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto where she met the members of the Group of Seven. Three visits with Lawren Harris provided her with a new faith in her work and a new mission and she returned to Victoria with memories of Harris’ paintings in her mind.

Since her return from France, Carr had consistently worked from studies painted in the field and, having no new material, she now worked from watercolours she had made prior to 1913. As she wrote to Marius Barbeau, ethnologist at the National Museum in Ottawa on 12 February 1928, “I have been working at some of my Queen Charlotte Is[lan]d sketches there is quite a difference in the character and coloring to the mainland poles, in the Q[ueen] C[harlotte] Is[land]s. They are greyer and more sober and desolate and tragic. I love them.” And on 9 March she wrote to Eric Brown, Director of the National Gallery, “I am … using gallons of paint these days, and lots of canvas. I am perfectly thrilled at working at the Indian stuff again, and I really don’t know half the time if I am here, or in the northern villages, when I get working on those old sketches.”

In the spring of 1928 Carr painted two canvases of a mortuary pole she had first sketched in the village of Skidegate on Haida Gwaii in 1912. The 1928 canvas Skidegate in the Vancouver Art Gallery (42.3.48) closely follows the composition of the 1912 watercolour (figure 1). The pole faces right and she has included the peaked roofs of the houses that cut the pole off below the lower dorsal fin. A 1912 oil, Mortuary Pole, Skidegate, in the Vancouver Art Gallery (figure 2) depicts the same pole facing left, and includes the double finned killer whale at the base and a fence and trees behind. This canvas was undoubtedly painted by Carr from a currently unlocated watercolour of 1912. The larger 1928 canvas, Haida Totem from the Dobrin collection, also depicts the full totem from the base to the grizzly bear crest on the front plaque but the pole faces right and Carr has changed the modern peak roofed houses for a traditional, communal house behind.

As Shadbolt observed, in these paintings Carr gave up her concern for painterly surface and started to translate what she saw in nature into three-dimensional hard-edge forms. The background is still treated as a decorative backdrop but the surface is smooth, forms are simplified and the muted colour is determined by the depicted objects. The leafless vertical tree spars and simplified background trees are reminiscent of Harris as is the treatment of the sky. Developing her new formal language Carr would return to the Skeena River and Haida Gwaii (and travel to the Nass River for the first time) in the summer of 1928.

Charles C. Hill, C.M.

Note:

Emily Carr’s letter to Marius Barbeau is in the Marius Barbeau fonds, Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau; to Eric Brown in the Library and Archives, National Gallery of Canada. Harris’ letters to Emily Carr are in the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria