-

Artworks

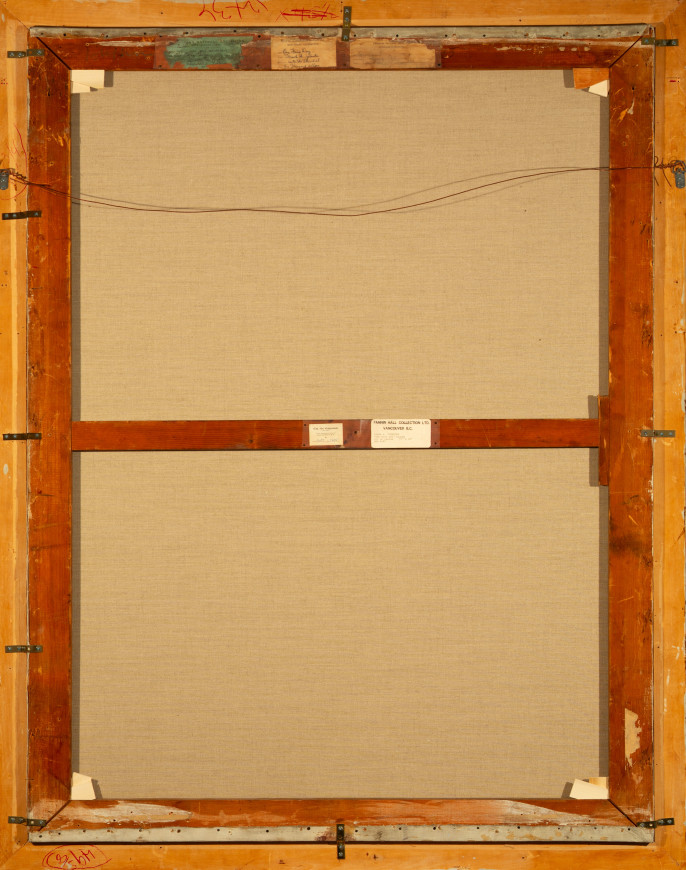

Francis Hans (Frank/Franz) JohnstonTribute to Tom Thomson, 1923-1925 (circa)1888-1949Oil on canvas57 x 42 in

144.8 x 106.7 cmSoldInscriptions

signed, ‘Frank H. Johnston’ (lower left)Provenance

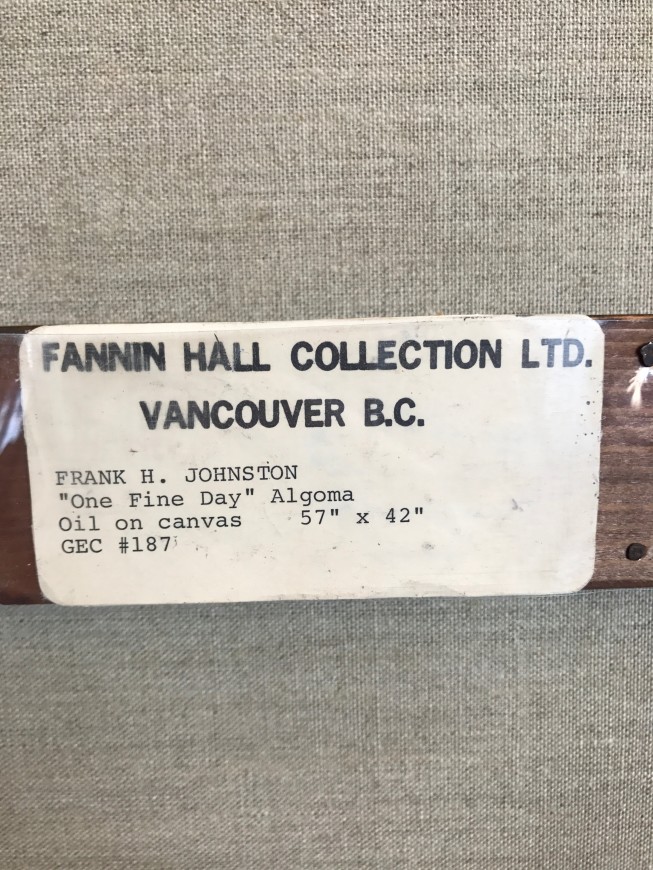

Fannin Hall Collection Ltd., Vancouver.

The Art Emporium, Vancouver, 1973;

Acquired from the above by Mitzi and Mel Dobrin, circa 1980.

Exhibitions

Vancouver, Kenneth Heffel Gallery, Second Annual Group of Seven Exhibition, 3 March, 1980, as One Fine Day, Algoma.

Literature

"It was one fine day when this show opened its doors", Larry Emerick, Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, BC), 3 March 1980, B5, illustrated with a photograph by Ralph Bower, Roaslyn Porter looking at One Fine Day by Frank Johnston: "Frank Johnston, another favorite, provides one of the blockbusters of the exhibition with One Fine Day, Algoma."

Frank Johnston got his real start as an artist when he worked at Grip Limited in Toronto in 1911. At this lively, highly competitive commercial art firm, he met future Group of Seven members J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, and Franklin Carmichael. There is no record of his meeting Tom Thomson but both were at Grip at the same time. Likely they spoke or, at least, had a nodding acquaintance.

Doubtless, Johnston would have watched Thomson go on his painting trips (which began in 1912) with envy as he continued to work in the office.

Then, in 1917, Thomson died in Algonquin Park under mysterious circumstances and Harris, MacDonald and A.Y. Jackson took up the responsibility of publicizing and placing his work. In 1918, they achieved a real success - The Jack Pine was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

Then, when the Group of Seven was founded in 1920, Thomson was spoken of. “He should have been a member,” all agreed. Of course, Johnston, being a member, would have thought so too.

Johnston might not have thought about Thomson when he went to Winnipeg in 1921 but when he returned in 1924 and saw how Thomson and his work was beginning to become a legend, he must have thought about him a great deal.

At some time in these years, he essayed his observations of Thomson’s work in a magnificent tribute to the artist, Tribute to Tom Thomson.

If we compare Tribute to Tom Thomson with Thomson’s masterpiece The Jack Pine, we can see there is much that is similar. It is one artist's rendition of what there was about The Jack Pine that he admired. He chose to select the time of day as late afternoon or the approach of evening. Looking at The Jack Pine, we realize that is the time of day Thomson intended but with the addition of the colours of a northern sunset.

Johnston clearly worked from a sketch or memories of the northern landscape in the late summer or fall; Thomson from the first indications of winter. Johnston has yellow trees which seem to pop out of the hillside in the distance; Thomson had snow.

What may have kindled Johnston’s memories of Thomson’s great picture is the foliage of the trees with their drooping, trailing branches. They recall, however distantly, The Jack Pine. Or it might have been the shape of the trees - two trees at right, a smaller tree or tree form at left.

Whatever the trigger may have been, what we have here is a unique painting expressing one artist`s homage to another. There is great spirit in the depiction, nothing slavish. Johnston was his own man.

Besides, having worked in commercial art for years, he knew how to create strong design. He also knew how to depict glistening light.

He does so here. The silhouette of the trees against the sky is memorable; the foreground has a decorative, mosaic-like effect, which may reflect the kind of handling which Johnston learned through his work in tempera paint.

All in all, it is a magnificent realization, a summation of the northern landscape in the hands of a truly sophisticated artist.

Did he show the painting publicly? It must have been in one of the myriad exhibitions in which artists showed – and then sold - their work, perhaps in the Ontario Society of Artists shows where Johnston usually exhibited.

He may have felt it was too private a work to exhibit. It embodied his reverence for Thomson in a way that he may have wished to keep to himself. He may also have considered the painting to be too different from the main body of his work with its robust feeling for nature. On the other hand, perhaps he showed it under another title.

We have one clue. Johnston signed the painting “Frank H. Johnston,” a signature he used in 1924, but in 1925 changed to the more exciting way of styling himself “Franz Johnston.”

The painting seems to be dated stylistically to the period 1923-1925.

There is one review by a noted critic of the day, Hector Charlesworth, in which he complains of Johnston’s use of purple. He wrote in Toronto Saturday Night of the OSA show in March 1924, “An important group of canvases is shown by Frank Johnston (Winnipeg) in one of which his predilection for purple results in exaggeration. His best work is “A Night in September” painted in low tones and convincing in atmospheric treatment” (Hector Charlesworth. “O.S.A. Annual Exhibition. Technical Average High and Group System Disappearing.” Toronto Saturday Night, March 29, 1924. p. 3.)

Could our canvas be one of these works?

At any rate, the person who introduced it to the market, clearly felt that he (and perhaps this may have been the artist himself) or she couldn’t remember the title but did have an idea of the date and exhibition.

We have retitled the painting closer to Frank H. Johnston’s intention when he painted the work. It is a tribute, in our view, to both men, painting giants in a not so long-ago world.

Joan Murray

Previous|Next1of 1