Alert Bay, 1909: A Missing Link in Emily Carr's Work

This intimate and intense watercolour offers a missing link for our understanding of how Emily Carr developed her imagery of First Nations culture. In 1993, when I compiled my catalogue of all her paintings and drawings of First Nations villages, I listed the sketch of this subject as ‘lost.’ I am delighted now to see the original watercolour that Carr made in 1909, which became the source for her large oil painting of 1912 (now in the Beaverbrook Art Gallery).

During her first stays in Alert Bay (known as ’Y¬alis in the Kwakwala language) in 1908 and 1909, Carr made numerous small sketches there. However, Indian Village, Alert Bay is one of only four large-scale watercolours (all on heavy 37 x 55 cm paper) that show groups of the traditional multi-family houses and totem poles on the sea front. She considered this particular image so important that she made a major oil painting in her studio from it in her new French Post-impressionist painting technique even before she set out for her epic sketching trip to northern Native villages in 1912. That oil painting was later chosen as the cover image for her book Klee Wyck and for her National Gallery memorial show in 1945 because it crystallized so well her engagement with the Native peoples of the Northwest Coast.

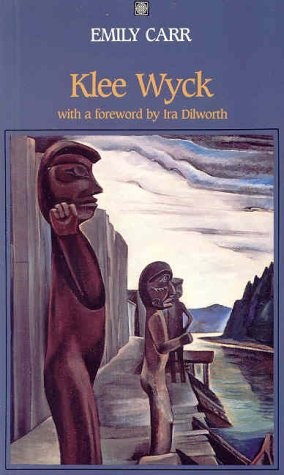

The cover of the first edition of "Klee Wyck" by Emily Carr (1941), featuring the 1912 oil on canvas derived from "Indian Village Alert Bay", 1909.

In Indian Village, Alert Bay Carr shows her fascination with the flourishing culture of the Kwakwaka’wakw people at the beginning of the last century. In the left foreground of the watercolour we see two huge carved posts of the kind that were designed to carry the interior roof beams of the big houses beside them. These posts, like the totem poles in the distance to the right side of the picture, carried the family crests of their owners – in this case two great thunderbirds perched on the heads of grizzly bears that hold human heads between their paws. The human heads would have symbolized ancestral chiefs whose mythical protector was the grizzly bear. On the bears’ chests are coppers, metal shields that were handed down and traded as tokens of a chief’s wealth. The adjacent big house has a gable also decorated with carved crests, an eagle at each end and a huge image of “Raven of the Sea” in the centre. In front of the houses stands an ancient war canoe, no longer used as such, but as a symbol of family wealth and status. We see that Carr appreciated the details and decorative features of Kwakwaka’wakw carving and the grandeur of the big houses, which she described in her 1913 Lecture on Totems as “dignified paganish mansions.”

Indian Village, Alert Bay is one of only four large-scale watercolours (all on heavy 37 x 55 cm paper) that show groups of the traditional multi-family houses and totem poles on the sea front.

This watercolour also shows how she balanced her interest in what she regarded as “Indian antiquities” with a very human response to the contemporary lives of Native people. In front of the big houses we see washing lines with clothes hanging out to dry – an affirmation of good housekeeping in this Native community – while a little group of women sits in conversation. Carr renders here a blend of the familiar with the exotic, as these women squat on the ground while another walking by has the flattened head that marks aristocratic rank. We know that she painted close-up studies of children in the village, and at least one portrait of an older woman.

Since the older Native people spoke no English, Carr would have had to communicate using a smattering of the Chinook jargon that was current on the coast. Settlers had little sympathy for Native cultures and Carr’s attempts to gain some understanding of the people involved reading books by missionaries and ethnographers who were often very biased. Yet Carr herself had a keen eye for the varied signs of changing Native lifestyles, and shows the village of Alert Bay as a bustling and prosperous place where native traditions were still practised. Indian Village, Alert Bay is thus a testimony to Carr’s artistic and human engagement with the Aboriginal population. Her decision to paint these Native villages and totem poles was made just when Native traditional culture was being forced underground and appeared to be vanishing. In the 1880s the government in Ottawa had banned the potlatch, a system of distributing wealth and conferring title that was central to the life of Native tribal groups. When Carr made this watercolour, ’Y¬alis was a dynamic centre for the Kwakwaka’wakw tribes living on the scattered islands and inlets of the Queen Charlotte Strait. Families from these Native villages had built houses on Cormorant Island in order to partake in the new economy being established by white settlers in the area. A postcard of Alert Bay made around 1910 shows the full row of eleven Native family big houses there, as well as the cannery and sawmill and the mission school established by white incomers. The postcard would have been made for purchase by tourists on cruise ships or travellers on the Union Steamship Line which made weekly stops there on its service up the east coast of Vancouver Island. Like the government’s Indian Agents, the settlers and tourists generally regarded the Native houses as barbarous and unsanitary dwellings, and the totem poles as grotesque curiosities. Carr herself sought to counteract such negative views and to record what she saw as the great achievements of Native traditional culture with watercolours such as Indian Village, Alert Bay.

At the time when she painted Indian Village, Alert Bay, Carr herself stayed in a hut just above the village, probably one built for seasonal workers at the fish cannery. She provides a vivid glimpse of her own lifestyle as a visitor there, describing an incident where she (“a white girl sketching about the village”) bought a baby racoon. It was imprisoned in a cage “in a narrow, draughty passage way between two Indian houses” and Carr bargained for its purchase and finally set it free (see the story “Balance” in Carr’s book Heart of Peacock). She returned to Alert Bay in 1912, with her mission to celebrate Native culture strongly reinforced by her contact with the cult of Primitivism in Parisian art circles. She once again painted the great thunderbird posts and the adjacent big house in a watercolour now in the National Gallery, showing that since her previous visit a new totem pole had been erected in front with the “Raven of the Sea” mounted at the top of it. Her imagery now gave more emphasis to the Native carvings themselves, and ultimately her stylistic concerns would lead her to eliminate human figures entirely. In the watercolour Indian Village, Alert Bay we have a precious example of Carr’s first encounters with the Northwest Coast Native population and her response to their cultural achievements.

Copyright © Gerta Moray, 2009