John Young Johnstone (1887-1930), Misplaced Painter Among Early Moderns

The secrets of the life of John Young Johnstone may never be known. Possessed with a dichotomous angst to be at once famous and yet unknown, he lived in estranged oblivion from society and died unwept. There are no substantive records chronicling his life anywhere. We must therefore depend on the evidence of his art for whatever estimates we make of him.

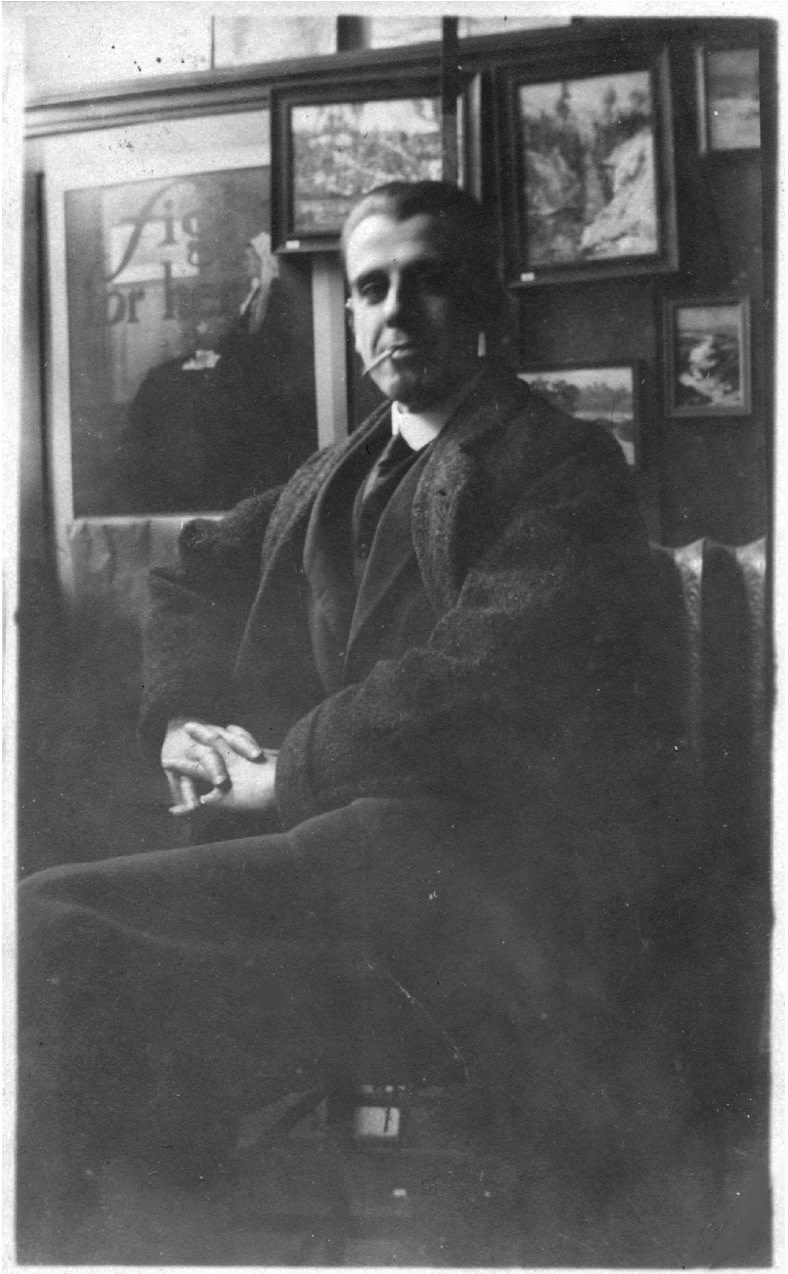

John Young Johnstone (1887-1930) in his studio

Born on November 12th, 1887, in Montreal, John Young Johnstone took his early art instruction from William Brymner (Canadian, 1855-1925) at the Art Association of Montreal and later studied with Lucien Simon (French, 1861-1945) and Emile-René Ménard (French, 1862-1930) at l’Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Despite his associations with such celebrated Canadian artists of his time as Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (Canadian, 1869-1937) and Alfred Laliberté (Canadian, 1878-1953), Johnstone remained a reclusive personality, as if suffering from a kind of ennui, which he endured by submitting to heavy drinking. Hardly a puritan, he was a handsome man who enjoyed a good living and while he remained a bachelor all his life, he suffered several failed romances, including one with a young woman named Cécile Bérard who later married the well-known art dealer William Watson (Canadian, 1887-1973). Art and alcohol were his compulsive passions.

John Young Johnstone’s paintings received attention as early as 1911 when his work was first exhibited at the Art Association of Montreal. Indeed, the Association exhibited his work intermittently until 1925, as did the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts to which he was admitted as an associate member in 1920, exhibiting from 1915 to 1923. He was a member of the Pen and Pencil Club and the short-lived Beaver Hall Group, and although teaching was not really a compatible occupation for the solitary painter, he found it financially necessary to teach at the Council of Arts and Manufacturers in Montreal.

Whilst he seldom dated his paintings, Johnstone’s work may be categorized into two periods. With some overlapping in style, the paintings from the earlier period, 1911 to 1915, are more structured than the ones that followed in the later period approximating from 1916 to 1930. The earlier work, although colourful, shows a delicacy of perception indicating that like most foreigners of his generation who trained in Paris, Johnstone studied not only the original Impressionists, but also the followers. For instance, the work of Suzor-Coté was surely influential in his treatment of perspective. Like Suzor-Coté, he recurrently employed the syntax of the “S” curve, providing a diagonal spatial thrust in his compositions. Also, like Maurice Cullen (Canadian, 1866-1934), he invested his subjects with a preternatural stillness, restraining any descriptive vein in his painting in favour of a stoic presence. However, he remained during these years still an artist in evolution, painting with the immediacy of his passions while reflecting influences from a variety of sources.

John Young Johnstone’s painting reached a subtle but sure maturity from about 1916 onward, setting the tone for the later period of his work. His choice of subject matter, no doubt, continued a relation to the Impressionists he admired, but he had added another dimension to his own perception of it. Instinctively, he was now rendering not a fleeting moment like the Impressionists, but an immeasurable duration that emphasizes the suspension of time. Like his elder contemporary James Wilson Morrice (Canadian, 1865-1924), who depicted sights along the streets and boulevards of Paris or Venice with a child-like joy, Johnstone painted in France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, and mostly Quebec, exploring the mysterious possibilities in gradation of colour hues in order to evoke the most essential perfume of activities under his observation. The “toning down” of colours from the earlier years to a whispered chorus of low notes found in the later work creates a certain mystery in his painting. A mystery that is synonymous with the mystery of his own life.

Johnstone’s fusion of images in his painting is by no means as complex as Morrice’s. Nor is there, in his little panels, the depth of melancholy of the elder painter. But there is, in such panels, a fugitive note of anonymity, a subtle gloom that is truly his peculiar gift. And the very compactness of these pictures, suggestive as they are of the imagery inherent within them, recalls Morrice’s swiftly painted pochades. Whilst Johnstone’s practice of painting little panels like Morrice inevitably leads to invidious comparisons of their respective styles, there is no evidence that he ever wished to emulate Morrice. In Johnstone’s painting there is a constant reminder of his own being: A man who was destined to walk a lonely path, who felt it necessary to keep a certain distance from the world. A man who displayed respect for tradition yet was one of the first of the Moderns among all the Canadian painters at the dawn of the twentieth century.

It is a paradox that John Young Johnstone, who so brilliantly painted small panels with consistency, was unable to achieve the same distillation of subject matter in his larger canvases. The intimacy and a restricted view offered in his panels are somehow missing in his larger canvases. Despite his gifts as a painter, it seems that as he drifted through life, pouring out the immediacy of his soul with a razor-edged passion evident in his small panels, his skill for compression was lost in the larger works. Clearly, as his small works created in tandem with his environment convey his secret longings, the larger ones done in sobriety, portray the outside world getting in his way. He seemed a reactive man, in complete control of painting when working en plein air, but unable to become a reflective man, as required when working contemplatively on larger works in the studio where painting seemingly took control of him.

John Young Johnstone’s defeat from life, such as it was, is perhaps traceable to his vulnerability as a fragile, if not emotionally distraught individual at the dawn of the twentieth century, afraid of a new age for mankind. His paintings bear witness to his struggles to retain something of his original feelings. They are examples of one man’s expression of longing for a world long past and his desire to remain sheltered within it. The economic hardships faced by an artist encountering the challenges of a new century must have frightened him. And he must have suffered with deeper discomfort leading to a progressively unbearable need for alcohol. The choice, however, was his own and he obviously succumbed to a losing battle with psychological forces that were apparently beyond his control. The extraordinary quality of his intimate sketches, however, can never be denied.

John Young Johnstone’s private world of images continues to be somewhat unique in Canadian art. Admired by discerning critics and collectors from the moment his art was first exhibited, Johnstone’s work has retained its artistic integrity in spite of the neglect it has suffered from the art establishment. This could partly be due to his tendency to drift and live a nomadic existence, contributing to a short life that ended on February 13th, 1930, in Havana, Cuba, where he had gone only six weeks earlier. Death condemned him to live no longer except through his art, the only medium that helps us today to reconstruct the life of a gifted artist that history has misplaced.

The author is grateful to Charles C. Hill, curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, for his review of this essay.

© Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc.