Reminiscences of Robert Pilot

How I first came to meet Robert Pilot I can now no longer recall. At first, certainly, we had little enough opportunity to encounter one another. While he was serving as a camouflage officer in the Italian campaign of the Second World War, I had been working as an engineer for the Department of Marine Construction in Montreal. As Pilot prepared to come home at the end of hostilities, I undertook to visit Europe, only returning in the first weeks of 1949. While still employed in my original profession I came to realize that an art gallery would be much more congenial to my temperament and inclinations.

In those exciting early years, I may first have met Robert Pilot through his fellow members of the Royal Canadian Academy, from whom I soon began to acquire paintings. Indeed, it is also just possible that the artist may have known of me and of my ambitions through a friend whose brother was married to Mrs. Pilot's twin sister. Be that as it may, Pilot soon showed me considerable kindness and encouragement. This was evidenced, not so much in work as in deed, in the opportunity Pilot afforded me to buy a great many of his best pictures. The older and established dealer, William Watson, and to a lesser extent, Joseph Schima, of the Continental Galleries, had dealt with Pilot for many years. They may well have envied me these acquisitions and wondered at my success. It is of course true that I was always happy to buy these paintings outright whereas my colleagues were accustomed to obtaining their work on consignment, in other words, on a sale or return basis. Mr. Watson, the pre-eminent art dealer of his day in Montreal, championed above all Pilot's stepfather, Maurice Cullen, and referred to and addressed Pilot as "Bobby." I imagine that this may have rankled Pilot at a time when he had become one of the most distinguished of Canadian painters and, indeed, President of the Royal Canadian Academy, 1953-54.

I remember that on a visit one day to Pilot's studio on Peel Street, I saw a lovely painting. The scene was of a subject not far from the studio, looking up Peel from the south side of Sherbrooke Street on a wintery evening. It was a characteristically poetic composition. At that time, a large advertising sign was suspended in front of a building on the south-east corner and Pilot had included it in the pictures. He had, however, often told me and indeed demonstrated how he would quite automatically eliminate certain features of a composition, sometimes transposing trees or houses, and all in the interests of a better composition. I was therefore curious as to why he had perhaps not thought to remove the sign. As I was anxious to buy the picture, I asked the question. I fully expected to hear as answer "well, if you don't like the picture don't buy it!" Pilot did not practice salesmanship any more than he compromised in his art, but as he reconsidered his canvas, he complimented me by saying that he thought I had something and asked me to call the following day. On my return, I loved the painting at once. Mr. Bartlett Morgan, who lived just up Peel Street, bought the picture and some years later it was exhibited in the Retrospective Exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts. The colour reproduction of the work appears on page thirty-seven of the show's now rare catalogue. This painting may also be seen in our own current exhibition.

I sometimes wonder if Pilot ever regretted not having joined the Group of Seven. He certainly could have done so, as could Randolph Hewton and Albert Robinson. In 1920, the three were invited to exhibit in the first Group of Seven Exhibition in Toronto. On that occasion they did exhibit with the Group but declined to formalize their union. Had the course of art history been otherwise today we might have been lionising a "Group of Ten." However, Robinson later confided in me that the three simply could not share the philosophy of the others. They did not feel compelled to paint the remote wilderness of Canada, but preferred those inhabited places, particularly the Lower St. Lawrence region. Another factor must undoubtedly have been that Pilot and his two confreres were based in Montreal and maintained close ties with the artists who became the Beaver Hall Hill Group of painters. The Group of Seven had its base in Toronto, where Lawren Harris had built the Studio Building expressly for them. A.Y. Jackson, a life-long friend of Pilot, helped to reconcile the two groups and their philosophies. In the spring, in his native Quebec, Jackson painted with his friends along the banks and rolling country of the St. Lawrence; during the remainder of the year, he ventured to the wilderness reaches of the North and the West. Pilot's first love as subject was always Quebec.

Among painters, Pilot felt the greatest admiration for Camille Pissarro, while his favourite Canadian artists were Albert Robinson and James Morrice. Pilot's stepfather and mentor, Maurice Cullen, was also particularly revered. Cullen's art was ahead of its time in Canada. Willie Watson used to tell me that he lost money on every Cullen he ever sold. He charged a commission of fifteen percent and his overhead expenses in operating the first business establishment on Sherbrooke Street had been twenty percent - but he considered it a privilege to represent Cullen and his work. In common with so many of the great painters, Cullen, like his stepson after him, was very modest about his achievements. Of course in the long run quality is all that matters, yet unfortunately people are often inclined to accept at face value the bombast that advertises rather than the reticence that conceals a quiet virtue. It may have been possible for Churchill to quip of Clement Attlee, "he is a modest man - and has much to be modest about," but not so Robert Pilot, whose accomplishments are considerable, although until recently sometimes neglected.

During the time, Russell Harper was working on his history, Painting in Canada, he elicited Pilot's help for his research on Cullen. Pilot, courteous and attentive as always, invited Harper to lunch at his club, the Saint James's. This I fear was a mistake, as I could have warned the artist. Harper was a good historian but he was in some ways a frustrated and bitter man. He deplored his own straitened circumstances and was a sycophant of the very rich whom he helped in their art collecting. Harper was occasionally asked to their dinner tables as compensation for the remuneration for which he was too timid to ask. I suspect that deep down he resented successful people, particularly successful artists. Harper must have realized that while he had sought Pilot's help, Pilot had not required Harper's to further his career. The historian asked no questions regarding Pilot's own work and ignored his pictures while visiting his home afterwards. Harper made no reference to Pilot either in the text or index of, Painting in Canada. This omission reflects on the art historian and not on the artist.

Pilot often helped me in ascribing titles to pictures as well as authenticating and dating both his own earlier works and those of Cullen. Having been a friend of Clarence Gagnon, Pilot had an excellent knowledge of this accomplished painter's art, and, as I soon discovered, knew his Quebec well. When the Harper book was first published, Madame Gagnon telephoned me in some consternation and drew my attention to a painting reproduced and attributed to her husband. It was identified as a "View from Lévis" and I had already recognized it as questionable. Madame Gagnon had not been consulted and had not consented to the reproduction. She suspected the work to be a forgery but asked Pilot for his opinion on so delicate a matter. Pilot considered the painting and declared without hesitation that not only could it not be a Gagnon, but it could certainly not be a view from Lévis. However, since the book had been published and Pilot could not imagine that Gagnon's reputation could suffer, Madame Gagnon discreetly dropped the issue. The reproduction did not appear in the second edition of Harper's history.

Pilot, like many artists, required and appreciated the stimulus and encouragement derived from seeing that people enjoyed and bought his work. It must be so much more difficult to stave off discouragement if work is simply left to pile up. Pilot never allowed this to happen and indeed such a problem never presented itself.

Robert Pilot died in December of 1967. It has now been twenty years since his memory was paid tribute in the Retrospective Exhibition which opened in Montreal in the fall of 1968. This year (1988) also marks the ninetieth anniversary of his birth, and we deem it time to assemble this exhibition in commemoration and honour of his considerable talent and contribution to art in Canada.

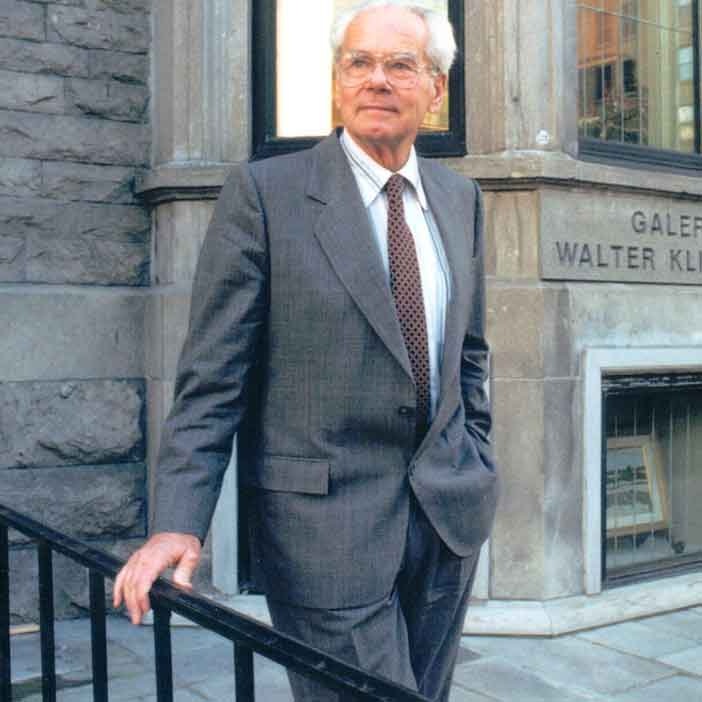

I write these few personal reminiscences by way of introduction to this exhibition in our gallery. With regard to Pilot's work, I shall let it speak for itself. In conclusion, I will only remark that in our home over the mantelpiece we have a Pilot.