Fine Art and Floor Tiles

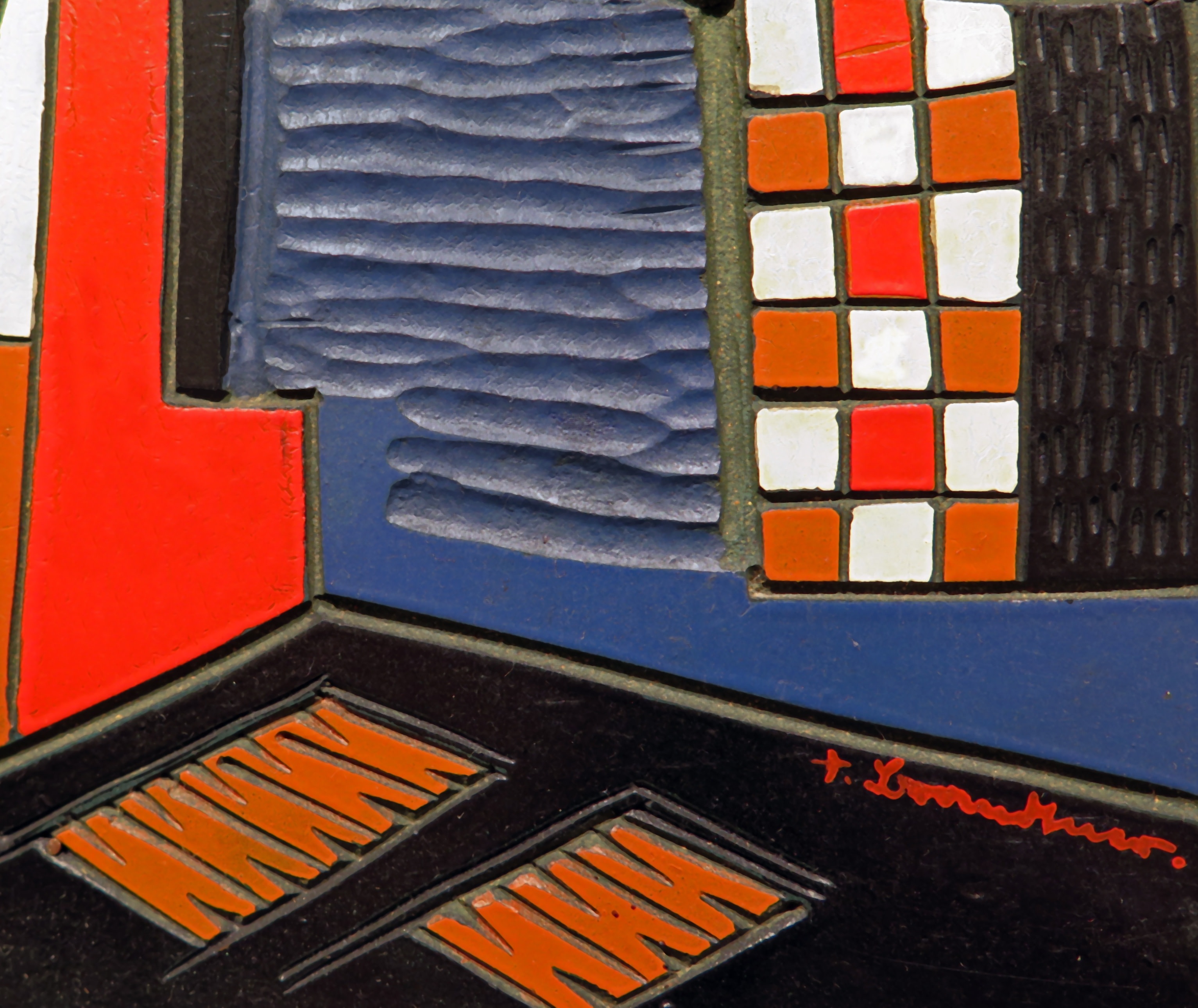

Fig. 1

Friedrich Wilhelm (Fritz) Brandtner (1896-1969)

Factory Worker (Machine Shop), c. 1938/9

Oil on linoleum panel, 12 x 12 in (30.5 x 30.5 cm)

signed "F. Brandtner." (recto, lower centre).

Provenance

Private collection, Montreal;

Walter Klinkhoff Gallery, Montreal;

Private collection, Toronto.

Previously sold by Alan Klinkhoff Gallery.

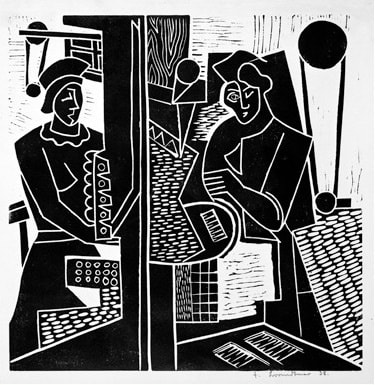

The present linoleum panel, Factory Worker (Machine Shop), c. 1938/9 [Fig. 1], was used to produce one of Brandtner's linocut prints on paper. The Glenbow Museum houses an impression of the print, which it has titled and dated Machine Shop, 1938 [Fig. 2] [1]. In The Brave New World of Fritz Brandtner the print is referred to as Factory Worker, a title cited in Observations on a Decade 1938-48: Canadian Print Making by Betty Maw [2].

Fig. 2

Fritz Brandtner, Machine Shop, 1938, linocut on paper, Glenbow Museum Collection

In her article, Maw praises Brandtner as one the more “interesting” artists working in the relief process medium and notes that in his works “one finds the few fine examples of a vigorous and experimental approach to technique and design” [3]. She uses the linocut print created from the present painted block to illustrate Brandtner’s adeptness in the medium [4].

Brandtner, however, advocated for linoleum carving as more than simply a means to a printed end. In his 1949 article, Linoleum Carving, Brandtner discusses the use of linoleum for creating works in low relief [5]. Brandtner writes, “The desire of a few creative artists to experiment with this material has let them find in carved linoleum a new and excellent medium for direct expression. As a result, low-relief carvings of great beauty in design and texture have been produced” [6].

Brandtner suggests linoleum as an alternative to wood carving, as the surface of linoleum responded more readily to the intention of the artist’s knife, gouge, and chisel [7]. Linoleum accommodated his abstract and Cubist tendencies as wood never could, its soft surface more readily permitting the angular swelling and tapering of line. The artist notes, “[...] slinoleum calls up ideas that lead us away from pure representational and towards the abstract. Therefore abstract qualities of design will give the greatest satisfaction, will bring an intense life of their own into linoleum carving” [8].

Brandtner continues,

Every material has its own unique qualities. Only when there is a clear relationship between material and design, technique and texture do we feel that the result we have achieved in our work is dynamic. The material has to have a chance to take part in shaping the idea. Linoleum is a synthetic material, it is man-made in contrast to wood which is an organic substance [9].

Linoleum — made primarily of linseed oil, rosin, and powdered cork with a burlap backing — was initially an inexpensive and common floor tile [10]. Brandtner welcomed industry and extolled the machine, often depicting “the industrial world and the integration of man into the machine…” [11]. Because of Brandtner’s affinity for the mathematical precision that modern engineering and industry provided, the very synthetic nature of linoleum made it uniquely and ideally suited to depict an image that celebrates the energy of the modern factory [12]. The rawness of the carved linoleum, with its lively chinks and divots, is a befitting support on which he could convey this industrial scene.

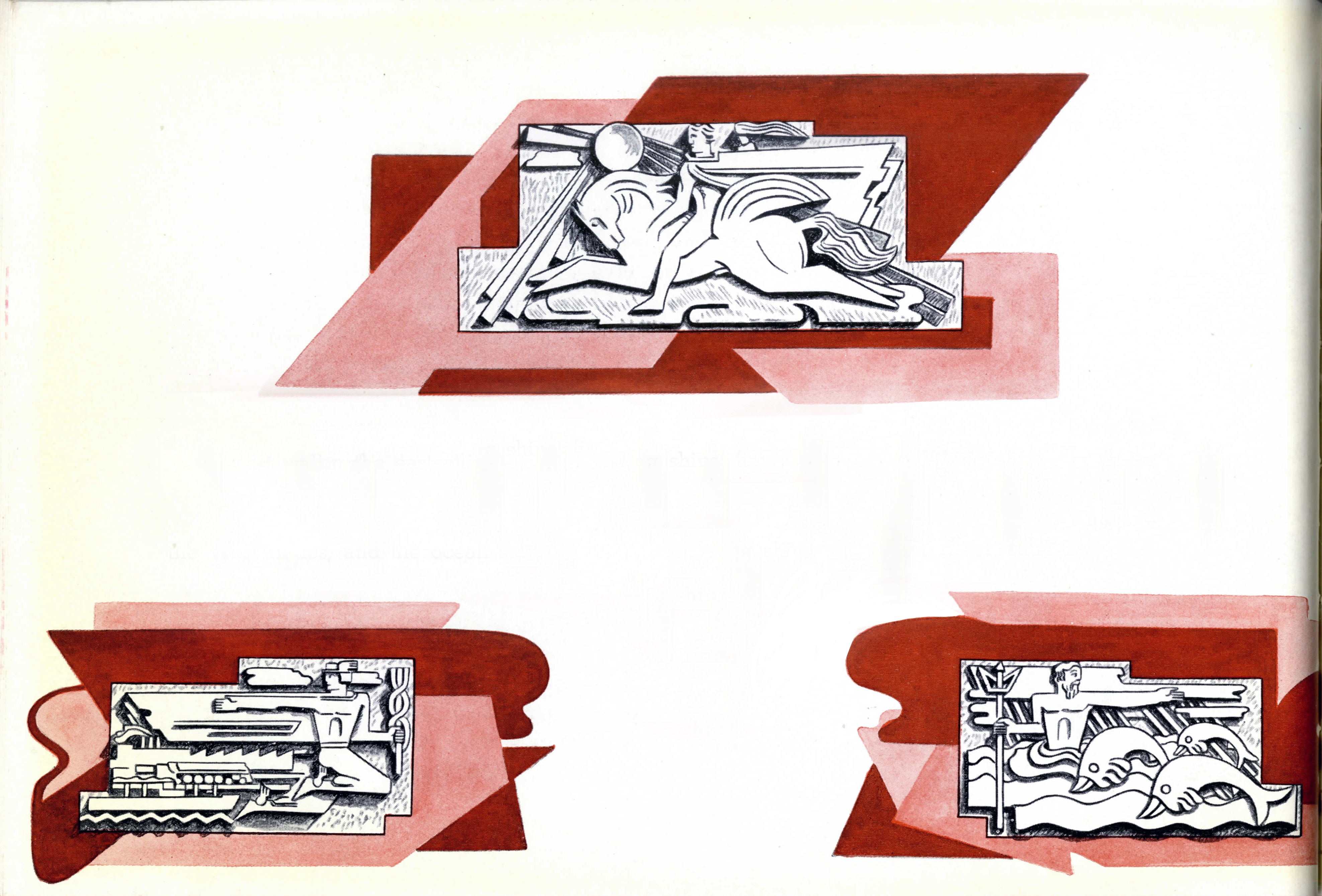

Fig. 3

Detail of Factory Worker (Machine Shop) showing the various cuts of Brandtner’s tools in the linoleum surface.

Flat areas of searing red hues dominate the work and are sharply contrasted by complementary greens and blues, likewise contained in carefully delineated facets. Brandtner crowds the two figures and their equipment, pressing everything to the fore of an ambiguous pictorial plane. Fractured spaces are intertwined in a tight mosaic, making the surface of the work appear to surge, while the essential linearity tempers the motion. The malleable surface of carved linoleum allowed for Brandtner to create an image with such energy that the composite machines become an indistinguishable extension of their operators. The geometric forms of the machines are repeated in the shapes that he employs to compose his figures, reinforcing the relationship of the workers with their tools.

The sturdy bodies of the working figures recalls the strapping bas-relief figures of the ancient gods that Brandtner depicted for the walls of Montreal’s Central Station [Fig. 4 & 5]. As with his stone deities, Brandtner’s depiction of the workers in the present linoleum panel “is in the modern idiom, more abstract than representational [and their] outlines are cut bold...” [13]. Brandtner’s Factory Worker (Machine Shop) is likewise an ostensibly traditional subject — figures in an interior scene — but is composed with a new artistic vocabulary that saw the liberation of line and colour from a representation role to one of expression. The workers, like the mythical figures of the Montreal terminal, are marked by a superb balance of design, a hallmark in the relief works of Brandtner.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4 The three large bas-reliefs, which depict Mercury, Prometheus, and Neptune on the north exterior wall, were obscured by the late 1950s construction of the neighbouring Queen Elizabeth Hotel. [14]

|

Fig. 5 Postcard of Central Station before the creation of the Queen Elizabeth Hotel.

|

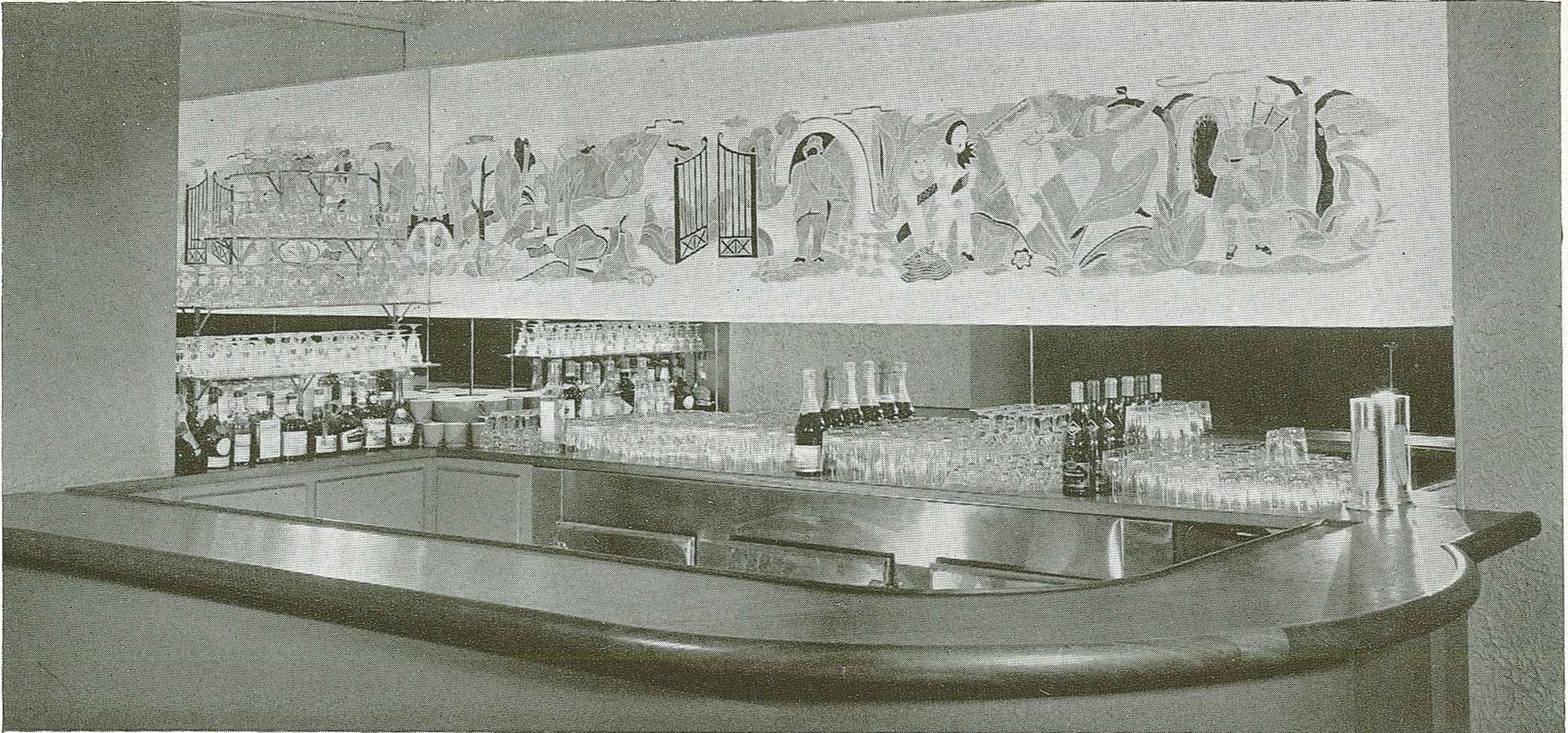

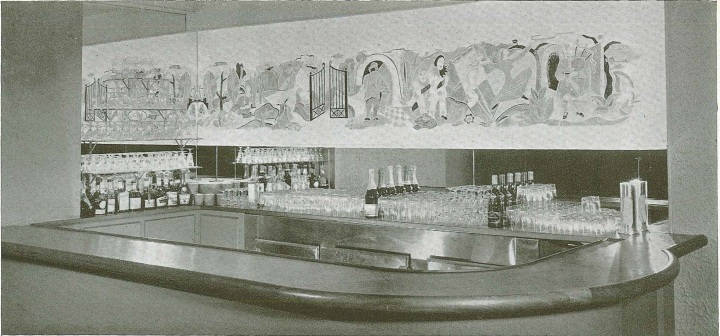

Around the same time as Factory Worker (Machine Shop), Brandtner was tasked with creating linoleum murals for the Berkeley Hotel in Montreal [Fig. 6]. The carved and coloured linoleum surfaces decorated the cocktail bar in “a gay, stylized pattern of trees, flowers, and figures in clean bright blues, reds, greens, and yellow” [15]. Brandtner would continue to create linoleum carved murals for various locations across Canada, including for the Canadian National Railway Company’s Vancouver ticket office and a 12-foot-long relief for the ballroom of the Newfoundland Hotel in St. John’s [16].

Fig. 6

Brandtner’s mural above a bar in the Berkeley Hotel (now part of the Maison Alcan building structure).

Brandtner’s interest in workers on the industrial front would continue after his execution of Factory Worker (Machine Shop). In 1943 the National Gallery held an exhibition of drawings by Brandtner and fellow artist Louis Muhlstock, which were sketched at Canadian Vickers Limited, an aircraft and shipbuilding plant that received numerous contracts following the outbreak of WWII [17]. For his semi-abstract drawings in this show, critic Walter Abell praised that they, like the present panel, illustrated “something of the feverish intensity of our age...” [18].

Art critic Robert Ayre wrote, “Vitality goes through everything Fritz Brandtner does [...] [He is a] lover of the visible world, especially that part of it that has been made by man — the city, with its buildings, lights, machines, docks, boats, its traffic, its tensions and its clamor […]” [19]. The machinists in the present panel appear substantial and admirable because, for Brandtner, they represent something substantial and admirable. In its industrial subject, in the animation and textual variety for which the surface of the linoleum panel allowed, and in the brilliance of Brandtner’s colours as well as the rhythm of his lines, Factory Worker (Machine Shop) is a trumpet call that honours the surge of modern society.

Alan Klinkhoff Gallery would like to extend thanks to Mr. Soren Schoff, LSA - Public Services, Kohler Art Library University of Wisconsin - Madison and Ms. Heather Home, Public Services and Private Records Archivist, Queen’s University Archives.

ENDNOTES

1. In the exhibition catalogue for the Glenbow Museum’s show Images of the land : Canadian block prints, 1919-1945 (Patricia Ainslie, 1984), the print is entitled, Factory Worker with Machine Shop as an alternate title. See cat. no. 25., pp. 77, 78, & 120

2. Helen Duffy & Frances K. Smith, The Brave New World of Fritz Brandtner, (Kingston, Ont.: Agnes Ethething Art Centre, Queen’s University, 1982), cat. no. 35, reproduced p. 70 as “Factory Worker, linoleum cut print on paper, 30.5 x 30. 5 [cm], inscr. l.r. F. Brandtner 39”

3. Betty Maw, “Observations on a Decade 1938-48: Canadian Print Making”, Royal Canadian Architectural Institute of Canada Journal, vol. 25, no. 3, January 1948, p. 24

4. Ibid., pp. 25 & 30, fig. 30.1, reproduced p. 24, as “Factory Worker, Lino cut, Fritz Brandtner,

Courtesy of the Artist”

5. Fritz Brandtner, “Linoleum Carving,” Canadian Art, Vol. 6, no. 4 (Summer 1949), p. 164

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., pp. 164, 166

8. Ibid., p. 166

9. Ibid.

10. Corky Binggeli & Patricia Greichen, Interior Graphic Standards, 2nd ed., (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), p. 377

11. Denis Martin, Printmaking in Québec, 1900-1950, (Quebec: Musée du Québec, 1990), p. 56

12. Robert Ayre, “Fritz Brandtner : The Artist as Engineer”, The Montrealer, October 1957

13. Canadian National Railways, New Montreal Terminal, [s.l. (Montreal?): s.n., 1943], unpaginated

14. Incidentally, Brandtner would later be commissioned to create a group of linoleum carvings to decorate the Queen Elizabeth Hotel.

15. Charles Geoffrey Holme, ed., Decorative Art: The Studio Yearbook, 1942, (London: The Studio, 1942) p. 78

16. Duffy / Smith, 1982, p. 91

17. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ont., Exhibition of work done in Canadian war plants by Fritz Brandtner and Louis Muhlstock, 17 July - 15 August 1943

18. Walter Abell, “War Industry Drawings by Muhlstock and Brandtner”, Canadian Art, vol. 11, no. 1, Oct/Nov. 1943, p. 20

19. Ayre, October 1957

EXTERNAL IMAGES CITED

Fig. 2

Fritz Brandtner, Machine Shop, 1938, linocut on paper, Glenbow Museum Collection, Calgary, Alberta, Gift of Shirley and Peter Savage, 1995, Accession No. 995.018.090

Fig. 4

Canadian National Railways, New Montreal Terminal, [s.l. (Montreal?): s.n., 1943], unpaginated

Fig. 5

Canadian National Railways Central Station, Montreal, P.Q., Canada - 99, (Ottawa: Photogelatine Engraving Co. Limited, [194-?]), Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, No. CP 031327

Fig. 6

Charles Geoffrey Holme, ed., Decorative Art: The Studio Yearbook, 1942, p. 78, courtesy of Soren Schoff, LSA - Public Services, Kohler Art Library, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA

![Fig. 4 The three large bas-reliefs, which depict Mercury, Prometheus, and Neptune on the north exterior wall, were obscured by the late 1950s construction of the neighbouring Queen Elizabeth Hotel. [14]](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_720,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy/ws-klinkhoff/usr/blog_entries/images/8210/brandtner-railway-illustrations.jpg)

![Postcard of Central Station. Canadian National Railways Central Station, Montreal, P.Q., Canada - 99, Ottawa: Photogelatine Engraving Co. Limited, [194-?], Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, No. CP 031327](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy/ws-klinkhoff/usr/library/main/images/cn-montreal-banq.png)