Klinkhoff Honours Overlooked Painter: Sarah Robertson

Montrealer Robertson deserved a better fate

ANN DUNCAN - Gazette Art Critic THE GAZETTE Saturday, September 12, 1991

Montreal painter Sarah Robertson has all but fallen through the cracks of history. After all, it has been 40 years since she was accorder her only solo exhibition. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada, it took place three years after she dies at the age of 57. But the current Robertson retrospective at the Galerie Walter Klinkhoff proves that she deserves a better fate than as just a footnote in some obscure art book. Robertson took risks, often had a deft touch with colours and had her own particular vision, no matter what the subject. While her work varies in quality, it is easy to see from this exhibition of 56 oils and watercolours the strength of Robertson's commitment to her art and to stretching her limits.

Referring to Group of Seven colleagues Lawren Harris and Edwin Holgate, A.Y. Jackson told Robertson, "You are a finer colourist than either of them." "She has the courage to create landscapes, and not copy them literally," Arthur Lismer, the renowned art teacher and Group of Seven member, wrote about her. What is particularly remarkable about Robertson is that she managed to make great strides in her work despite an extremely low lifetime output, said Eric Klinkhoff, a director of the family-run gallery.

Nothing is for sale

She managed to paint only two or three canvases a year because of poverty, ill-Heath and a demanding invalid mother who absorbed much of her time. Robertson was so hard up that Jackson used to buy her work so that she could afford to go to Toronto to see exhibitions that included her paintings. And one of the paintings in the Klinkhoff show - the gallery's annual public-service exhibition in which nothing is for sale - was purchased by Jackson and then given to Art Gallery of Ontario.

"The quality of the work is amazing given that she had so little time to paint and given that she has so little encouragement," Klinkhoff said. As with most women artists during the 1920s and the 1930s, Robertson was often dismissed as a dilettante, a Sunday painter who was merely dabbling in art, said Barbara Meadowcroft, who wrote the exhibition catalogue. "This was not something they did in their spare time," Meadowcroft said of Robertson and her fellow female artists, such as Prudence Heward, Anne Savage, Ethel Seath and Kathleen Morris. "This was their purpose in life."

Lack of recognition

And the seriousness of that intent, as well as the obvious quality of the work, are what distinguish these women from amateur artists, Meadowcroft said. But what sustained these women during all the years of little public recognition, poor sales and their nagging self-doubts was their mutual friendship", Meadowcroft said. They were all members of, or associated with, the Beaver Hall Group, a short-lived organization of artists that was founded in the late '20s, and their friendship continued for most of their lives.

"They formed what we would today refer to as a network," Meadowcroft wrote in the exhibition catalogue. "They supported each other in times of trouble, shared news of the art world, and encouraged each other to exhibit . . . And I think this bond is one of the main reasons why they could stick at it (their art)." There is no doubt that these women were held back by sexism, Meadowcroft said. Art, in those days, was a man's world - the art was predominantly made by men, galleries were owned by men, museums were run by men and men obviously controlled the purse strings when it came to buying art. And all this was exacerbated by the domination of the Canadian art scene by the Group of Seven, Meadowcroft said. The Group had a pioneer approach to art-making with their frequent sketching trips into the wilderness, which were a sort of male-bonding sessions. "It was a very macho thing."

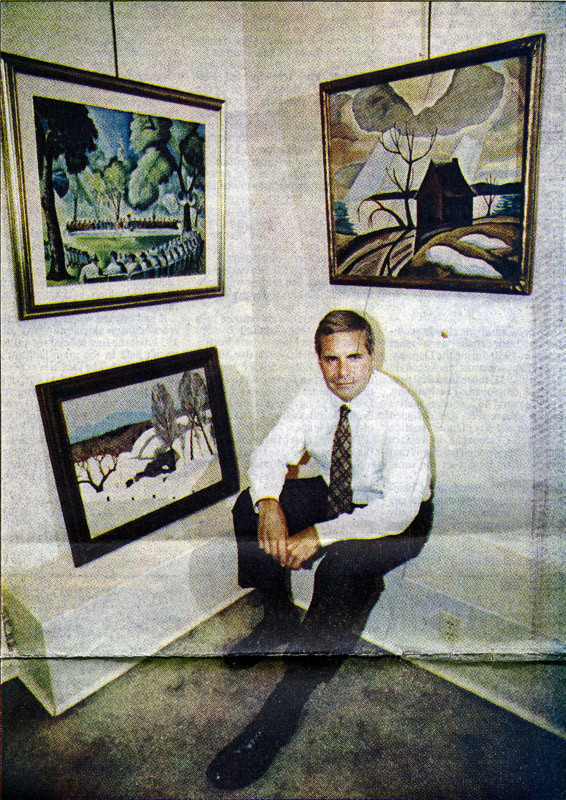

ROBERTSON Montreal artist finally emerges from obscurity

So the Beaver Hall women tended to produce landscapes rooted in their immediate environments - street scenes full of people or country landscapes as seen during weekend jaunts. Robertson, who lived on Fort St., was as likely to paint the Mother House - now Dawson College - around the corner or a convocation-day scene at nearby McGill University as she was to paint a rustic church in St. Matthias sur Richelieu where a friend had a home. (The slightly stopped and rumpled figure in the foreground of Robertson's convocation painting is probably Jackson, her long-time friend and supporter.) But for all the long neglect of Robertson and the other Beaver Hall women, there are signs that we are beginning to appreciate the historic role they played.

Meadowcroft, an adjunct fellow at Concordia University's Simone de Beauvoir Institute, is now writing a book about these women and their work is beginning to be exhibited more often. Robertson's painting Storm, Como, for instance, came to the Klinkhoff show after being included in London last summer in a survey exhibition of Canadian landscape painting. And that show, the first major exhibition of Canadian art in the British capital in decades, earned rave reviews from local critics. But a big chunk of the credit for a revival of interest in these women and their unique contribution to art in this country had to go to the Klinkhoff gallery.

For two decades now, the gallery has each fall put together museum-quality exhibitions of the work of the Beaver Hall Group purely as a public service. None of the paintings in these shows is for sale, and the gallery staff goes to great effort and expense to organize these exhibitions. The Robertson show will cost about $25,000; the paintings have come from across the country, including from the National Gallery of Canada, the McMichael collection in Ontario, the Robertson McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa, the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. And the out-of-pocket expenses do not include the cost of staff time to put the show together or the loss of potential sales while the gallery is filled with art that is not for sale. "This is a way of giving something back to the community that supports us," Klinkhoff said.

The Sarah Robertson retrospective continues at the Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, 1200 Sherbrooke St. W., through next Saturday. The gallery is open Mondays through Fridays, 9:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m. As with all commercial galleries in town, admission is free. Copyright © The Gazette

Add a comment