Anne Savage

"The part of the country which is my real locale is a little lake in the Laurentians... this beautiful little lake. A very deep, clear, cold water... And the country around this puddle was very undulating. It seemed to have little hills, and little ravines so that, without going for more than a very short distance, you could sit down, turn your back and you would have a complete new composition."

Anne Savage, 1967

"The part of the country which is my real locale is a little lake in the Laurentians... this beautiful little lake. A very deep, clear, cold water... And the country around this puddle was very undulating. It seemed to have little hills, and little ravines so that, without going for more than a very short distance, you could sit down, turn your back and you would have a complete new composition."

Anne Savage, 1967

by Dr. Barbara Meadowcroft

For over thirty years, Anne Savage was well known in Montreal as an art educator. Her achievement as a painter was less appreciated. Although she contributed to the big international exhibitions of the 1920s and 1930s and exhibited regularly with the Canadian Group of Painters, she was not accorded a retrospective show until 1969, when, to her great delight, her former pupils organized the Anne Savage Retrospective at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University).

Since Savage's death in 1971, appreciation of her painting has grown with the mounting of a circulating exhibition, Anne Savage: Her Expression of Beauty, organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Janet Braide's catalogue for that show and Anne McDougall's memoir of her aunt, Anne Savage: The Story of a Canadian Painter, have provided valuable insight into the artist's life and work.

Savage was born into an upper-middle-class family at the end of the Victorian era. In this social milieu, women were encouraged to practice their talents within the family circle; and yet as McDougall and Braide have shown, Savage had a professional career. What prompted Savage to become a professional artist? What role models did she have? And how did she manage to combine the two careers of artists and teacher?

Annie Douglas Savage and her twin brother Donaldson Lizars were born in Montreal on July 27, 1896. As an adult, the painter rejected the name "Annie" in favour of the more dignified "Anne." Her father, John George Savage (1840-1922), a Montreal businessman, was a widower with seven children when he met Helen Lizars Galt (1849-1942). They were married on April 6, 1893. John and Helen, or Lella, as she was called, had four children: Helen Galt (b. September 25, 1894), the twins, and Lilias Elizabeth, known as Queenie (b. July 12, 1898).

Sometime after Queenie's birth, the family moved to a farm in Dorval. Anne Savage believed that growing up in the country kindled her life-long love of nature. In an autobiographical sketch, she speaks of the sensuous delight she took in the apple blossoms, the piercing notes of the early robin, and the scarlet berries of the rowan trees. She added, "the beauty of growing things, from the bud to the scarlet leaf and finally the bare branches, all held a mystery for me."

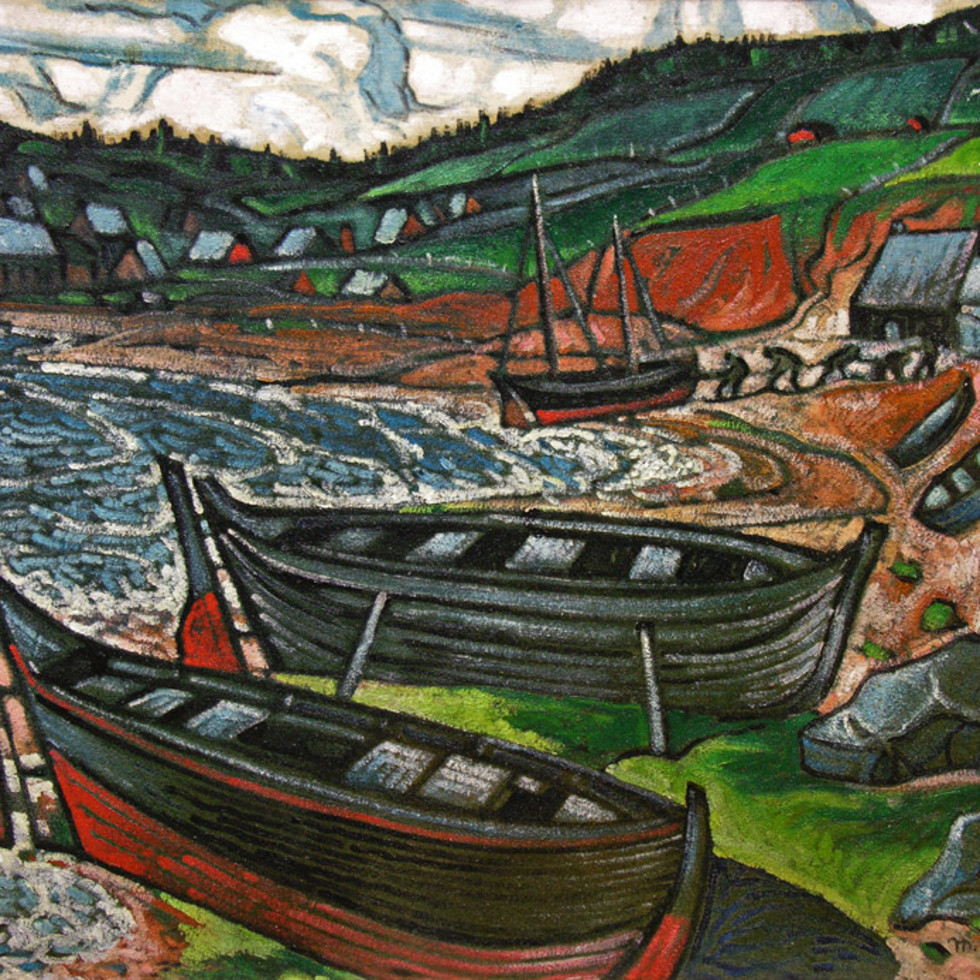

In the summers, Savage's family, including her half-brothers and sisters, all went down to Métis, on the lower St. Lawrence. Savage held the sea "in absolute awe," as she told Arthur Calvin, a graduate student. "It was so great and so powerful." Nevertheless, Métis, with its majestic rocks and sandy beaches strewn with shells and seaweed, stimulated her imagination. As an adult she returned frequently to paint, usually in early summer.

In 1911, John Savage bought a small lake in the Laurentians, about eight miles from Morin Heights. Lake Wonish became a sacred place for Anne Savage. It was both a place for fun with family and friends and a retreat where she could paint.

The first summer at Wonish, however, must have been a shock for the Savage family. The newly-built cottage had no electricity or running water. A forest fire had devastated one side of the lake, leaving hardly a green tree standing. But for the teenage children the most difficult thing to accept was the isolation. They were cut off from the pleasant social life of Métis and forced to invent their own pastimes.

In studying the lives of creative women, I have often noted an event (such as an illness or a move) which temporarily isolates the woman and forces her to explore her inner resources. For Anne Savage the summers at Wonish, when she was in her middle teens, may have provided just such an opportunity.

Savage was fortunate in having as role models two talented women, her mother, Lella, and her aunt, Minnie Galt Clark. Lella and Minnie were the granddaughters of John Galt, novelist and founder of Guelph, Ontario, and nieces of Sir Alexander Galt, one of the Fathers of Confederation. As such, they fostered in Anne a sense of family pride and an awareness of history. Lella, who had been a teacher before marrying in her middle thirties, passed on her love of reading to her daughter Anne.

Minnie Clark, an amateur painter, used to visit the Savage family in Dorval. Pointing out that Minnie "inherited" her talent from her own aunt, Savage stresses the importance of role models in the development of young children. As a child of six, Savage would watch Aunt Minnie painting the maples covered with snow outside the window. Savage credits Minnie Clark with awakening in her the desire to paint and with teaching her to look at everything with a view to "doing it."

Savage's experience at the Montreal High School for Girls, which she attended from 1904-14, confirmed her belief in her ability to paint. Although she kept up an average of over 70 percent until she reached the sixth form, Savage thought of herself as a slow thinker. The drawing lesson was her one joy, and a near perfect mark in drawing restored her self-respect. Two teachers encouraged her: the Art Supervisor, Miss Stuart, who visited Grade IV and singled out her drawing of a witch on a broomstick, and Ada James, the art teacher in the upper forms. For Ada James, Savage felt "respect, awe, and what amounted to veiled affection." Later, when Savage became a teacher, she felt grateful to James for having fought the entire School Board in order to establish a two-hour art period.

In the sixth form, Savage sat the McGill School Certificate Examination in art. She failed "brilliantly." Although, in her interview with Calvin, she makes light of her failure, it must have been a severe blow to her self-confidence. As a small child, Savage had told Minnie Clark: "When I grow up, I'm going to be an artist." Her aunt replied: "Well, that's all right, you can, but you must remember that you mustn't give in."

Savage remembered her aunt's advice. She applied to the school of the Art Association of Montreal (AAM). Not only was she accepted, but within a year she had won one of their scholarships entitling her to two years' free tuition.

The five years (1914-19) that Savage spent at the AAM - the ideas she encountered and the friendships she formed - shaped the course of her life. She herself has spoken vividly about the two teachers who inspired her, William Brymner, director of the art school from 1886 to 1921, and Maurice Cullen. From Brymner she learnt the "terrific importance of being connected to the world of art." Cullen, who had studied in Paris, brought them the "feeling of the Impressionist Group." As Savage recalled, what impressed her particularly about Cullen was "his complete absorption in what he was doing and his great love of the outdoor world. He just adored everything about nature."

At the AAM, Savage received a thorough grounding in drawing and painting. She worked hard and in her last year won the Kenneth R. Macpherson Prize for the best student painting.

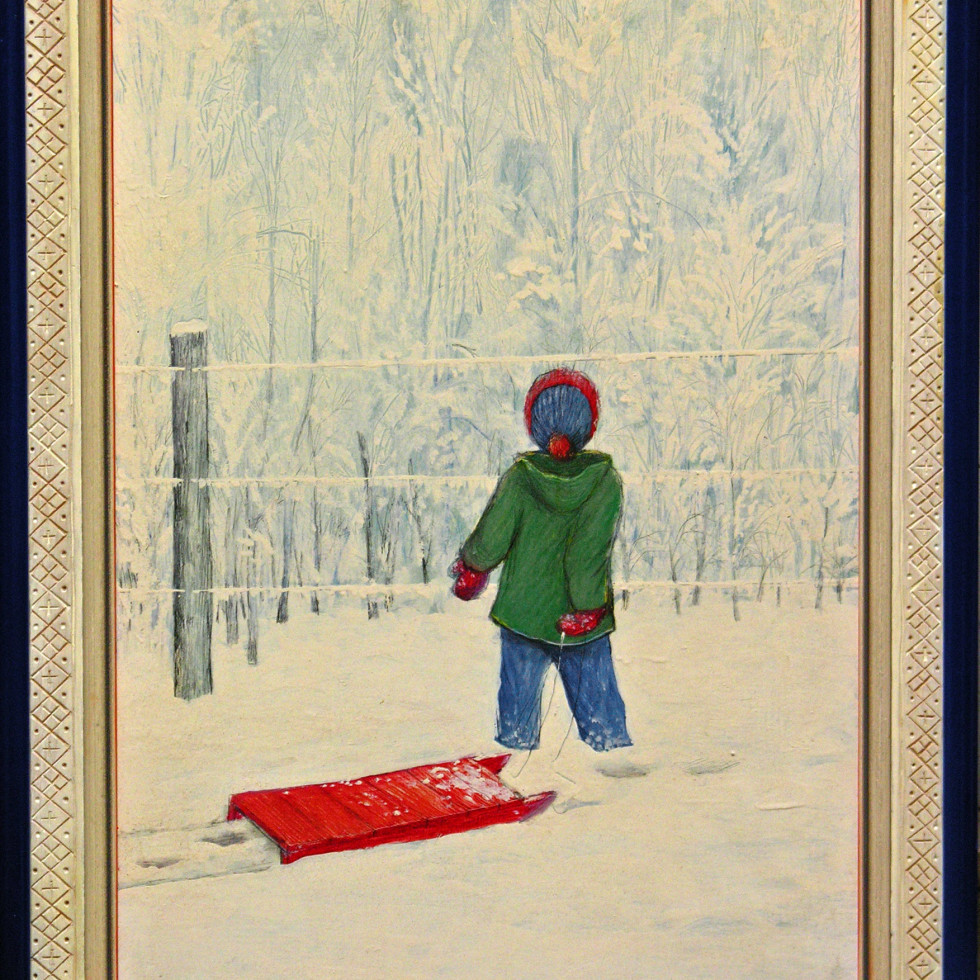

Savage's years at art school coincided with the First World War. Her twin brother Don, a second lieutenant, and an older half-brother were serving with the Canadian army overseas. On November 15, 1916, Don was killed on the Somme. When John Savage heard of his son's death, he immediately took his family up to Wonish. Queenie MacDermot describes how her sister, Anne, stood in the dining-room window painting the bare trees with tears in her eyes. (Both the sketch and the canvas painted from it, Lake Wonish (for Don), were featured in Galerie Walter Klinkhoff's 1992 Anne Savage Retrospective Exhibition).

The unexpected death of her brother increased Savage's determination to be an artist. As she told Calvin: "I was left with this feeling of trying to do something to make up for that loss." The idea of "carrying on" was prevalent during the First World War. Savage had heard it often from Brymner, who urged his women students to carry on for the absent men. For Savage, carrying on for Don also involved bearing some of the responsibilities that he would have borne. The family's finances had suffered during the war, with the decline of John Savage's business, Albert Soaps. So, Savage felt that she must not only paint as well as she could, she must also find some way of making her work pay.

Her first job was as a medical artist at Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue military hospital. According to Braide, Savage and Dorothy Cole were chosen from the AAM school to work for Dr. Waldron, a Minneapolis dentist. The two young women went with Dr. Waldron to the Christie Street military hospital in Toronto, and then to Minneapolis, where they spent their afternoons making drawings of facial reconstructions. In the mornings they studied commercial art at the Minneapolis School of Design.

On her return to Montreal, sometime in 1920, Savage moved back into 20 Highland Avenue, the modest two-storied house her father had bought in 1918. The year away from home had increased her self-confidence, however, and subtly changed her status within her family; she was no longer a student, but an independent woman engaged in building her own career. She soon found work at Ronald's Press. As she told Calvin: "I really thought I was heading for New York to be a great big commercial artist. I had no soul at all. I was only thinking how I could make my work practical."

In early 1921, Savage's life was transformed by a call from Dr. Silver, the head of the Protestant School Board, who offered her a job as a supply teacher. She began teaching art to the girls of the Commercial and Technical High School on January 10, 1921. Although she had no formal training as a teacher, she had some experience in teaching art to children. During the war she had gone to the McGill Settlement and started an art class for "little toughs off the street," as she described them. But teaching in a school environment was different. In the beginning she had no idea how to plan a course and simply struggled through one class at a time. Her principal, who was following her progress, was obviously satisfied, and in September 1922, when he moved to a new school on St. Urbain Street, he took Savage with him. At the age of twenty-six, she became art teacher at Baron Byng High School, a job she was to hold for twenty-eight years.

Savage had returned to Montreal at an opportune moment. In May 1920, several Montreal artists, inspired by the example of the Group of Seven in Toronto, formed an art association in order to show their work. At that period, Canadian painters were having great difficulty selling their work because the art dealers and private collectors favoured European painting. Unlike the Group of Seven, who shared a common aesthetic, the Montreal group was a heterogeneous association of men and women - all of whom were, or had been, students of William Brymner. The headquarters of the new group was a house on Beaver Hall Hill where Randolph Hewton and others had their studios. Savage, who appears to have been a founding member of the group, used to paint in one of the studios after school. According to her, there was a selfless spirit among the artists, who were inspired by A.Y. Jackson's call to "create a Canadian art for Canada."

On January 17, 1921, the members of the Beaver Hall Hill Group, as they called themselves, celebrated the opening of their First Annual Exhibition. Both The Gazette and La Presse covered the event, reporting A.Y. Jackson's speech and naming the nineteen artists-eleven men and eight women-who exhibited.

Despite this impressive beginning, the Beaver Hall Hill Group held only four exhibitions, including a joint show by students of the AAM and Savage's school children. Randolph Hewton blamed financial worries for the Group's early demise. For the women members, however, the spirit of the Group lived on. Friendships formed during Brymner's classes were rekindled on Beaver Hall Hill. And years after the studios were abandoned, the women continued to work together. They encouraged each other, shared news of art exhibitions, and offered constructive criticism of each other's work. At a time when women were having difficulty breaking into the predominantly male art world, they formed a valuable network.

Who were these women? When Savage talks to Calvin about her "little group" she is not necessarily referring to the original members of the Beaver Hall Hill Group as cited in The Gazette and La Presse. Apparently, several of the original members dropped out, leaving four-Anne Savage, Lilias Torrance Newton, Henrietta Mabel May and Mabel Lockerby-who became the nucleus of a new group. In 1966, when Norah McCullough organized an exhibition entitled The Beaver Hall Hill Group, she included ten women, the four mentioned above plus Prudence Heward, Sarah Robertson, Kathleen Morris, Nora Collyer, Ethel Seath and Emily Coonan. Since the exhibition, art critics have used the name Beaver Hall Group to refer not to the historical group but to these ten women.

All of these women, with the exception of Coonan, were friends of Savage's. During the holidays, Savage would visit Collyer at Foster and sketch in the Eastern Townships. After school, she would drop in for tea with Heward or Morris. Sketches would be brought out and critiques made. When Savage exhibited her students' work at Baron Byng, her friends flocked to see it. As she explained to Calvin: "There was a remarkable spirit. We telephoned one another 'Have you got anything? What are you doing? Can I come up and see it? Could you come down?' We had a swell time actually."

Savage carried the excitement that she felt about art into the classroom. One of her former pupils, Leah Sherman, now professor of Art Education at Concordia University, remembers the art room at Baron Byng as "a very particular kind of place." It was partly the atmosphere, the focus on colour and texture, and partly the realization that this was a place where the students; "own potentialities as individuals were emphasized."

Savage saw her role as that of an enabler. She would tell stories or suggest themes from Canadian history to stimulate her students' imaginations. At the end of her teaching career, Savage wrote: "The outstanding quality that a teacher must have is absolute belief in the power of the child to find his own way… no mistakes are possible, no criticism, only appreciation and delight in the doing."

This "child-centred" approach to teaching art was new in the 1920s. Arthur Lismer, who was appointed vice-principal of the Ontario College of Art in 1919, was calling for a similar approach. In the summer of 1922, Savage sent Lismer some of her students' drawings and received a letter of encouragement from him. Later, she visited his Saturday morning children's class at the Toronto Art Gallery. Savage says: "I owe Arthur Lismer a very great debt… I'll never forget the impression, going into that Gallery, and seeing it just filled with children with the most extraordinary feeling of enthusiasm going right through the group."

According to Sherman, Savage provided a positive role model for her classes, which, in the early years, were all girls. The students admired the way Savage dressed-not because her clothes were expensive, but because she had an eye for colour and style. Savage was an Anglo-Protestant from an established Montreal family, teaching in a neighbourhood made up largely of Jewish immigrants. Sherman suggests that the students, who were questioning the values of their European-born parents, were influenced by Savage's strong spiritual conviction.

Alfred Pinsky, professor of Painting and Drawing at Concordia University, was one of the first boys to join Savage's class. He admires the way Savage managed to incorporate the two aims of art education within one class: to stimulate the visual imagination of all the students and to extend the particularly talented pupil. As both Sherman and Pinsky observed, Savage was a great teacher because she never stopped learning. She recognized that "every day's teaching problem requires a new living solution."

Besides teaching and painting, Savage was carrying the responsibility for the household on Highland Avenue. John Savage died on June 24, 1922. Within three years, both Savage's sisters were married: Queenie to Terry MacDermott (1924) and Helen to Brooke Claxton (1925). Shortly before Helen's wedding, Savage wrote to A.Y. Jackson, saying: "I find weddings most upsetting affairs, but great fun." This wedding may have been particularly upsetting since it must have made the twenty-eight-year-old Savage reflect on her own situation.

According to her nieces, Savage had many male friends and at least one opportunity to marry, but she chose to remain single. A feeling of responsibility for her mother may have been one of the factors influencing her decision. But the most important factor was her commitment to painting. Furthermore, she was enjoying her work at Baron Byng and the independence it gave her. Marriage would almost certainly have entailed giving up her job, since married women in the 1920s were expected to devote themselves to their families.

In Anne Savage: The Story of a Canadian Painter, McDougall has written very sensitively about her aunt's relationship with the painter A.Y. Jackson. It may be that this was the deepest emotional experience in Savage's life. Although Jackson and Savage met in 1919 and corresponded from at least 1925 until her death, they saw each other infrequently. Jackson lived in Toronto, between camping trips and visits to his many friends. His unsettled way of life may have been one of the reasons why Savage rejected the rather tentative proposal he sent her in September 1933. Although her reply is not extant, Jackson's letter of October 8, 1933, suggests that responsibility for her mother was the overt reason for her refusal. Savage may also have suspected that close proximity to an artist as energetic as Jackson might threaten her individuality as a painter.

Both Savage and Jackson were inhibited when it came to expressing their sexual feelings. He often resorts to descriptions of nature when he wants to convey his tenderness for her. Only his letters of autumn, 1933, after their holiday with his cousins in Georgian Bay, suggest any sexual urgency. Her letters to Jackson present a running commentary on her life-Baron Byng, art exhibitions, family and friends-with only an occasional hint at deeper feelings. One letter stands apart from the rest. On June 18, 1944, about twenty months after her mother's death, Savage wrote suggesting that perhaps they could make a life together: "To seek one's own happiness is hopeless but to be able to help someone else would be worth while." Was this apparent altruism a disguise for her real feelings? Probably. On the other hand, Savage may have felt relief as much as disappointment when Jackson did not encourage her. Five years later, Jackson's niece, Geneva Baird, told Savage that the Jackson family would have welcomed a marriage between the two painters. To which Savage replied, "It would never have worked."

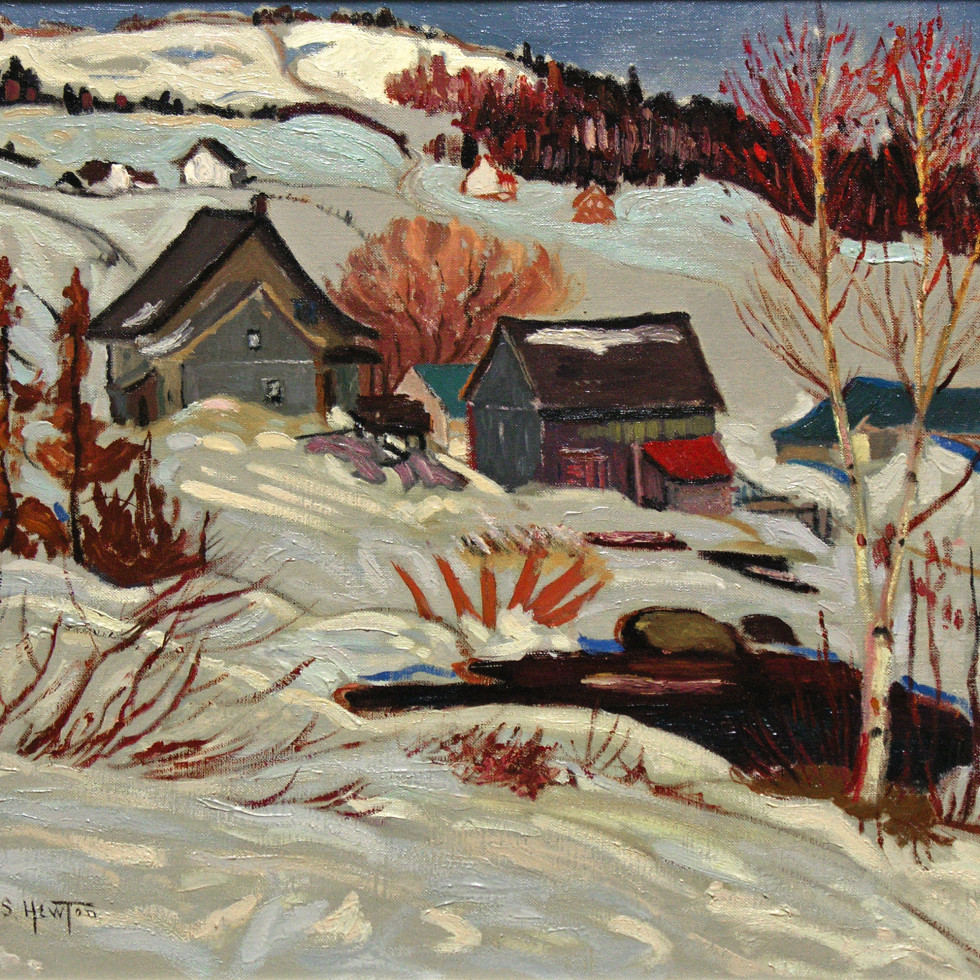

For thirty-two years Savage's life was regulated by the school terms. Most of her own painting was accomplished during the Summer and Easter holidays, spent largely at Wonish. In 1933, she built her studio at the head of the lake, between the original Horseshoe cottage and Kilmarnock, the log house her father had built for Don. She needed a place where she could work uninterrupted by her sisters and their families. She painted the view from her windows in all seasons, changing the angle and the composition. Sometimes she invited a nephew or niece to pose for her. In Portrait of Mary MacDermot, she places the young girl in a window with a view of the lake and mountains in the background.

The formation of the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) in 1933 brought Savage into contact with more artists. The new association, organized largely by Jackson, brought together the Group of Seven, their Montreal friends and a few painters from the West. Five of the Beaver Hall women, including Savage, became founding members of the CGP. Savage was frequently on the executive of the Montreal branch. Meetings of the branch could be quite stormy, since strong personalities like Arthur Lismer, Louis Muhlstock and Fritz Brandtner often clashed. Marion Scott, an individualist, found Savage a little too dominating and resented her insistence, during the Second World War, that members paint war paintings.

Savage's busy schedule did not leave her much time for traveling. In the summer of 1924, however, she visited Europe. The oil sketch of Concarneau Square in the Klinkhoff Gallery's exhibition is one of the few paintings that has survived from this trip, but Concordia University has many drawings of French towns, Oxford colleges and unnamed English churches.

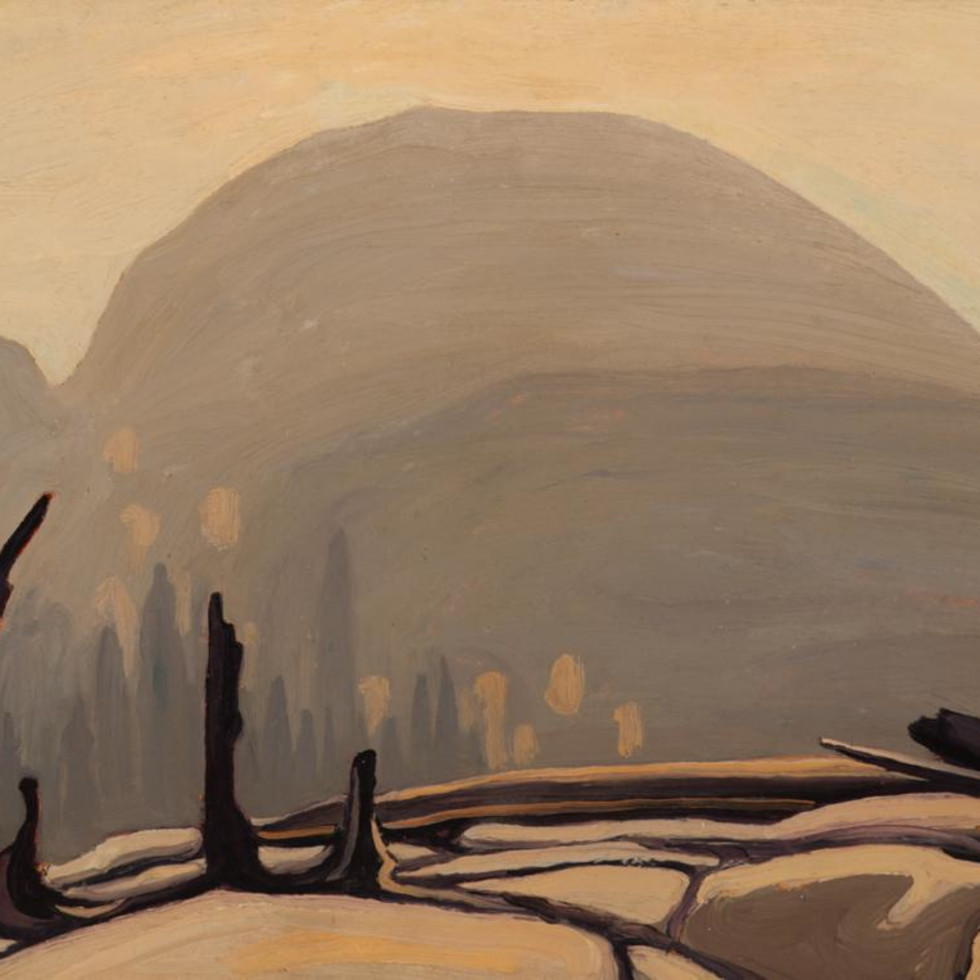

In 1927, she traveled to the Skeena River, British Columbia, with the sculptor Florence Wyle and anthropologist Marius Barbeau. The purpose of the trip was to record the deteriorating totem poles before the engineers began their work of restoration. As McDougall has suggested, the excitement of the long voyage into the interior made a vivid impression on Savage which is reflected in the intensity of the sketches that she brought back. In her canvas Paradise Lost (Temlaham, Upper Skeena River, BC), Savage isolates the essential qualities of the scene, the majesty of the mountains and rhythmic sweep of the river.

Savage made two more trips to the West. In the summer of 1937, she gave classes for art teachers in Edmonton and Calgary, and in 1949 she taught at the Banff School of Fine Arts. Although she managed some nice contrasts of light and dark foliage in Whisky Creek, BC, Savage did not enjoy painting in the West: "I didn't like the West. No. The West for me was too vertical… the lead in is what is the beauty of the Quebec landscape. In the West you get nothing but a repetition of high cliffs, high trees, everything just went up and up and up."

In 1937, Savage was invited by Dr. C.F. Martin, the new president of the Art Association of Montreal, to form a morning class for children. About 100 pupils, recommended by forty Montreal schools, gathered in the Sherbrooke Street gallery to draw, paint, and model in clay. Ethel Seath, the art mistress at The Study school, taught the clay modeling. After spending five days in the classroom, these women devoted their Saturday mornings to showing children the joy of art. The classes were so popular that volunteers, including Alfred Pinsky, were recruited to help teach. Savage's involvement decreased after Arthur Lismer came to Montreal in November 1940, to supervise art education at the AAM.

Between January 6 and February 24, 1939, Savage gave eight talks on Canadian art on CBC radio. She began with one, which linked Canadian painting to the English landscape painter John Constable, and ended with three on the Group of Seven and its successors. In the 1950s, she lectured on women painters to several Montreal women's clubs. Her lecture, "Women Painters of Canada," discuss the contribution of the Beaver Hall Group and singles out her friend Prudence Heward and the western painter Emily Carr as the "two stars on the horizon."

In 1948, Savage was appointed Assistant Art Supervisor for the Protestant School Board. Although she continued to teach at Baron Byng, her new duties made the greater demand on her imagination. As she explained to Jackson in her letter of October 5, 1948:

"Never shall I experience the joy and excitement of real creative teaching as I did at Byng, when the staff was it its peak, when Dr. Astbury was principal and six other good friends were there. They have gone and the joy seems to be waning, so maybe it is better that I slip out."

The following year Savage spent fewer hours at Baron Byng and, in 1950, took over as Art Supervisor, devoting herself full time to classroom visiting and administration. Recognizing that the elementary school teachers needed help in teaching art, she started classes for them at Baron Byng.

Even after her retirement in June 1953, Savage continued to be involved in education. From 1955-59, she gave a course in Art Education at McGill University and, in 1955, organized visiting lecturers for a course on "Art in Our Life" at the Thomas More Institute. She spent more time at her easel and put together a small exhibition at the YWCA (1956). In a letter to Jackson she expressed her gratification at having made ten sales-a "windfall" which would enable her to bring water into her studio at Wonish. Savage's joy at the sales is understandable, since juried exhibitions at this period tended to overlook figurative painting in favour of abstract expressionism. On April 21, 1961, after attending the Spring Exhibition at the Montreal Museum, she wrote Jackson about her disappointment at seeing so much of the same type of work. "My own painting looks like a fish out of water, as Lilias (Newton) says we are both practicing a lost art - portraiture and landscape."

Savage's family was very important to her. She participated joyfully in picnics and singsongs at Wonish and welcomed the family to Highland Avenue at Christmas. With the help of Margaret English (Gigi), Savage cared for her mother Lella, who died in 1942, and provided a home for three nephews in succession, while they attended McGill University. When Gigi became bedridden, Savage, who looked on her former nanny as one of the family, nursed her until the end. Such devotion takes its toll. Savage's last years were a courageous battle against arthritis and cancer. There were occasions for rejoicing, however, such as the two reunion concerts at Baron Byng. For the second concert, in 1968, Savage arranged an exhibition of her students' paintings, which she had carefully preserved. The following year, she attended the opening of her Retrospective Exhibition at Sir George Williams University. Anne McDougall describes a radiant Savage, supporting herself with a cane as she thanked her former students for organizing the exhibition. It was her "last performance." She died March 25, 1971.

Anne Savage was predominantly a landscape painter. The portrait of William Brymner (reproduced in McDougall, facing p. 64), painted while she was still a student, suggests what she might have achieved in the genre. Yet, in her maturity, the only portraits she painted were of her family.

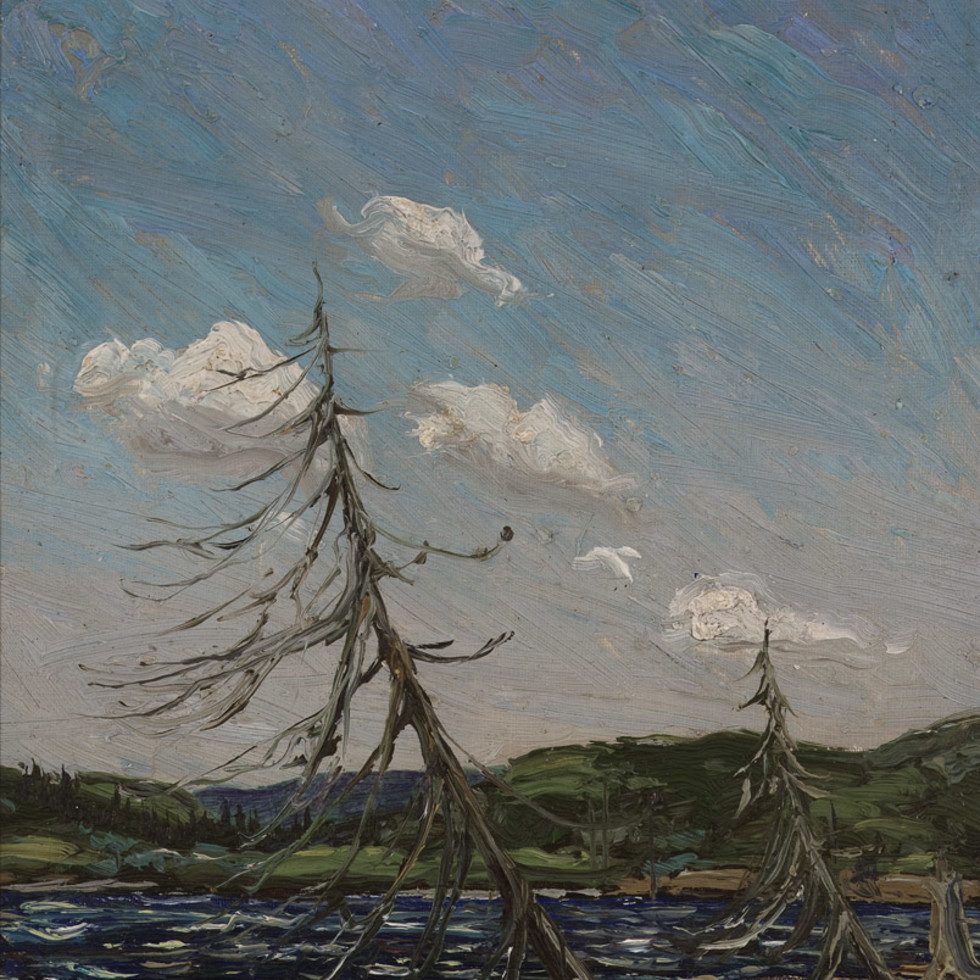

Savage found her subjects in the scenery she knew and loved, the lower St. Lawrence and Lake Wonish. In the tradition of the romantic poets, she endowed nature with spiritual qualities. Her personal experience of Wonish as a source of healing, combined with her religious faith, led her to emphasize the benign aspects of nature. In Quebec Farm (c. 1935), for example, the rounded hills, which echo the bending female figure in the foreground, suggests a harmony between the worker and her surroundings.

Even an early canvas like Lake Wonish (for Don) (c. 1916) shows Savage's ability to impose a design on nature. As she explains to Calvin, the Laurentians presented her with a challenge, because she had to find her own composition:

"You can go down to a fishing village and the thing is right there-there's nothing to do other than to do it. But if you're faced with a forest that you have to unravel a bit and you have to search around and find your plains and your hills, and model it up that way, it takes a lot more looking."

Janet Braide draws attention to Savage's skilful use of curved lines, which give rhythmic tension to her work. In April in the Laurentians (c. 1940), Savage creates an intricate interplay between the vertical curves of the birch trees and the horizontal strips of melting snow. In The Plough (c. 1931), she builds up a rhythmic composition of green swirls, brown furrows and undulating hills, against which she poses the plough. Its soaring lines, which cut diagonally across the landscape, suggests the power of the human spirit to contend with nature.

Although Savage remained a figurative painter, her later work shows a movement towards greater abstraction. Braide illustrates this tendency by comparing a series of sunflower paintings, starting with Autumn (c. 1935), in which the dark flower heads are set against a sunlit landscape, and ending with Sunflowers and Lake Wonish (c. 1968), in which the background is reduced to geometrical shapes.

Artists and art critics, starting with William Brymner, have commented on Savage's subtle handling of colour. Her palette for Autumn, one of her strongest paintings, is similar to that of The Plough: warm oranges and browns, with a range of greens and touches of violet. During the 1950s, she lightened her palette and experimented with painting on masonite, whitened with gesso. In Laurentian Landscape (c. 1960), soft yellow and greens against a white background create an effect of light and space.

Alfred Pinsky has spoken of the contradictions that Savage experienced daily between the way art was perceived in her middle-class milieu and the way she perceived it-between art as decoration and art as a driving force. Could Savage have extended herself further as a painter if she had broken out of her middle-class milieu? There is no simple answer. In order to devote herself entirely to painting, Savage would not only have had to leave home, she would have had to give up teaching. And for Savage, teaching was not just a means of earning her living, important as that was, it was an "unparalleled creative incentive."

When I began writing about Savage, I wondered how she managed to combine her two careers and also fulfill the responsibilities, largely self-imposed, of her personal life. I now recognize that her various roles were interdependent. She drew strength from many sources, including the example of Minnie Clark, the friendship of the Beaver Hall women, and her affectionate relationship with A.Y. Jackson. But her greatest source of strength lay within. Anne Savage believed in art as the expression of what was highest in the human spirit. Whether she was painting or awakening others to the beauty around them, she worked with self-abandonment, intensity, and joy.

© Copyright Barbara Meadowcroft & Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc.

Dr. Barbara Meadowcroft is a Research Fellow at the Simone de Beauvoir Institute, Concordia University. She has written catalogue essays for the Mabel Lockerby Exhibition (1989) and the Sarah Robertson Exhibition (1991), both at the Walter Klinkhoff Gallery, and written a book on the Beaver Hall Group.