William Raphael

"The faithful transference of truth and beauty is not a thing that depends on fashion […]"

William Raphael

"The faithful transference of truth and beauty is not a thing that depends on fashion […]"

William Raphael

by Sharon Goelman, M.F.A.

William Raphael was the first Jewish professional artist to establish himself in Canada. He was a sensitive and modest individual with three loves: his family, including his dogs; nature; and art. Raphael is best known for his exemplary portraits and lively Canadian genre scenes.

Like his older Canadian contemporaries, Paul Kane (1801-1871) and Cornelius Krieghoff (1815-1872), Raphael gained recognition for capturing the habitant and First Nations way of life in his new land. His exhibited works were favourably reviewed and he was credited as being "one of the cleverest artists, an old favourite to Montreal" and "perhaps one of the most thoroughly educated historical painters in Canada." Although less known for his quiet landscapes, religious paintings, still lifes and anatomical drawings for medical lectures and publications, or for his restoration of church canvases, he was also regularly acknowledged in the newspapers for his contributions to the field of art education, both in public institutions and in his own private school.

Raphael was a product of his background and training, for which he was highly respected early in his career and well into his middle years. However, tragically, at the climax of his artistic output there was a shift in aesthetic tastes that affected his career and his previous momentum. He suffered greatly as a result.

Formative years in Berlin

Raphael was born in 1833 in the tiny town of Nakel in Prussia, sixty kilometers from Berlin, where his parents, the Rafalsky family, Orthodox Jews of Polish descent, had settled.

In larger cities such as Berlin, where culture abounded, a gradual emancipation of Jews and a growing movement of Reform Judaism evolved during the 1840s and 1850s. Raphael's ambition to become an artist corresponded with this new liberalization of German Jewish life.

In 1850, when he was seventeen, Raphael arrived in Berlin to study. He wrote: "Different is the world with each new step away from my parents' home… how the sun is cold… everything seems so foreign to me." His personal writings from that time reveal a sensitive young man with strong emotions, intensely interested in music, literature and classical history. He first noted his dues to the Royal Academy of Berlin in 1851, when he wrote in his diary, "I had lessons with professor Wolff on November 4, 1851." But on October 8, 1955, he states, "I left the Atelier in order to go to the painting class of the Academy," which indicates that at this point he was possibly studying with a private teacher or professor at an atelier, yet also with others at the Academy. His sketchbooks contain drawings from plaster casts in attempts to grasp form, light and shadow, copies of works by proven masters, sketches from everyday life, as well as anatomical studies. Such exercises reflect the rigid academic training for which the Royal Academy of Berlin was known, to which Raphael would unflinchingly adhere throughout his career and use as an approach when he, in turn, taught art.

Raphael was born only six years before Louis Daguerre (1789-1851) publicized his photographic process, yet by 1850-1851, when Raphael was studying in Berlin, this invention had probably already influenced the style and philosophy of the teachers who taught him. His teacher, Wolff, was likely the portraitist, Johann Eduard Wolff, at the Royal Academy of Berlin. We cannot trace with certainty the style of Wolff during the period when the life of student and teacher overlapped. However, the oeuvre of the portraitist, genre and painter of historical scenes, Karl Begas (whom Raphael would refer to as his professor repeatedly once in Canada) left a lasting impression on Raphael's aesthetic values and approach to interpreting nature.

Begas veered away from earlier overtones of the Nazarene branch of Romanticism and turned towards Realism, becoming more objective in his interpretations. This objectivity was probably tempered by his study of current experiments with photography and the new freedoms inherent in the industrial age. Both Raphael's teachers, Begas and Wolff, earned recognition as minor masters at the forefront of the Realist Biedermeier or Early Naturalist movement in Germany, which was often opposed to the philosophical or spiritual side of the Biedermeier Romantics or the Northern German Romantics.

A Fresh Start in the New World

After the deaths of his parents, Raphael decided to join the great wave of emigration that started mid-century in Germany during what was a difficult economic period of unemployment, poverty and displacement, especially for artisans. His decision to come to Canada was bolstered by a support system of friends and family, including a brother in Montreal. On December 22, 1856, Raphael disembarked from the steamship Borussia in New York City, where he stayed for four months before leaving for Montreal. He arrived in Montreal, his new home, on April 23, 1857.

Raphael loved the countryside and the serenity of nature and enjoyed painting landscapes, however, he had to make a living in the city, where he earned his income mainly through commissioned portraits. During his first year in Montreal he found sitters for portraits, as he had earlier in New York. In between slack periods of work in Montreal, he traveled to Quebec City, Trois-Rivières and later to London and Windsor to seek further commissions and experience the many characteristics of the Canadian landscape.

The Relationship Between Photography and Portraiture

We learn from ledger payments listed in Raphael's diary that by 1859 he had a regular income from Notman's photographic studio. Indeed, he later referred to that experience: "When I arrived to this country, a stranger to the people and language, Mr. Notman proposed to me an engagement for a year, to paint for him the portraits taken by photography, and I gladly accepted." Raphael was probably still working at Notman's in 1860, but may have been displaced later that year, when Notman hired John Fraser to manage a number of full-time artists. Raphael also worked with A.B. Taber, another photographic firm. A canvas in the National Gallery of Canada of the McFarlane Children, signed jointly by James Inglis, photographer, and W. Raphael, dated 1871, suggests further collaborative work in photography and portraits. Although lucrative, this practice may have narrowed his freedom of approach towards painting portraits in years to come. The fact that he shared quarters with A.G. Walford, photographer, in 1881 indicated that he continued to depend on portraiture for his livelihood.

Certainly during his earliest years in Canada East, as Quebec was known until 1867, Raphael painted many portrait commissions from a cross-section of the Montreal community. Among the many portrait references found in his sketchbooks from the years 1857 to 1859 was one of a Mr. Hermann Danziger, in whose home Raphael resided as a boarder in 1861 and whose fifteen-year-old daughter, Ernestina Danziger, Raphael would marry the following year.

Between 1863 and 1886 the Raphaels produced nine surviving children, likenesses of whom would be incorporated into their father's sketchbooks and paintings. One son, Samuel, followed in his father's footsteps; he became an artist in New York City.

During the 1860s and early 1870s, Raphael painted mostly genre scenes, portraits and a limited number of landscapes, acquiring favourable mentions in the press regularly. However, throughout the depression years of 1873 to 1878, it was his affiliation with photographers and his ability to capture sitters' likenesses freehand or from photographs that provided Raphael with many opportunities not available to his contemporaries. It was during these years that his reputation as a portraitist grew amongst the elite French-Canadian clientele, including families such as Desjardins, Panneton, Paré, Souligny de Vinet and Provost.

Research has brought to light portraits by Raphael of prominent figures who contributed greatly to Canadian society. In the medical and religious communities, they include Dr. Louis Edouard Desjardins, the first French-Canadian ophthalmologist in Montreal; Dr. Aaron Hart David, the first Jewish physician in Canada and a descendent of the first Jewish family to live in the Province of Quebec; Dr. Francis W. Campbell, Hart David's successor as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Bishop's University; Reverend Dr. Abraham De Sola, Professor of Oriental Languages at McGill University and Reverend of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue; and Cannon Joseph Octave Paré, Secretary to Bishop Bourget.

Various examples of Raphael's portraits of politicians, businessmen, military figures and fur traders who helped build the region now known as Quebec are found in the McCord Museum and in the Château Ramezay. Raphael's portraits of Governor Generals were reputed to have hung in the original Parliament Buildings. An oversized poster-type photograph of a full-length painting of Gladstone and Laurier at Hawarden Castle, signed by Raphael and dated July 10, 1897, show the two Prime Ministers arm in arm. To date, the original canvas has not been found.

Raphael painted formal bust portraits of immediate family members and a self-portrait as keepsakes for his home and those of his children. Several of these detailed works were inspired by photographs. They are indicative of the delicate brushstroke and subtle, non-dramatic manner in which Raphael treated his subjects and surfaces. In contrast to the formal portraits are Raphael's more loosely painted full-length studies of his wife and children. Examples of these include Lady in Pink Knitting Outdoors, Boy with a Top (1879), Fletcher's Field, Montreal, (1880), and Study of Boy, Ducks and Cats (1884). When using his own children as models, Raphael exhibited a livelier approach. The figures' suggested movement and frolicking mood differs from the concerned-looking Irish Immigrant (1870) in tattered clothes and the serious posthumous tribute Portrait of a Boy (1875), dresses in a tartan kilt.

Genre Subjects and the German Biedermeier Influence

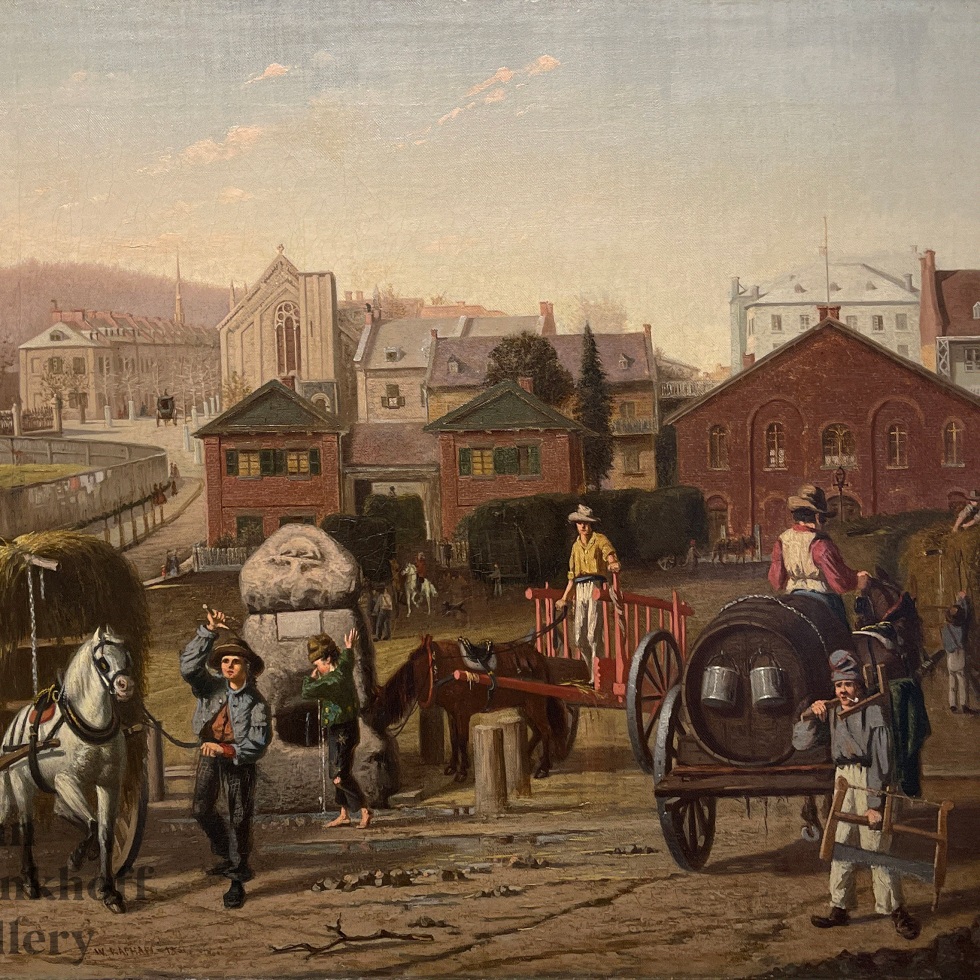

In his genre scenes, Raphael strove to document the more romantic aspects of Canadian life, as seen through the eyes of an immigrant anxious to record details of people's appearances and activities. He incorporated into the compositions a feeling of harmony, accomplished through formal, ordered realism. He often based his scenes on carefully prepared sketches executed on location, yet he lent to them a levity and casual air through relaxed, sometimes witty participants. This is demonstrated in his most illustrious genre painting, Behind Bonsecours Market, Montreal (1866), formerly titled, Immigrants at Montreal, where, through structured light, the artist captures detailed aspects of the environment and society at the Montreal harbour amid the freshness of spring.

Raphael placed himself right in the centre of the sunny harbour scene located in the back of Bonsecours Market. He clutches his hand-luggage in his right hand and his artist's portfolio and precious keepsake, his family's silver candelabra, in his left. Many preliminary sketches have been found that relate to this complex painting. The luminous treatment of the boats, the distant water and the haze on the right rival superb Luminist examples. The winter counterpart of this painting, titled Bonsecours, documents the activity in front of the marketplace along St. Paul Street and reveals a lively sense of anecdote and humour.

Raphael painted Habitants Attacked by Wolves in 1870. He must have relished the concept. A similar undated oil sketch, Habitants Chased by Wolves; another smaller oil, Pursued by the Wolf Pack, (1869); and a chromolithograph identical in appearance and size to the painting completed in 1869, are all based on the same romantic theme - three adults in a one-horse drawn sleigh being chased by ferocious wolves in a threatening winter landscape. One senses the urgency of the habitants trying to escape these wild animals at their heels as they try to race ahead of an oncoming storm. The romantic notion of the chase was particularly appealing to the German artist's love of adventure. In several paintings, he depicted three jovial young boys rambunctiously racing through the snow in similar threatening winter compositions, with a dog-drawn log sleigh, only this time sans wolf pack behind. One such example is Winter Fun (1878). In another version, Avant la tempête (1869), a mother and child lag behind the group in deep snow.

After examining Begas' work and Canadian scenes by Raphael, it becomes apparent that Raphael's oeuvre and subject matter reflects his teacher's example and link to the Realist Biedermeier. Raphael was fascinated by the pomp and ceremony of official events, groups of people in contemporary costumes, and well-known monuments or buildings. This is exemplified in his painting St-Jean-Baptiste Parade Outside the Montreal Bank (1872). Here the artist fully documents the colourful annual event of Quebec's Catholic community and the detailed classical features of the bank.

Habitants and First NationS - Close-Ups of Individuals

Raphael never lost his interest in capturing the habitant in his toque, long jacket and hand-woven belt, the ceinture flechée, smoking his pipe, whittling a piece of wood, lacing a snowshoe, grinding corn, hunting in the woods or cutting tobacco. Various versions show the habitant's wife working in the kitchen at her spinning wheel, usually in front of a wood stove, with an oval rug woven from rags on the floor below. Seated Habitant Smoking His Pipe, painted in watercolour in 1872, and Habitant Mending a Snowshoe, a watercolour executed in 1873, were made into 1,000 photo-lithographs and comprised part of the National Gallery of Canada's set, The First Portfolio of Canadian Watercolours, lithographed by Cambridge Press of Montreal in 1950.

In addition to habitant scenes, Raphael searched for authenticity of social strata, customs and clothing of the First Nations. Princess Rose Taieronhoete depicts the Kahnawake Reserve Chief's wife in ornate dress, feathered headpiece and jewellery while Two Indian Women (1873), portrays a young girl seated next to an older woman. Large shawls cover their heads and shoulders as they wait to sell wares from their hand-woven baskets.

Landscape

Raphael's landscapes elicit the harmonious quietude of Canadian nature. The artist traveled to a variety of regions as early as 1858 in order to experience vistas in various parts of Quebec and Ontario. Throughout his remaining years in Canada he continued to record scenes at varying locales, including Lachine, the Laurentians, Sherbrooke, St-Grégoire, the Eastern Townships and New Brunswick. Outside of Canada, he sketched in the Adirondacks, New York, Lake Champlain, Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia and even Scotland, where he was lured by the beauty of Scottish castles and mountainous regions as early as 1865.

In all, Raphael sought peaceful environments where he could connect with the mood of forests, woods, waterfalls, mountains, cliffs, swamps, rivers and lakes. He relished evidence of humankind's existence in nature, and recorded their site-specific creations… churches, castles, old mansions, bridges, steamships, boats and canoes. Stark daylight is magnificently rendered in scenes such as With the Current (1892), where a leisurely couple relaxes in a boat amid nature's greenery, and in The Lily Pond, Laurentians (1911), where the lily pads, water and surrounding foliage, all drenched in sunlight, seem palpable. The silence of a beautiful summer evening is captured in both Church at Tadoussac, Sunset (1879), and Près de Sherbrooke (1898). The varied brushstroke, colour, texture and treatment of light are all convincingly executed in these truly Canadian environments.

Certain paintings of Quebec scenery by Raphael provide invaluable documentation. Delightful to the historian are Raphael's Pointe-au-Pic, Murray Bay encampment scenes, where he sketched the specific style of the Montagnais First Nation's birch bark wigwams and Maliseet canoes before they became extinct. Two such canvases, one in the collection of the McCord Museum, Three Montagnais Wigwams on the Shore Beneath the Cliffs at Pointe-au-Pic, Murray Bay, and a second, The Last of the Wigwams, are referred to in the foreground of the dramatic nocturnal moonlit scene that won Raphael his acceptance into the Royal Canadian Academy in 1880. Titled Indian Encampment on the Lower St. Lawrence, it was painted in 1879. Unequaled in its intensity of mood, it is much larger, darker and more mysterious than the smaller studies. This diploma piece and the many related Murray Bay pencil sketches dating to the late 1870s are found in the National Gallery of Canada.

Prints and Illustrations

Some of Raphael's original works were made into various types of lithographs to make the imagery of Canadian life available to the broader public. Others were made into illustrations for the readers of travel books. Raphael's anecdotal oil, The Early Bird Catches the Worm, 1868, a work demonstrating poetic justice and humour, was made into a chromolithograph (coloured lithograph), published by Roberts and Reinhold in 1869. It was touted to be the "first attempt in Canada of the chromo process." His dramatic subject Habitants Attacked by Wolves was also made into a chromolithograph, this time by Burland L'Africain and Company for distribution to the Art Association of Montreal's subscription members in 1870. In 1881, the same institution made photoprints from Raphael's Head of an Iroquois Chief, Caughnawaga and Scene at Murray Bay and presented them to their members as a bonus. That same year, Lucius O'Brien invited Raphael to submit four illustrations of individual habitants for the two-volume travel book Picturesque Canada, to be published in 1882. Correspondence from O'Brien's arch-rival John Fraser indicates that Fraser also asked Raphael for figure studies for a book that he intended to produce, but which never materialized.

Still Life and Floral Studies

Raphael painted still lifes of hanging fowl and fish and symbolic floral studies, which were fashionable in the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries. He excelled at flowers. The Art Gallery of Vancouver has in its collection a close-up view of a densely grown patch of Hollyhocks (1908), inspired by the artist's personal garden. A black cat, hardly noticeable from behind, peers at the viewer through the tall, sun-lit red, white, pink, yellow and purple flowers. This painting is executed in a lighter palette with boldly-applied impasto paint and a livelier brushstroke than the more traditionally painted interior still life, Peonies in a Vase, where the pink flowers fill up the foreground of the composition, and fallen petals and leaves remind the viewer of the effects of time passing.

Religious Paintings

Raphael painted a variety of religious scenes for various Catholic orders in Montreal. Bishop Bourget recommended him to the Sisters of several orders, who commissioned him to interpret works by their favourite European artists, or in some rare cases, to create his own. Raphael interpreted a Ste-Famille grouping (The Holy Family) after a 1662 Abbé Hughes Pommier work executed in 1882 for the Congrégation Notre-Dame. It is still on view at Ferme St-Gabriel in Montreal. Among other subjects, he painted annunciation scenes and guardian angels. To this day, Raphael's almost ten-foot high The Blessed Virgin (1909), blesses those who enter the main chapel in the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Ste-Anne in Lachine.

Raphael the Teacher

Raphael's contribution as a secondary level teacher in Montreal was considerable. He taught art privately and at various institutions. In 1866, he advertised himself as an "artist and teacher of figure and landscape painting," and he would continue in this vein over the years. He admitted in an interview that "without teaching no artist could live here. If he depended upon the sale of his paintings he would starve… due to a small buying class and a taste for French and Dutch art above good Canadian work."

Raphael devoted much of his career to teaching in both the English and French communities, despite his difficulty with the French language. The English schools he taught at were the Villa Maria Convent (bilingual), Montreal High School, the Art Association of Montreal and his own private art school. The French Schools were those affiliated with the Sisters of Ste-Anne.

By 1879, there was a sense of hope and stability at the Art Association of Montreal. That year, its new building on Phillip's Square was opened by the Marquis of Lorne. There was also a feeling of promise surrounding the formation of the Royal Canadian Academy (R.C.A.), modeled after the Royal Academy in Britain. The Marquis and a hard-working nucleus of artists from the Art Association of Montreal and the Ontario Society of Artists, under the able leadership of President Lucius O'Brien, succeeded in creating the Royal Canadian Academy in 1880.

These were exciting times, perhaps the most animated in Raphael's career. The Academy and the Art Association became closely aligned and soon there were plans for an art school. Raphael, one of the charter members of the R.C.A., was given the honour of teaching the first course in Figure Painting and Drawing to advanced students. The school opened in 1881. For the next slate of courses, Raphael took over Allan Edson's class in Composition and Landscape and taught an additional course in Figure Painting and Drawing from the Antique.

The following year, however, despite the fact that there was no one to replace him, Raphael's contract was not renewed.

In 1883-84 Robert Harris was hired to fill Raphael's former position until 1886, when William Brymner stepped in to run the school. Both revamped the courses along "French Studio" lines. Their principles were diametrically opposed to traditional academic ways.

Trouble at the Art Association and the R.C.A.

In the 1860s, Raphael had prided himself for being the first in Montreal to introduce drawing from the plaster cast and from life. It seems that it was only by the mid-1880s that he began to hear rumblings through students and friends visiting the Art Association that this teaching methods of studying plaster casts and anatomical parts were antiquated, and that the new "French Studio" methods espoused by Brymner demanded that the artist derive inspiration directly from nature, with "life and unity… the first essentials." All formulas that encouraged copying or imitation in any form were considered sacrilege. Raphael resented the new guard's criticism, but now realized why fewer of his submitted works were being accepted for exhibition of the Art Association. A man of integrity and devotion to his craft, he defended himself publicly in 1886. "The faithful transference of truth and beauty is not a thing that depends on fashion… I hope to do good work for many years to come, and finally to see the public of this city lend through the learning generation, to an appreciation of sound and faithful art, in place of the superficiality and 'paint' which seems up to the present to satisfy its taste."

Back in 1882, Raphael had decided that if he could not teach the students at the Art Association school, he would form his own. To that end, he repeatedly asked colleagues on the committee at the R.C.A. to help him gain financial backing from annual grants supposedly set aside by the R.C.A. for the promotion of art education in the Dominion. But each year his colleagues at the R.C.A. had other plans for the funds.

Somehow, by 1885, Raphael managed to open his own school on the second floor of 1310 Ste-Catherine Street, while still hoping that grants would be forthcoming. That first year he had thirty pupils enrolled. In the winter of 1886 he had "twice as many" students as Brymner at the Art Association. He crowded them into one room and taught drawing and painting "from nature or the object" and eventually from live models, whom he would dress up in interesting costumes. By 1887 he expanded to include a second room for the more advanced students. Still no grants came. His student exhibitions, however, were a huge success; they "were all worth seeing and all show[ed] the taste and skill of the pupils and the proficiency of Mr. Raphael as a teacher."

Raphael missed the support of his old colleagues, who were by now living in other cities or deceased. Henry Sandham and John Fraser were both in Boston at this point. Otto Reinhold Jacobi was en route from Dakota to Montreal. Allan Edson was living in the Eastern Townships. Adolphe Vogt had died. During what should have been the apex of his career, he felt alone and feared losing the reputation he had built over the previous three decades. He had paid his dues to all the art societies. Why was there now no support for him when even in the last several years he had been showered with so much recognition?

Indeed, the years 1879-1882 seemed to represent the peak of his career. In 1879, he was accepted into the Ontario Society of Artists; he exhibited with the Royal Society of Artists in London, England; he produced his major canvas First Nations Encampment on the Lower St. Lawrence; and he was invited to teach at the Convent of the Sisters of Ste-Anne. He received acclaim for his anatomical drawings from Dr. William Osler and some were published in two major medical journals. In 1880, the Marquis of Lorne complemented Raphael by purchasing one of his habitant paintings, painted that year; the new Bonsecours scene that he had just completed received wonderful reviews; he was one of the founders of the R.C.A. and was inducted as one of the esteemed original members, seemingly through the support of his colleagues at the Art Association and the Ontario Society of Artists; he was respected enough to be offered a teaching post at the new Art Association classes; he was invited by Lucius O'Brien, President of the R.C.A., to prepare illustrations for the proposed book Picturesque Canada; and in 1882 he considered himself to be a proud founder of the National Gallery of Canada, where his diploma painting now hung.

Understandably, the sudden criticism was an upsetting shock. Raphael had worked tirelessly toward the establishment and maintenance of high standards of every important art association and institution that gave voice and exhibition opportunities to artists in Canada from 1860 into the early twentieth century. He had shown his work and participated in the Art Association from 1860 and the Society of Canadian Artists from 1867.

As for his favourite organization, the Royal Canadian Academy, he had put his greatest energies into its formation, attending Council and General Assembly meetings regularly. Thereafter, although no longer in the inner circle, and despite his discomfort with Brymner by the mid-eighties, he patiently continued to sit on Council until 1894, when it became apparent that his situation would not change. Nor would the attitudes of the controlling few at the Art Association and the R.C.A. In 1896, after sixteen active years, Raphael resigned from the R.C.A.

Raphael must have made his reasons for leaving clear to J.W.H. Watts, Curator of the National Gallery and one of the people present during the March 13, 1896 meeting at which he handed in his resignation. Watts wrote in his personal diary that Raphael "resigned lately from the R.C.A. on the grounds of injustice by Brymner monopolizing the criticizing [of paintings submitted for acceptance] and the refusal of the R.C.A. to give a grant to his private school." About Brymner, Watts wrote elsewhere: "He has a high appreciation of superiority over many of his fellows… fond of criticizing and pretty sure when on the buying committees to have all his pictures in the line, which is often a cause of bitterness. Poor Raphael, an old member, used this as his reason for resignation."

Earlier, Raphael had joined the Pen and Pencil Club of Montreal in 1890, but resigned in 1891, possibly because the same R.C.A./Art Association clique had become active there too, and his displeasure with them was brewing. In 1904, Raphael was appointed a member of The Council of Art and Manufacturers of Quebec. Outside of Canada he was no longer participating in expositions. He had exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, the Royal Society of British Artists in 1877-1878 and at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in 1886. Prior to 1886 Raphael had worked and exhibited with every respected official art group in Canada and with some beyond its borders.

The years after 1883 were the most difficult period in Raphael's artistic career. However, his love of teaching saved him. He was happy running his own school and was comfortable in the French-speaking institutions in which he taught before and after the Art Association school.

The Sisters of Ste-Anne in Lachine in particular were deeply respectful towards his gentle manner and formal teaching methods. Upon his retirement in 1910, they arranged to purchase from him his plaster casts (except for the nudes). As well, Sister Hélène-de-la-Croix held him in such high esteem that, despite her position as head of the Art Studio at Ste-Anne's, she was still bringing him works for approval in 1911. In 1912, for New Year's, the congregation surprised Raphael with a likeness of himself, an oil portrait painted by Sister Hélène-de-la-Croix that he was pleased to receive and gratefully acknowledged with thanks. "I have to compliment the artist who painted it, it is well rendered and artistically treated."

Successful Students

Most of Raphael's private students and those from his studio classes were society pupils from highly respected Montreal families. One student, Wyatt Eaton (1849-1896), who had taken his first lessons from Raphael in 1866, went on to study at the National Academy of Design in New York, where he became a successful portrait painter. Another, William Townley Benson (active 1880-1906), his pupil for six years in group classes, settled in Mexico as a professional landscape artist. (A complimentary newspaper article that reviewed his art was found with Raphael's belongings). Yet another, Miss Harriet Pinkerton (1852-1936) exhibited floral studies at the Art Association. Dr. Francis Campbell, an amateur artist (active 1880-1903) sketched New Brunswick scenes "from which Raphael prepared paintings for reproduction in the Canadian Illustrated News" in 1880. From the students he taught at religious orders, Sister St-Sylvestre (1847-1927), a nun at Congrégation Notre-Dame, decorated the order's churches throughout Canada and the United States. Sister Marie Arsène (1843-1930), Head of the Art School of the Sisters of Ste-Anne, and her successor, Sister Hélène-de-la-Croix (1861-1956), both produced religious paintings and portraits and taught students who became art teachers throughout the order.

Sister Hélène-de-la-Croix wrote in her diary, «M. W. Raphael aurait pu nous donner ces leçons de dessin d'après nature… comme il ne parlait pas français.» Despite his inability to speak French, he succeeded in conveying to the students and to his star pupil, Sister Hélène-de-la-Croix, his methods of seeing and transferring nature onto canvas. Ozias Leduc commented, "the only nun in the City of Montreal that can paint is Sister Helen-of-the-Cross."

Raphael, Jacobi and Vogt

What was Raphael's relationship with the two other German-trained artists, Otto Reinhold Jacobi (1812-1901) and Adolphe Vogt (1842-1871), who were active during his career in Montreal? Raphael and Jacobi were friends in 1861, when Jacobi painted his daughter, Miss Raphael. Jacobi was also Raphael's neighbour, two doors away on German Street, from 1869-1873. Artistically, Jacobi and Vogt painted in a more romantic and idealized manner than Raphael, creating European scenes from their Canadian studios, Jacobi used photography extensively for his landscapes, into which he placed stylized figures, familiar in his gypsy encampment scenes. Vogt often filled them with animals, like another Canadian artist influenced by Jacobi - Allan Edson (1846-1888), a master in his use of light. Unlike Jacobi, there is no evidence to indicate that Raphael used photographs for his landscapes. Although there are romantic tones in some of Raphael's work, he remained true to the Biedermeier Realist tradition. He based his studies on sketches from nature, and was faithful to the Canadian landscape in all seasons and to the distinct character of its inhabitants.

As for other artists contemporary to Raphael by the 1890s, a younger group of painters, including Paul Peel and George Reid, were returning to Canada with yet more fresh ideas relating to the latest vogues in Paris. Meanwhile, Raphael's private school continued to attract students, at least until mid-decade, and he continued to teach elsewhere, well into the twentieth century.

In the last two decades before his death in 1914, Raphael, aside from teaching, painted portraits, restored paintings, and enjoyed the company of his close-knit family. He spent more time than ever on landscapes, spending long periods of time in the country. There he found great happiness, and hearkened back to the pleasurable years of his youth, when he expressed his love for nature in romantic poetry.

Content is my life in the country…

The days I spend here are so gay.

A ray of the upcoming sun

Enters my little abode.

I feel tremendously happy.

No nobleman could be happier than I in my little abode.

In retrospect, Raphael left a precious legacy. He recorded for posterity places, landscapes and faces of people of importance who contributed to Canada's growth, as well as scenes of the vanishing Indian and habitant way of life.