David Milne

"Do you like flowers? So do I, but I never paint them. I didn't even see the hepaticas. I saw, instead, an arrangement of the lines, spaces, hues, values and relations that I habitually use. That is, I saw one of my own pictures, a little different from ones done before, changed slightly, very slightly, by what I saw before me."

David Milne, 1936

"Do you like flowers? So do I, but I never paint them. I didn't even see the hepaticas. I saw, instead, an arrangement of the lines, spaces, hues, values and relations that I habitually use. That is, I saw one of my own pictures, a little different from ones done before, changed slightly, very slightly, by what I saw before me."

David Milne, 1936

Dorota Kozinska reflects on David B. Milne

Reams have been written about David B. Milne, Canada's rebel painter. There is Alan Jarvis' biography, then there is David P. Silcox's extensive treatise, Painting Place: The Life and Work of David B. Milne, then on to Reflections in a Quiet Pool: The Prints of David Milne by Rosemarie Tovell - not forgetting that Milne himself was a prolific writer who left behind a vast quantity of notes and letters. Poring over these pages - analysis and critiques, personal anecdotes and historical references, and with the excellent Catalogue Raisonnée of the Paintings Vol 1 & Vol 2, compiled by David Milne Jr. and David P. Silcox as my own Ariadne's thread guiding me through the complex tapestry of his life, I began to lose sight of the artist. The more I read, the more obscure he became. I could not forge a link with him and felt that in order to do so, I must find the thread that stitched his life and creativity together.

Milne's greatest and indisputable legacy lies in his art, and it was there that I sought the key to understanding the genius behind the gesture, embarking on a somewhat unorthodox skip-and-hop journey across Milne's unique landscape.

Like chapters in a book, his rich and prolific career is broken into distinct periods - marked by changes in personal life, and traced along a continuous, unwavering path of pictorial discovery. Both are inexorably linked, bonded for life, soldered by fate and destiny.

"He was like a piece of litmus paper," writes David Silcox. "The times imprinted themselves on him because he was original and because he was sensitive. The paintings, although they reflect the spirit of his times, also reflect him."

Milne (1882-1953) was born in rural Ontario, the sixth and youngest child, surrounded by four older brothers and a sister. The Milnes lived a frugal existence from the produce of a small market garden and a home laundry. By all accounts, Milne was drawn to art at a very early age, an interest that was later revived while he was teaching.

From correspondence studies, to a lengthy sojourn in New York, where he studied at the Art Students League, Milne's artistic path was being charted.

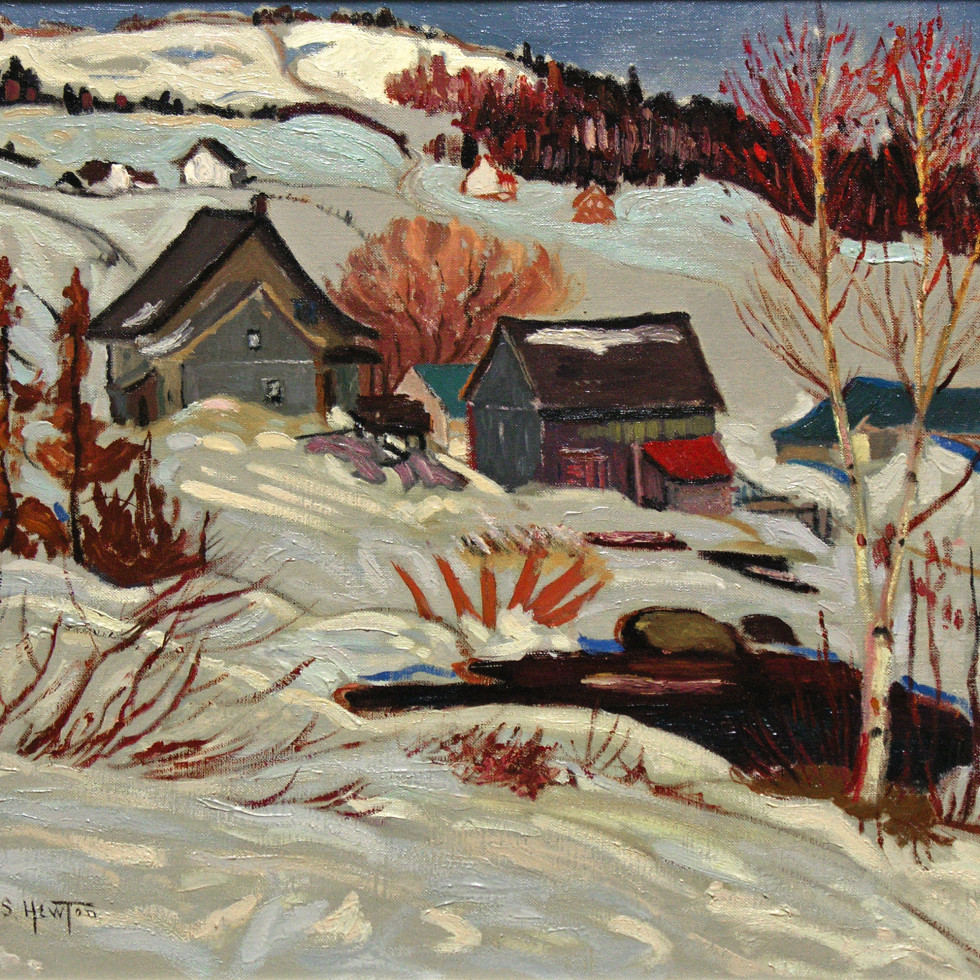

What is clear from the very beginning was his unique aesthetic and approach to painting. Milne was an exact contemporary of the Group of Seven, yet separated from them by both vision and distance. While J.E.H. MacDonald, Lawren Harris, Arthur Lismer, F.H. Varley, A.Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston and Franklin Carmichael focused on the raw beauty of the Canadian landscape, Milne spent twenty-four years living and working in the United States.

His modest by comparison works were at the time easily overshadowed by the Group of Seven's bold, monumental paintings and his reclusive nature stood in stark contrast to the Group's determined stance.

For a man "who didn't make much noise," as Robert Ayre describes him, Milne left an indelible mark on Canadian art history. In 1913, five of Milne's paintings were chosen for the famous Armory Show. Organized by the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City under the auspices of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, it included works by such great international artists as Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Derain, de Vlaminck, Kandinsky, Brancusi, Duchamp, Delacroix, Cézanne, Monet, Redon and Van Gogh. Close to thirteen hundred pieces of art were exhibited, and Milne's contributions, consisting of Little Figures, Distorted Tree, Columbus Circle (or Billboard), The Garden and Reclining Figure, were indeed in fine company.

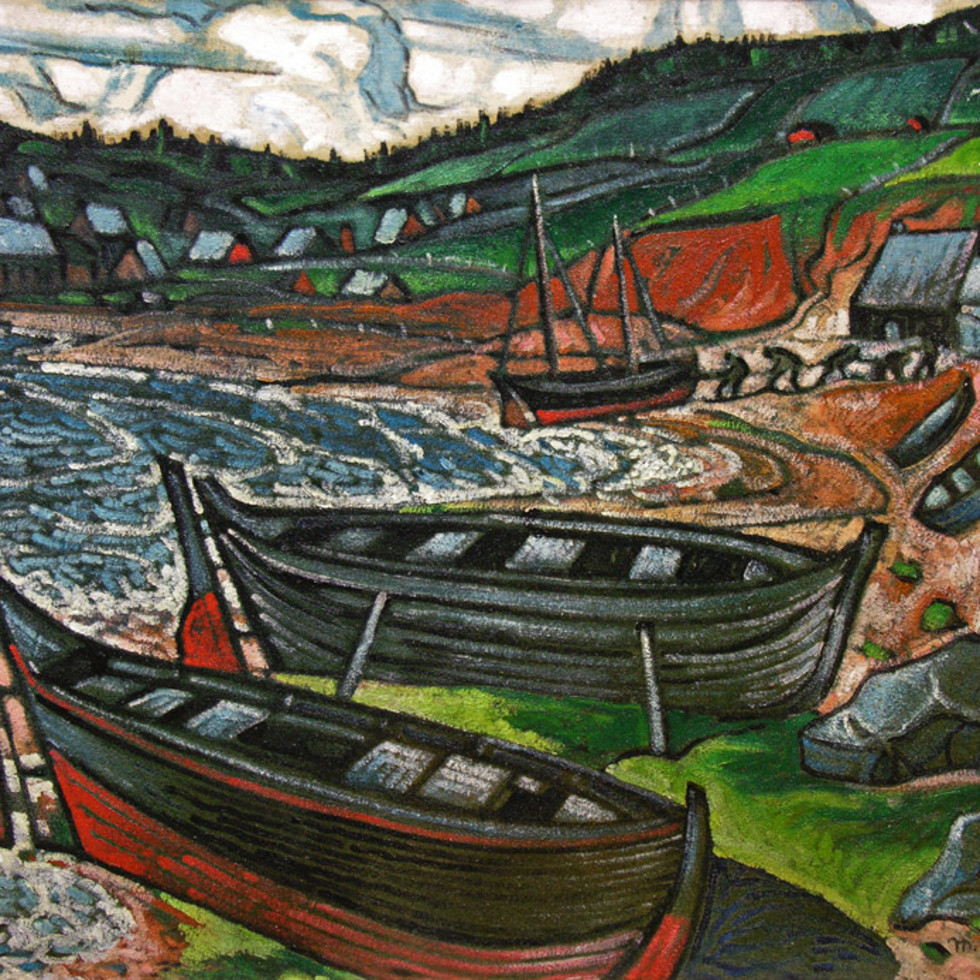

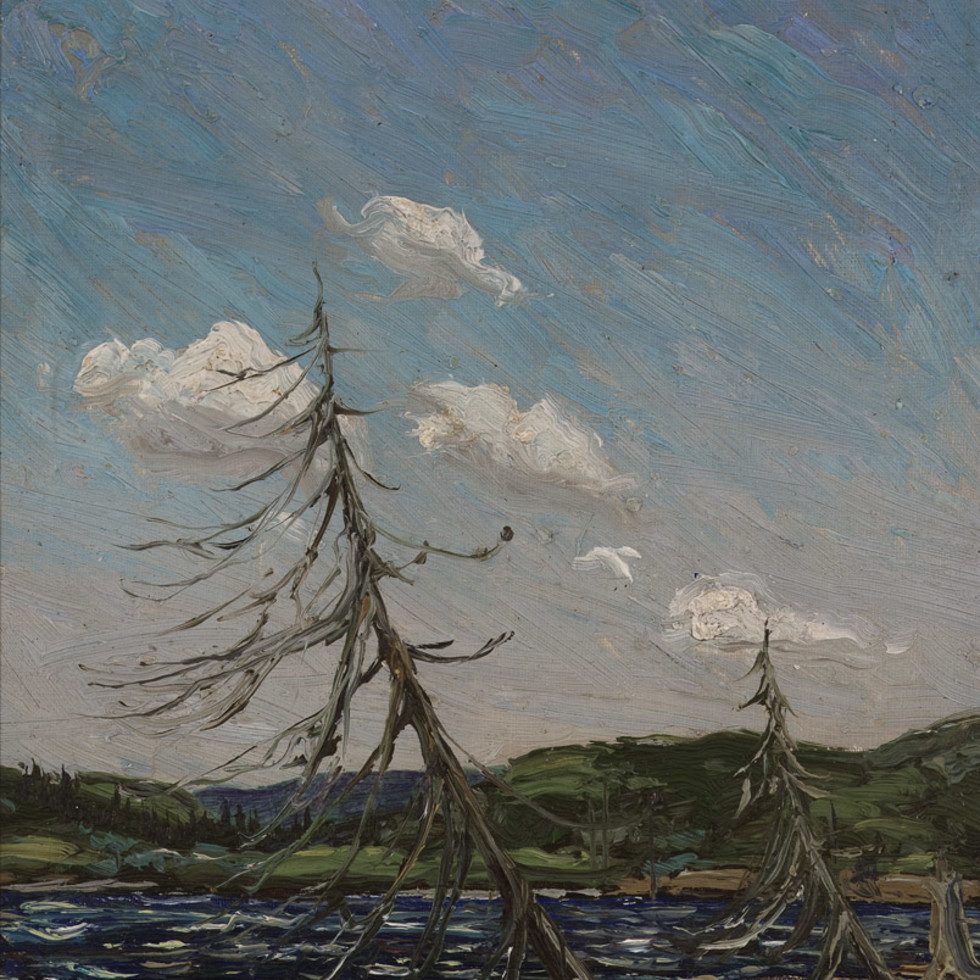

But while the international art scene was witnessing the emergence of one style after another, from Post-Impressionism to Cubism to Dada and Surrealism, Milne was quietly and persistently mapping out his own visual landscape.

If one were to seek comparison, it would have to be with the work of the Fauve painters - a motley crew of artists whose paintings confounded art critics unable to fit them into a neat category. The trend lasted a mere three years, between 1905 and 1908, and its proponents included Derain, Matisse, Dufy and Braque, artists enamoured of colour and visual exuberance.

Characterized by the abandonment of traditional pictorial approach and perspective, the use of pure colour, the modification of the relationship between painting and reality, Fauvism (from the French word Fauve, meaning 'wild beast') changed the course of art. The idea was to liberate colour and form, and in Fauvist paintings, "no point is more important than another," explained Matisse.

"To my mind," wrote Matisse, "expression dwells less in the arrangement of the subject than that of the composition of a picture, the method of placing things, the atmosphere and the empty spaces that surround them."

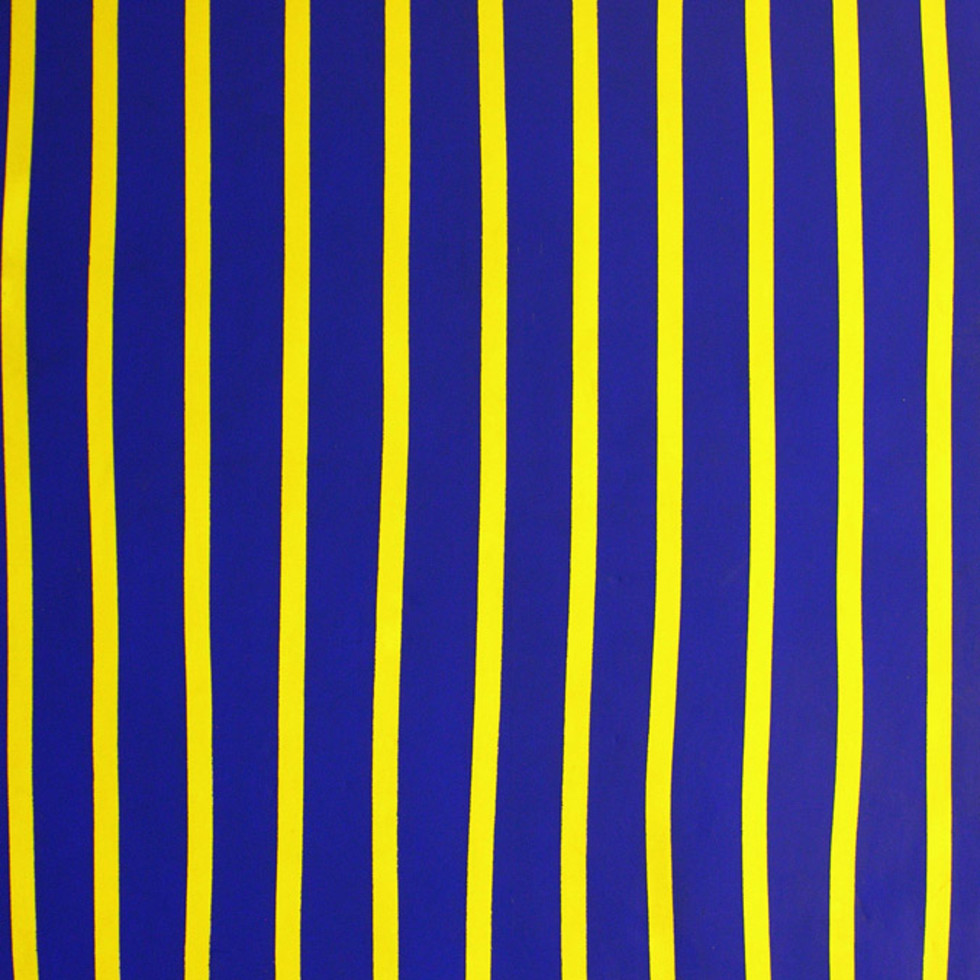

Milne's notes seem to echo these sentiments when he writes, "art has no objective, and objective is fixed, known beforehand. Art works toward the unknown. That is why it is living, not static." For him, "the art is aesthetic emotion, exhausting, to be sustained intensely only for a short time."

This intensity of emotion is precisely what links Milne with the fauvists, as does the deductive charm of his compositions.

That charm lies in Milne's economy of expression and his choice of the quotidian as subject matter. His mission was to express the most with the least, and he refined the art of reduction. His gesture was marked by a Zen-like delicacy and precision, the form hinted at in just a few lines or patches of colour. In Lady of Leisure, a watercolour painted in New York around the time of the Armory Show, Milne sketches the figure of his wife, Patsy Hegarty, by creating an outline with shimmering dots of colour, and the simplicity of it all is at once breathtaking and overwhelming.

Those were clearly happy, albeit brief, times for the artist whose life was far from easy. Money was a continuous problem, and recognition was hard to come by. Yet Milne seemed content with his modest existence, seeking solace in the rural countryside. It is as if he never really lost his roots, his vision untarnished by the swirling stream of art that swept across the western world in the first half of the last century.

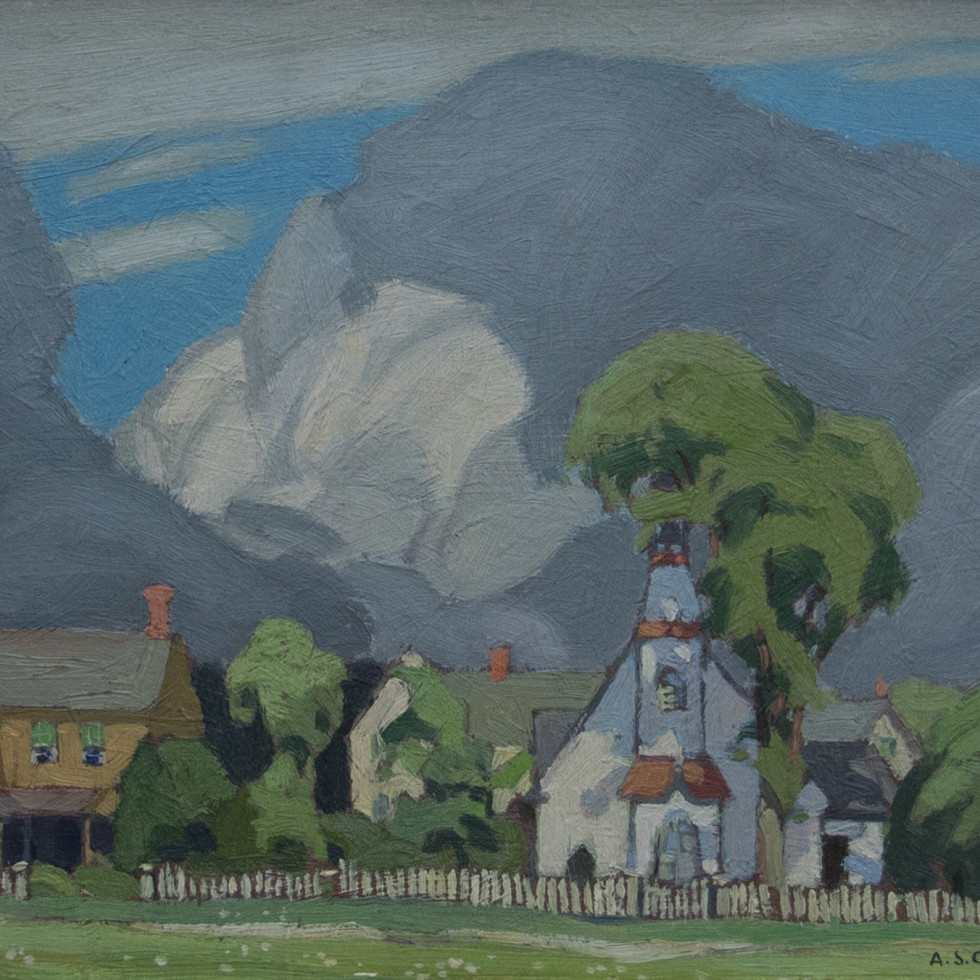

A lover of nature, like the Group of Seven, Milne was a complex mixture of visionary and pragmatist. He approached his works with an almost mathematical precision, reducing the subject to an interplay of lines and colours, contemptuous of superfluity.

He worked intuitively and passionately. "Pictures," he wrote, "are merely a by-product of the painter's effort. The important thing is the effort, the striving itself."

Yet Milne managed to imbue the simplest of subjects with lyricism, and an otherworldly sheen.

"I think we go to flowers as we go to art, because both are useless," he wrote. "Flowers and art have for us, or some of us, a complete and real existence, servants of none, aids to nothing. In our love of art and love of roses we build small heavens in our small gardens or on our thin canvases."

These small Edens were soon to give way to more somber images. By 1918 the First World War had been raging for four years, and returning to Toronto, Milne enlisted in the Canadian Army as a private. At a training camp in North Wales, he became aware of a programme of employing artists, and in 1919 he became an official war artist, (as did several other Canadian painters including Varley, Jackson and Maurice Cullen to name but a few).

Milne's output during his time with the army was particularly prolific. After completing thirty-seven paintings in various camps in England, he headed for the Vimy-Arras area in France, where he remained until the end of July 1919. Next he painted in the Ypres-Passchendaele area, and the Somme. Close to seventy paintings mark that period.

Done mostly in drybrush watercolour, a technique he mastered to perfection, they reveal the aftermath of war, but unlike Varley's emotionally charged scenes of devastation, Milne's images are devoid of drama and horror. Stylized and elegant, they are a personal vision, staunchly consistent with his style.

Describing his work titled, Bramshott: The London-Portsmouth Road, painted in England in 1919, Milne reduces the image to an interplay of contrasting tones: "I am doing one of the Portsmouth Road, looking against the light where the range between the shadowed and lighted forms calls for the limit - black and white," he wrote in a letter. "I am going to distinguish my black forms from one another by broken edgings of brilliant color - imperfect halos - the Khaki black, with yellow trimmings - Hospital Blues, black with bright blue - Black Watch kilt, black with glue-green - 48th kilt... black with brick-red edging."

This somewhat cold reduction of a poignant scene to a pictorial mosaic does not brand Milne as heartless. It only makes him more human, wrestling like many before him, with the creative vision through which everything else is filtered. It made me think of Monet at his wife's deathbed, tormented by anguish and the overwhelming need to translate the image before him into a canvas of light and darkness, seduced by the shadows slowly transforming the map of her face.

One must not forget that Milne was a quiet, thinking man, not prone to outbursts. His paintings were quiet, too, and at times achingly lyrical. "Feeling is the power that drives art," he once said, and his works testify to his unique sensibility.

There is something Oriental in Milne's style, characterized by delicacy and elegance, a simplicity that can only stem from a profound introspection.

He spent years living alone in a secluded cabin, which he built himself, sustained, as it were, by art.

There is no doubt that Milne's dedication to his craft had its effect on his personal life. Criticized by some as a megalomaniac to whom painting was the only thing that mattered, he may have been guilty as charged, but for an art critic, all that is really important is the art, and with a legacy the size of Milne's, that is all that should matter.

To understand just how important painting was to Milne, one only has to look at the decades of physical hardship he endured in order to pursue his goal, and, ultimately, he sacrificed his marriage in the name of art.

Milne went through periods of great privation, never losing sight of his vision, never succumbing to despair. He painted relentlessly till the very end, the fluctuating tones of his paintings echoing his inner torment. Living in Uxbridge, where he settled in 1940, with illness and financial woes as backdrops, Milne paints a nocturnal series (Scaffolding) marked by an ominous, dark palette and a ghostly, shimmering façade of a building. The effect of these works is striking, achieved, as usual, with an astounding economy of means.

Light returns to Milne's canvas towards the end of his life. Lighted Streets, painted in 1951, is in stark contrast to the Scaffolding paintings. Done from a drawing he sketched while in hospital, it's a shimmering tableau of esoteric proportions.

The light becomes even more ethereal in the Storm over the Islands series, rendered with gentleness and emotion. These works are like illustrations to Oriental haiku poems, imbued with a touching sensitivity.

"Art is not an imitation of anything or a daydream or a memory or a vision," Milne wrote. "It has an existence of its own, an emotion we cannot get from anything in life outside it."

Milne was unquestionably one of Canada's most talented and original artists. He was a loner, like Emily Carr, dancing to his own tune, eschewing any and all trends in order to create his own unique style and philosophy of painting.

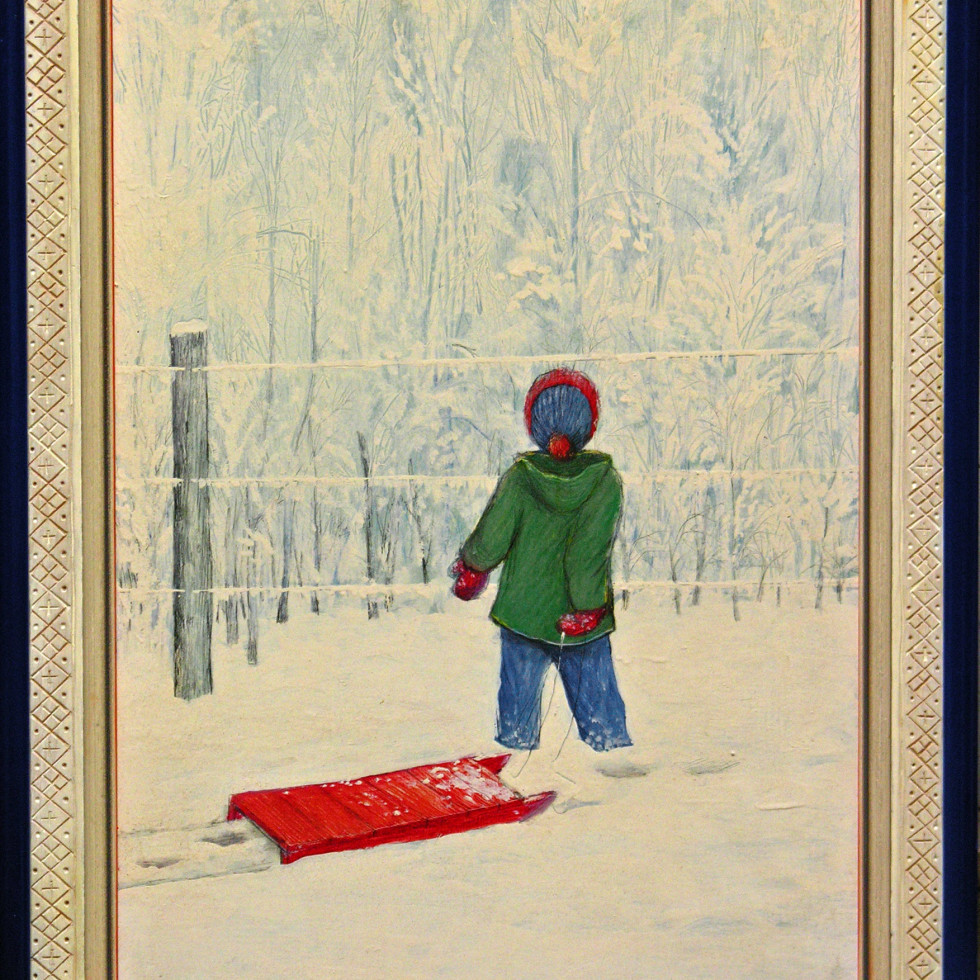

Enamoured of both intimate, unpretentious interior scenes and vast landscapes, he occupies a special place in the annals of Canadian history.

Source: David Milne Retrospective Exhibition Catalogue, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff (2001). Text by Dorota Kozinska.

© Copyright Dorota Kozinska and Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc.

David Milne Exhibitions at Klinkhoff

DAVID MILNE

28th Annual Retrospective Exhibition

September 15 - 29, 2001