Ethel Seath

"The aims of Art education are to help children to see, to feel and to express beauty with clean, spontaneous feeling. It should given them the ability to use the experience of everyday life creatively, in order that they may gain increased intelligence through the use of their hands . . . Nearly all children have something to say through drawing, and training in Art results in refinement of thought, eye and hand."

Ethel Seath

"The aims of Art education are to help children to see, to feel and to express beauty with clean, spontaneous feeling. It should given them the ability to use the experience of everyday life creatively, in order that they may gain increased intelligence through the use of their hands . . . Nearly all children have something to say through drawing, and training in Art results in refinement of thought, eye and hand."

Ethel Seath

By Roger Little

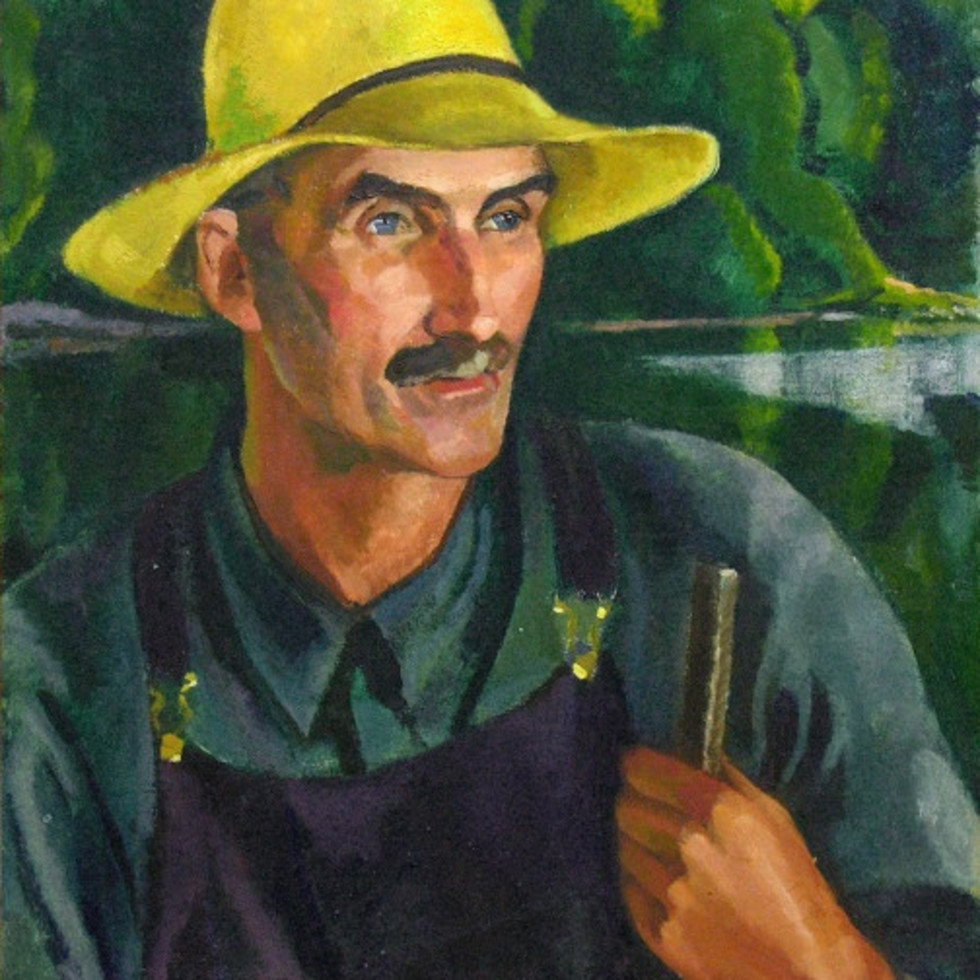

For over sixty years, Ethel Seath was a familiar figure in the Montreal art scene. Selfless, earnest, and sincere, she was a pioneer among the artistic women of her generation. She implicitly challenged the conventions of Victorian propriety with a soft-spoken but resilient independence. At the Art Association of Montreal, she had studied under William Brymner, Edmond Dyonnet and Maurice Cullen, later reflecting their example of a native and forward-looking art. Following a career of two decades as a commercial illustrator, she found her métier as an inspired art teacher at The Study School. As a founding member of the Beaver Hall Hill Group and of the Canadian Group of Painters, Ethel Seath contributed to exhibitions at home and abroad.

In this retrospective exhibition [this text was written for the Ethel Seath Retrospective Exhibition, in 1987 - ed.] at Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, fifty works have been assembled in the first comprehensive review of Miss Seath's career. These paintings include still-life and landscape compositions in oil and watercolour. The untroubled lyricism of her art is an intimate exploration in colour and design. This collection is a sensitive and charming testament of one woman's creative impulse and vision.

On June 29, 1903, The Art Association of Montreal published a register of local artists, in which Ethel Seath is described as the youngest artist working in black and white in Canada and as having already been engaged in newspaper illustration for some years. The reference is little more than a passing glimpse, but before closing and moving on to the next subject, the editor allows himself a prophecy: "Although Miss Seath has seen little of the world as yet, with further opportunities for study and acquaintance with the masters of art, much may be expected of her." In the quaint photograph which accompanies this profile, an alert face, with a steady gaze and a sensible little mouth, peers out from under a pile of "Gibson-girl" hair. The bodice is covered with a patchwork of soft cotton lace. Miss Seath was all of twenty-four years old.

For many of those today who knew Ethel Seath or have learned something of her through the infectious bonhomie of her art, this "portrait of the artist" will seem impossibly young. As a perennial figure for decades in the Montreal art milieu, a more mature and stolid image may readily come to mind. The same expression undoubtedly peers out, but now a lace patchwork appears only in the lines of a gently aging face, while a functional tweed suit replaces the Edwardian tea gown. As for the expectations of renown, these may probably have embarrassed no one more that the subject herself. Ethel Seath had little taste for worldly fame or attainments - discreet, self-effacing, reserved in manner, she gladly eluded the glare of the spotlight the whole of her long and productive life. Her simplicity and lack of affectation were easily her most endearing virtues. She was content to speak with a quiet voice among the extended fraternity of her art. The companionship of close friends and the appreciation of her students was the true source of her peace and fulfillment. Her art is the reflection of a gentle nature.

Ethel Seath was born in Montreal on February 5, 1879, into a family of Scottish-Presbyterian descent. Her father, Norman Seath, suffered from chronic ill-health and, in time, it was necessary for the Seaths to economize and for the children to help make ends meet. Ethel was the second of five children and the eldest of three daughters; understandably, she and her older brother felt their responsibility the most keenly. For Ethel, this meant finding work as soon as her schooling was finished. Although fun-loving, she was nonetheless a serious person and however much those early years may have necessitated her maturing more quickly than others her age, Ethel was equal to the challenge.

As she faced the world, she could not have taken long to brood over the problem of employment - the choices were focused by a natural talent. Since childhood, an attraction to drawing had become a passion. One suspects that Ethel must have fondly remembered her youthful view of the world. The inspired primitivism of a child's uncorrupted vision is a quality she would never herself lose and which she would later encourage and cultivate in her students.

When a position became available at The Montreal Witness in 1896, it gave Ethel the chance to continue drawing. She was only seventeen years old. The well-known cartoonist, Arthur G. Racey, was at that time head of the art department. Ethel later recalled "that, for a wide-eyed, inexperienced girl, his encouragement and guidance had been extremely valuable."

By October of 1901, having moved to the art staff of The Montreal Star, Ethel found another sympathetic influence in Henri Julien, the dean of Canadian illustrators and a renowned figure. Within two years, an Art Association Newsletter could report: "Her work rapidly improved, and her original illustrations have become a regular feature of the Weekly Star." Ethel had found her footing, gaining confidence and skill in her chosen profession. She might well have felt pleased with herself. The future looked assured.

It was remarkable in a young life, already crowded with the demands of her profession that Ethel was able to find time to paint. During those years, throughout the 1890s into the 1900s, commercial drawing helped pay for her classes at the Art Association of Montreal. There, as with so many of her generation, William Brymner's subtle use of light and colour helped shape Ethel's own interests. Later, after 1911, when Maurice Cullen took over the sketching course from Dyonnet, she joined a few of his lively forays into the Quebec countryside.

In a catalogue of works exhibited in 1903, when Ethel was twenty-four, her titles suggest an attraction to nature as well as to homespun domesticity. She was still working in black and white and the subjects were carefully rendered. In those formative years, pen and paper were her natural media, just as representational nuance was her stock-in-trade. It is likely that Ethel's early mastery of these skills served to spark all the more her imaginative response to the possibilities of painting. When her oils began to appear in the annual spring exhibitions of the Art Association, they showed signs of new form. The subjects were still anecdotal glimpses of city and country life, but the colour and line revealed an awakening sensibility. The curvilinear patterns which would often characterize Ethel's work, the bold colours and the occasionally abstracted naivety of her eye - all were evidence of a tenacious if quiet independence. Painting for Ethel almost certainly became a relief from the technical requirements of newspaper illustration, as well as from the rigid expectations which prevailed for young women in the late Victorian period. In this sense, painting would be Ethel's, "flight of fancy," her "sesame" to the imagination. During the various phases of her career, art was the affirmation of a contented and creative spirit.

When she had been a commercial artist, Ethel could enjoy the autonomy of her own career. It had given her private status and self-confidence. It also gave her self-knowledge and the awareness that the increasing demands on her time inevitably hindered freedom to paint. After twenty years as an illustrator, and now thirty-eight, Ethel courageously embraced the opportunity of a new life. In 1917, Margaret Gascoigne, having just found The Study School in Montreal, invited Miss Seath to become their first art teacher. For the next forty-five years, The Study would know no other. Ethel later recalled, "I thought no more of teaching than of flying until I met a fine person who was starting a school… Miss Gascoigne had seen one of my 'little things' in the museum and asked me to join her." Their meeting was one of kindred spirits. Ethel left the Family Herald, where she had been latterly employed, and never looked back. She may well have felt that, having met the challenges of being a newspaper woman, her experiences and lessons had been digested and she could now move on. She would certainly learn that teaching art posed a stimulating problem in its aesthetic sense, a stimulant lacking in the more empirical objectives of commercial life. Above all, Ethel would find The Study a place where she could paint and talk about painting. Not particularly competitive or at all aggressive, her nature responded to understanding and friendship in a secure environment. The Study supplied her with a second family, and one in which her role could be meaningful.

In the fall of 1920, Ethel joined an intimate coterie of Montrealers in forming the Beaver Hall Hill Group. Their concept of art was similar to that of the nationalist school, championed and led by the Group of Seven, which also came together in 1920. Although it would survive only a few years, the Beaver Hall Hill Group produced a distinctive and independent vision. All of its members had studied together under Brymner at the Art Association of Montreal. The group included Edwin Holgate, Randolph Hewton, A.Y. Jackson, Adrien Hébert, Robert Pilot, and André Biéler, but it was the women in particular who gave the group its characteristic flavour. In this loosely formed association of artists, Ethel Seath was in company with such old friends as Sarah Robertson, Prudence Heward, Kathleen Morris, Lilias Torrance Newton, Nora Collyer, and Anne Savage. Their social and emotional homogeneity was remarkable. As Norah McCullough has suggested, many of these artists were "by no means careerists, but rather talented gentlefolk… woman of superior intelligence and rigorous energy." This remark suggests the appealing integrity of Ethel Seath and the Beaver Hall ladies, for although they were "gentlewomen," there was nothing tepid in their discipline to paint. In her biography of Anne Savage, Anne McDougall writes: "In an era where proper young ladies were expected to pick up an embroidery needle before a paint brush (and neither on Sundays), these painters were never amateurish."

Rich in their individual yet comparable styles, it might almost seem as if these ladies had founded a school unto themselves. Anne McDougall describes their effect:

"If you put their painting all together, you get a 'Montreal look'. It is a look of colour and mood; much of it comes from the French details: outside staircases, wide balconies, nuns strolling in convent gardens… It is a look quite different from anything else painted in Canada."

In her career as an art teacher, Ethel enjoyed success from the beginning. In Four Decades, Paul Duval writes that she brought "imagination and freedom to an art curriculum still corseted by rigid Victorian discipline." Her attitude towards art as a liberating sensibility coincided with the revolution in education taking place at that time. Children were now to be given the chance to learn through the development of discovery and not by the imposition of more repetition or dictated moral precepts.

Ethel outlined her views in 1935:

"The aims of Art education are to help children to see, to feel and to express beauty with clean, spontaneous feeling. It should given them the ability to use the experience of everyday life creatively, in order that they may gain increased intelligence through the use of their hands […] Nearly all children have something to say through drawing, and training in Art results in refinement of thought, eye and hand."

The children only knew that they love it all, and have never forgotten the teacher. For many of her students, The Study of their youth was the old red brick building on Seaforth Avenue and the large airy art room on the top floor of the Junior House. The atmosphere was more like that of a family than a school. Today, many recall the art room as a place of magic and serenity. With large sheets of white poster paper and jam jars full of paint, Ethel would set her charges free. "Don't be shy," she would say, "fill the page, make a mess!" Ethel wanted action and motion in her students' work. She transmitted to them the adventure of what they might see and feel. She once said, "one can teach how to merely paint or draw, but one can't be taught to put an individual's spirit into a picture, that comes from deep within."

Ethel's teaching bore fruit in heady triumphs for her students. In the 1930s, selections of their work were sent to children's art exhibitions in South Africa, across Canada with the National Gallery, as well as in a tour of the United States.

The 1930s and '40s were Ethel's peak years as both a teacher and artist. The rewards of the classroom were matched by a sustained activity at the easel. The opportunities in which she could find time to paint were still precious to her, but her life had become busy. In 1937, she had started teaching the Saturday morning classes at the Museum. In addition, her mother's failing health demanded more of her attention.

The Contemporary Arts Society elected Ethel a member in 1939, as did the Federation of Canadian Artists. That was still a period in which a general lack of galleries prevented artists from easily exhibiting their work. The coordinated efforts of painters in pooling resources, particularly during the depression years, was a necessity for both their social and artistic life. The Contemporary Arts Society, founded in 1939, professed the ideal of a "living art", putting emphasis on "imagination, intuition, and spontaneity, as opposed to conventional proficiency." In a circle of artists, comprised mostly of Montrealers, Ethel's appeal was understandable. The example of her work was one of joy and creativity - the expression of a pure soul without malice or cynicism. This quality of innocence endeared Ethel to her colleagues, while her innovation as an educator won their respect.

In the mature years of Ethel's life, her art - and that of the other Montrealers with whom she has been associated - has been described as a swan song to a vanishing way of life. Although she would often experiment with different styles and moods, the painting of these years constitutes possibly Ethel's best work. The landscape scenes in particular take on the poignancy of Quebec's rustic and by-gone days.

Ethel joined the Canadian Group of Painters in 1940 and, under its auspices, contributed for much of the rest of her life to exhibitions at home and abroad. In 1939, her work Studio Table was included with the collection of works by Canadian women painters at the New York City World's Fair. In 1924, Ethel had been represented at The British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. In 1951, her canvas of a white barn in the Townships at harvest time was selected from the National Gallery collection to hang with twenty Canadian paintings at the Festival of Britain.

Ethel frequently painted with friends during the happy breaks of holiday excursions. Indeed, these were often the only occasions when she could work free of care and interruption. The usual summer visits to the Lower St. Lawrence region - where Ethel found the inspiration for so many subjects - were occasionally varied. In 1948, she was in Nova Scotia with Nora Collyer and Sarah Robertson where they showed their recent work of intimate harbour scenes and ocean-hugged coastlines. In the same year, Ethel exhibited in Windsor, Ontario at the Willistead Art Gallery in conjunction with Anne Savage and Prudence Heward.

Her Montreal shows, in the middle to late 1950s, delighted the public and critics alike. At The New Gallery XII in July of 1962, Ethel Seath stood in the shadows to shyly introduce her latest work. It would be her last exhibition. A year before she died, the review in The Montreal Star unwittingly spoke her eulogy as an artist:

"Miss Seath's first concern is with colour and design. She gets them both from the earth and the fruits of the earth. She can be vigorous as well as felicitous but she is never violent; while she may paint a waterfall, she puts it in its place behind a frame of branches, and ornamented with leaves and berries, a pattern of field flowers… But while she clings to the objects she knows and loves, she has a strong sense of their abstract qualities."

Ethel Seath had a capacity for growth and discovery as fresh and unspoiled as that of any of her students. On her retirement from The Study in the fall of 1962, and at eighty-three years of age, Ethel confessed her new interest to "do abstracts." She had often told her students, "don't slam it! You may grow into it." Ethel had already begun to act on her own advice, when, in failing health, she died in the spring of 1963. The announcement of her death in local newspapers recorded her services to education and art. Not one of these was more poignantly appropriate than the few well-chosen remarks, which appeared in The Study Chronicle:

"Ethel Seath died on April 10th, 1963, after a lifetime dedicated to her chosen profession. One of Canada's finest painters, Miss Seath devoted herself to teaching and was never interested in personal fame or recognition. In spite of herself, and of those wonderful qualities of humility and selflessness, she has left behind her a treasury of paintings which are a lasting memorial to her life as an artist.

Miss Seath had two families, her own small circle of relations, and her widespread and beloved family of Study Girls, their daughters, and granddaughters. Her gentle influence on hundreds of lives… is perhaps her greatest memorial of all."

© Copyright Roger Little and Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc.

Ethel Seath Exhibitions at Klinkhoff

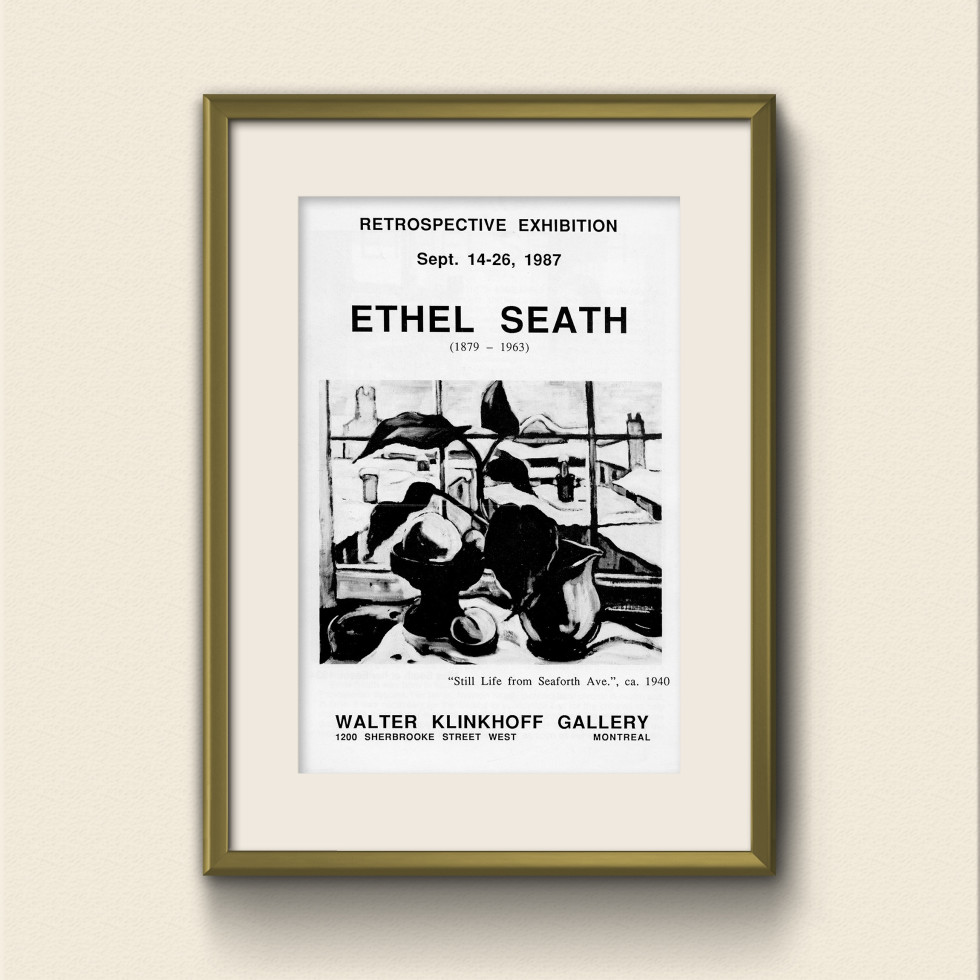

ETHEL SEATH

14th Annual Retrospective Exhibition

September 14 - 26, 1987

BEAVER HALL HILL GROUP

26th Annual Retrospective Exhibition, 1999

BEAVER HALL GROUP

Exhibition for the Auxiliary of the Montreal Chest Institute

April 25 - 28, 2007