Prudence Heward

"I think that of all the arts in Canada painting shows more vitality and has a stronger Canadian feeling... there is more interest shown in figure painting than previously and I hope we shall develop something interesting and Canadian in feeling, yet universal, modern, yet timeless."

Prudence Heward, circa 1942

"I think that of all the arts in Canada painting shows more vitality and has a stronger Canadian feeling... there is more interest shown in figure painting than previously and I hope we shall develop something interesting and Canadian in feeling, yet universal, modern, yet timeless."

Prudence Heward, circa 1942

by Janet Braide

Prudence Heward and her contemporaries began to paint when the international world of art was in ferment. In the 1920s it was possible to observe and absorb a great variety of artistic styles. Young Canadian artists were eagerly analyzing the work of the moderns and struggling to free themselves from academic rigidity. Some of them were more successful than others, particularly since it was for many of them a process which demanded hard thinking as well as painterly skill. Heward's study and investigations resulted in early works of promise, consistent quality throughout her career and, in her last works, great vitality and skilled resolutions of the painterly problems she had set for herself from the start.

Born in 1896, Efa Prudence Heward was never physically strong and she died in her fifty-second year. As a result she left fewer paintings than most of her contemporaries who continued to work for twenty-five years or more after her death. A.Y. Jackson, a life-long friend, wrote in the catalogue introduction for her Memorial Exhibition of 1948:

"She did not find it easy to paint... Her usual procedure was to use one of her landscape sketches as a background for a figure piece. She liked working on large canvases and she would struggle with many misgivings for fullness of form and bold contrasts of colour."

Heward found it easier to paint small works and a fellow artist who sketched with her envies the deft way in which she executed them. She made a quick outline, laid down the colour and was finished almost before the other woman had started. For her larger works, surviving pencil studies suggest that she used the traditional method: quick study sketches on paper, oil on panels (usually 12 x 14 inches in size) and finished works in oil on canvas.

Heward took her first drawing lessons in 1908 when she was only twelve years old. In 1918, she entered the school of the Art Association of Montreal (now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts). There she pursued the same rigorous French academic course provided by the school since the days of Robert Harris.

Starting with drawings of plaster casts of parts of the body, drawings Heward liked to bring home to show her family, she moved on to study and draw from living models. When she was ready to paint in oil, she worked first with William Brymner and then with Randolph Hewton. She exhibited a small sketch at the Art Association's 37th Spring Exhibition in 1920 and in 1922, contributed a portrait, Mrs. Hope Scott, to the 39th. That year Heward won the Reford second prize for drawing. In 1924, she won the Reford prize for painting and the Women's Art Scholarship. With the assistance of this scholarship and the enthusiastic support of her family, Heward was on her way to France in 1925.

Her period of study in France was relatively brief, but its impact is clear since some aspects of painting styles of the loosely associated group now called The School of Paris are reflected in all her subsequent work. These influences together with her precise academic training at the Art Association in Montreal formed the basis for what over the years was to develop into a distinct personal style.

Heward started to work on large canvases as early as 1927, and eight sizable works painted between that year and 1933 show her awareness of current international styles. In Girl on a Hill, 1927, NGC, and Anna, ca. 1927, NGC, Heward places her figures in a studio landscape using the forms of Art Nouveau. The Emigrants, 1928 and At the Café, ca. 1929, MMFA, include some of the hard lines of Art Déco. The open work on the back of the dress of one of the models in At the Theatre, 1928, MMFA, has a Matisse-like flat decorative design. Rollande, 1929, NGC, is filled with the shapes of Cézanne. In The Bather, 1933, AGW, Heward attempts natural abstraction.

While experimenting with style, she was struggling to achieve her own expression and individuality. For example, Heward's figures are carefully outlined. She was a fine draughtswoman and used a neo-classical technique during the first half of her career. She does not model with soft chiaroscuro but uses darks and lights to create strong, sometimes harsh, planes in fabrics and flesh. She reduces her subjects to relatively simple shapes, then reconstructs them on the surface of the canvas. Her figures are statuesque, indeed some are monumental, in a manner that is enhanced by their position in relation to the picture plane.

During her first lessons at the Art Association she drew simple shapes. Thus her eye was trained to see that way and she was to become very specific about shapes and colours. When she looked at an object she commented about its colour first, always using explicit painters words to describe what she saw. In most of these eight early large works it is the contrapuntal play of colour across the canvas that relieves the monumentality of the figures. Her palette was one to which she would return again and again: pink, green, lavender, blue and brown. In her last works, using the same colours, she increased their values to a fauve intensity for a still life, or muted them to create a mood around a seated figure.

Figures dominated her early works, but they were supported by backgrounds derived from her little sketches. The studio landscapes and stylized vegetation inform us about the sitter, complete the composition structurally and provide a vehicle for Heward's technique of playing her colours back and forth across the canvas.

Girl on a Hill was included in an Exhibition of Contemporary Painting at the Art Association of Montreal in 1928. In 1929, despite its flat decorative quality and dark unexplored colour, it won the Willingdon Art Competition first prize. This was a triumph for an "unknown" artist. Dennis Reid wrote in his book A Concise History of Canadian Painting:

"Girl on a Hill displays more than a passing acquaintance with the subtle colours and classical compositions so dear to Parisian taste during the early years of the century."

This work and Anna are the result of her first visit to France where she had enrolled in Académie Colarossi, working in painting with Charles Guérin who had been a pupil of Gustave Moreau, the teacher of Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, and in drawing with Bernard Naudin, an illustrator, who had been a pupil of Léon Bonnat at the École des beaux-arts.

It was during this visit to Paris that, at A.Y. Jackson's suggestion, Heward arranged to meet his young Toronto friend, Isabel McLaughlin. They had tea together, with Lucile and Clarence Gagnon, and became lifelong friends. They returned together to Europe and painted in the Scandinavian Academy and sketched at Cagnes, in the southeast corner of France. Heward later traveled on to Italy and from this visit resulted small J.W. Morrice-like sketches of Florence and Venice.

After Heward's second visit to Europe there was "a severe hardening of her style," to quote Charles Hill, writing in the catalogue for the National Gallery of Canada Exhibition, Canadian Painting in the Thirties. Hill cites Sisters of Rural Quebec, 1930, AGW, and Girl Under a Tree, 1931, AGH, as examples of this change. Girl Under a Tree was called "Bougereau nude against Cézanne background" by Heward's contemporary, John Lyman. Certainly his statement gets to the heart of the matter. However Heward made a strong attempt to relate the hiss shapes and plant forms to the contours of the woman's body. The careful construction of her figure is reflected philosophically, if not in fact, in the Cézanne-like architectural grouping on the horizon. The work cannot be quickly dismissed. But Lyman was very critical:

"[It is] disconcerting to find with extreme analytical modulation of figures, [an] unmodulated and cloisonné treatment of [the] background without interrelation."

In reporting Lyman's critique, Charles Hill adds, however, that the work "has a compelling quality... an aura of high-strung sexuality."

Certainly it was a courageous undertaking for a woman painting in Canada in 1931. It is, in fact, a mélange of styles - Henri Rousseau, Paul Cézanne, Edouard Manet, Alphonse Bougereau - and the result is somewhat surrealistic. It must have excited much comment when it was exhibited in a Group of Seven show at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the AGO) in 1931.

Prudence Heward was preparing at this time for a solo exhibition to be held at W. Scott and Sons in their Montreal Drummond Street Gallery. Included were some of the paintings discussed above, together with landscapes and portraits of members of her family - in fact a full collection of her work at the time. The critic for The Montreal Gazette wrote in April of 1932 that her work was marked by "brilliant color, strong modeling and interesting rhythmic composition... In her portraits... the background is always an integral part of the picture... Her canvases are pervaded with unity of form, feeling, color and theme... [In] Girl Under a Tree... the deep flesh tones form an effective contrast to the rich blues, greens and purples of the exotic stylized landscape."

A.Y. Jackson wrote for the Montreal Star:

"Whether one styles her work as modern or not is of little moment - it is characterized by draughtsmanship of a high order, with spaces generously filled. In some case I would find the modeling of the figures too insistent - one becomes too conscious of the artist's understanding of planes and would feel happier if more was left to the imagination."

Heward considered herself a "modern" and this is evident in the associations she joined and the friendships she made. In 1921, together with other Brymner pupils, she organized the loosely associated and short-lived Beaver Hall Group. In 1933 she was an original member of the Canadian Group of Painters, an outgrowth of the Toronto-based Group of Seven. She was the vice-president of this organization for five years and when some of the Toronto members (notably Will Ogilvie and Lawren Harris) had occasion to visit Montreal they stayed in her mother's Peel Street home. In 1939 she was a founding member of the Contemporary Arts Society together with John Lyman, Jori Smith, Paul-Émile Borduas, Allan Harris and others who considered themselves to be the avant-garde in Montreal.

Despite her apparent gregariousness, Heward was in fact a quiet and thoughtful woman who made her Peel Street studio and her work the centre of her life. Here her dear friends gathered. Numbered among the closest of that group were Sarah Robertson, with whom she had studied at the Art Association; Kathleen Morris, whose family had known the Hewards since both the artists were little girls; A.Y. Jackson, Lawren Harris and Isabel McLaughlin, her friends from Toronto; and André Biéler and Gordon Webber.

On occasion her painter friends took up the pen and Arthur Lismer wrote the following in May of 1934:

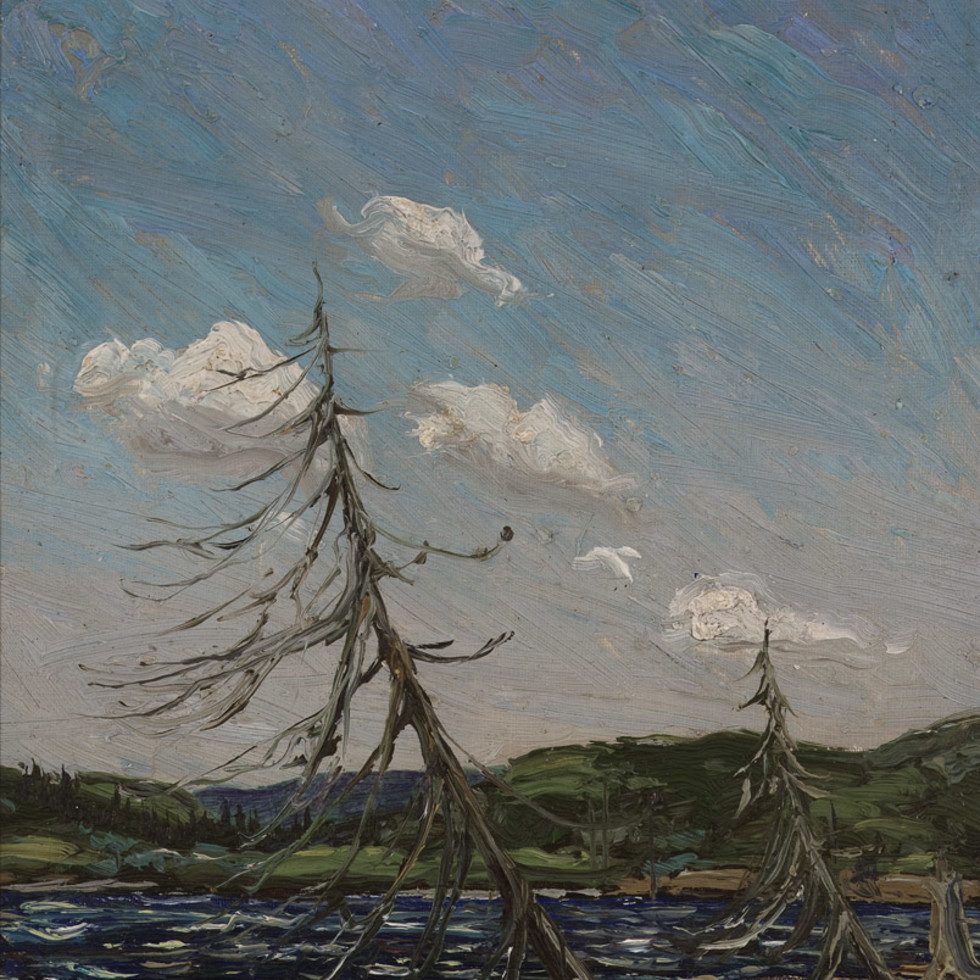

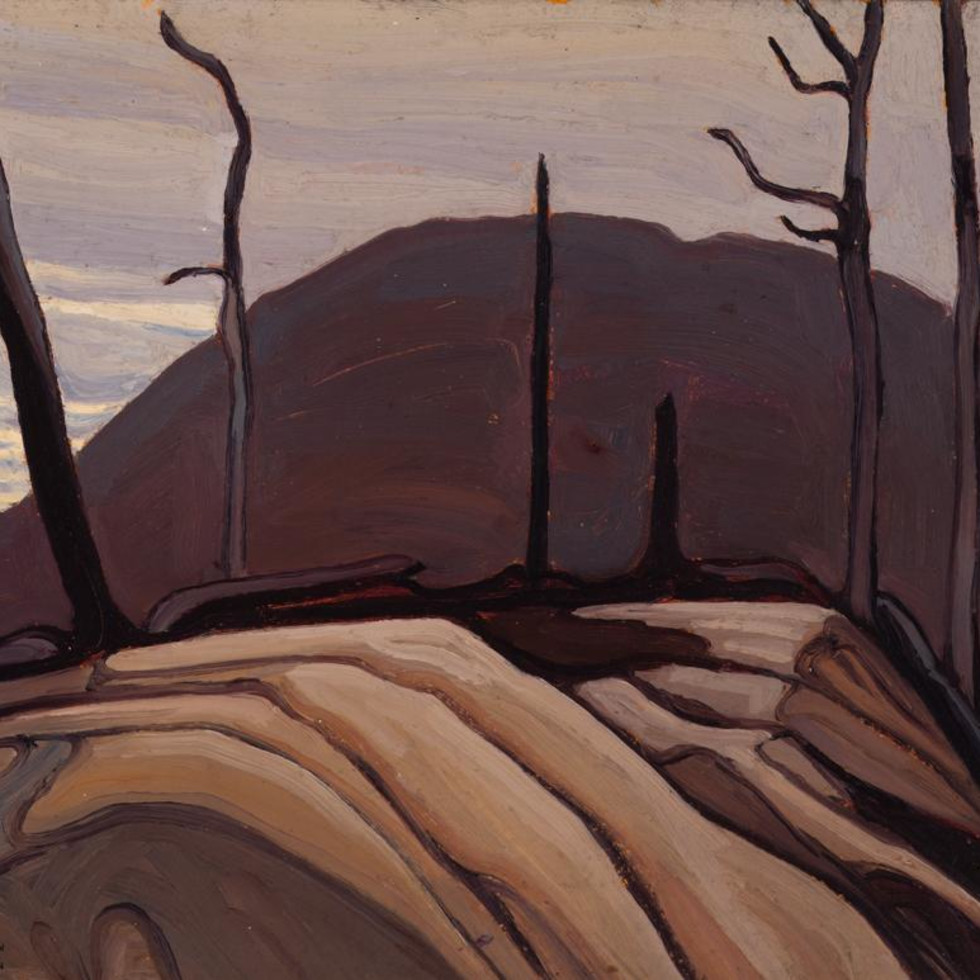

"[Heward's] landscapes avoid anything in the way of pretty textures or pictorial detail. They are concerned more with the structure and movement of the earth and tree forms than with the likeness of the scene."

The landscapes to which Lismer referred may have been Shawbridge, Piedmont and September painted when Heward, Robertson and McLaughlin had a car and they toured the countryside.

Robert Ayre wrote about two of these works in The Montreal Gazette of April 1935:

"The great solid body of the earth goes rolling through Prudence Heward's Shawbridge and her Piedmont picture is a rich pattern of hillfolds, colored trees and water. Never content with mere surface impressions Miss Heward is a painter of profound integrity, a painter who both stimulates and satisfies."

This was encouraging praise from a writer who would prove to be one of Canada's most sensitive art critics.

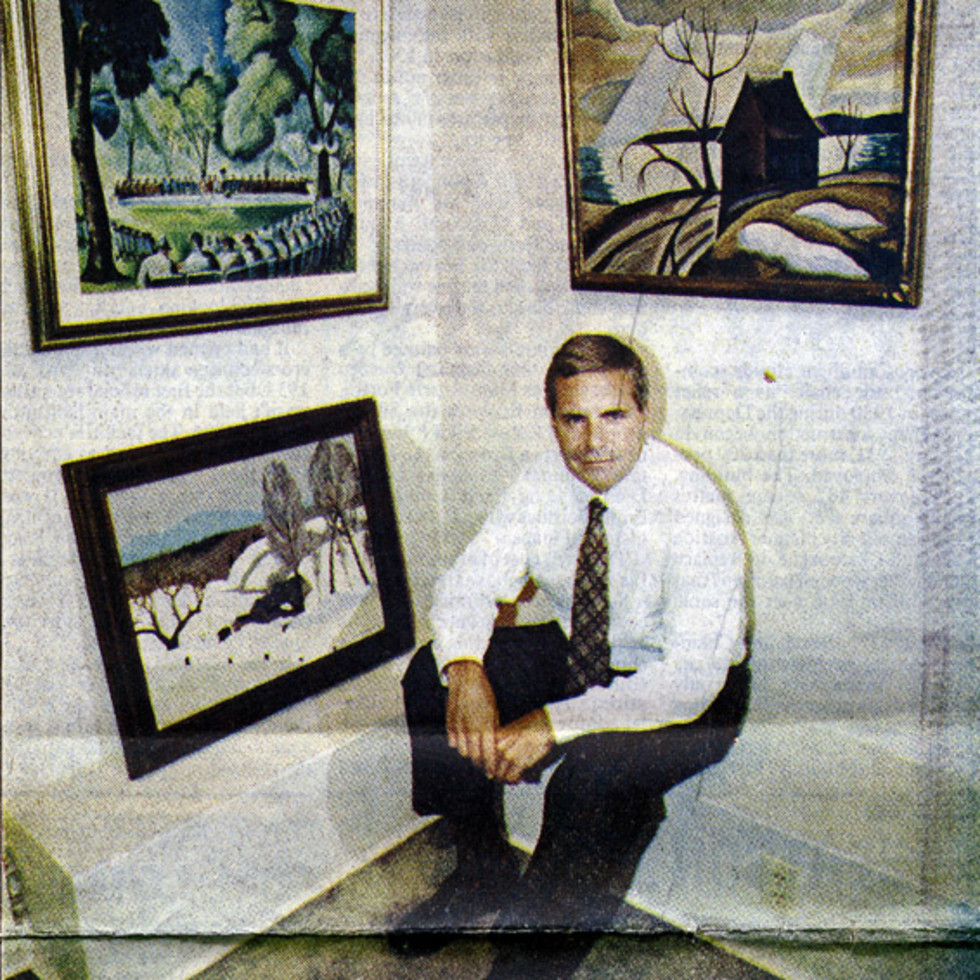

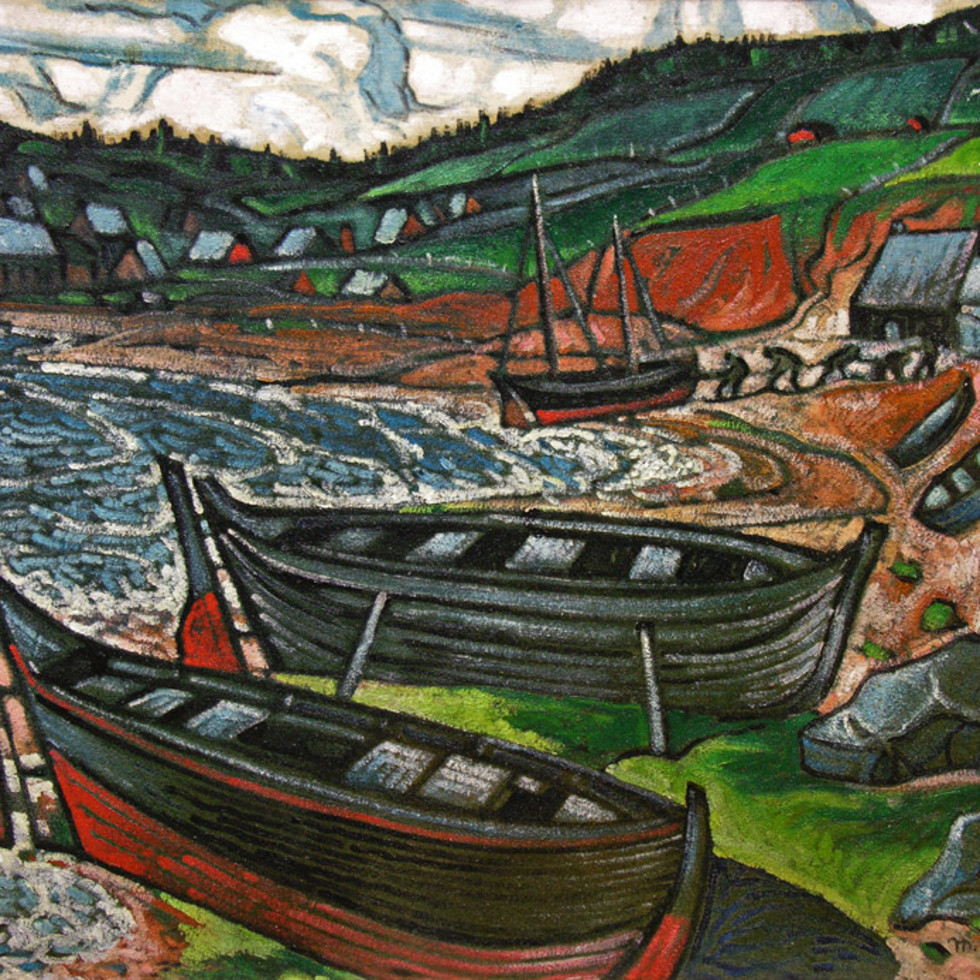

Heward is not remembered primarily for her landscapes, but The North River, Autumn (1935) in this Exhibition certainly supports Ayre's opinions. Another outstanding landscape, Rockliffe Village, was reproduced in Saturday Night in April of 1935. Painting shapes against shapes, Heward portrays patchwork fields, abstracted trees and a ribbon road which disappears and reappears, circling its way through the undulating distance.

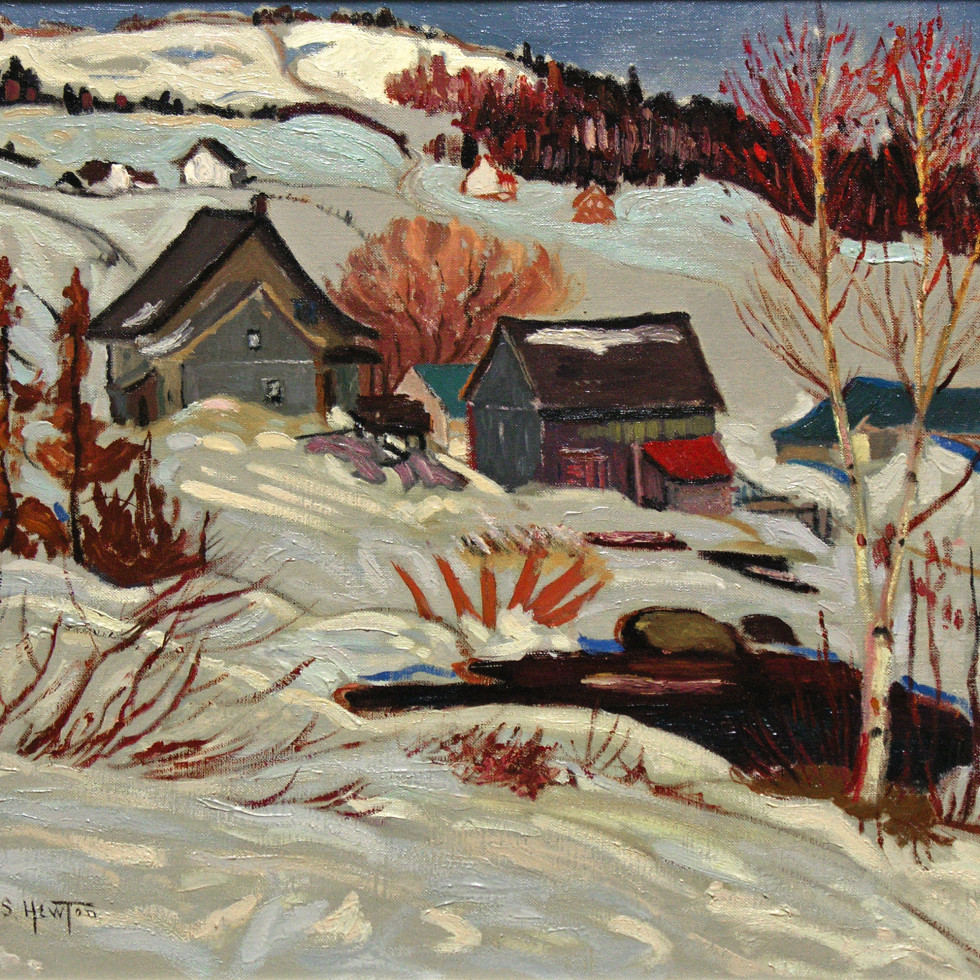

While titles of works exhibited indicate that she painted at Georgian Bay in Ontario and in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, most of her small oil-on-panel sketches were done near Fernbank, her family summer home outside of Brockville, Ontario. Here A.Y. Jackson, Sarah Robertson, Isabel McLaughlin and two of her summer neighbours, Ruth and Charles Eliot of Ottawa, joined in what Jackson called "painting picnics."

Her family has said that Prudence and her friends only painted at Fernbank in the autumn, and A.Y. Jackson in his Memorial Exhibition catalogue introduction describes the countryside of some of Heward's sketches:

"It was typical lower Ontario country, flat for the most part but with the rock cropping out of the shallow soil... The subjects were weatherbeaten barns and silos, little wooden churches, pasture fields and scattered wood lots with their pines, maples and elms."

There was a serene beauty to many of Prudence's sketches of this region. They were boldly simplified and solidly painted with the deep green of the pines, the silver-grey barns and sun bleached fields and such wild flowers as milkweed, iris and mullein to enliven the foreground.

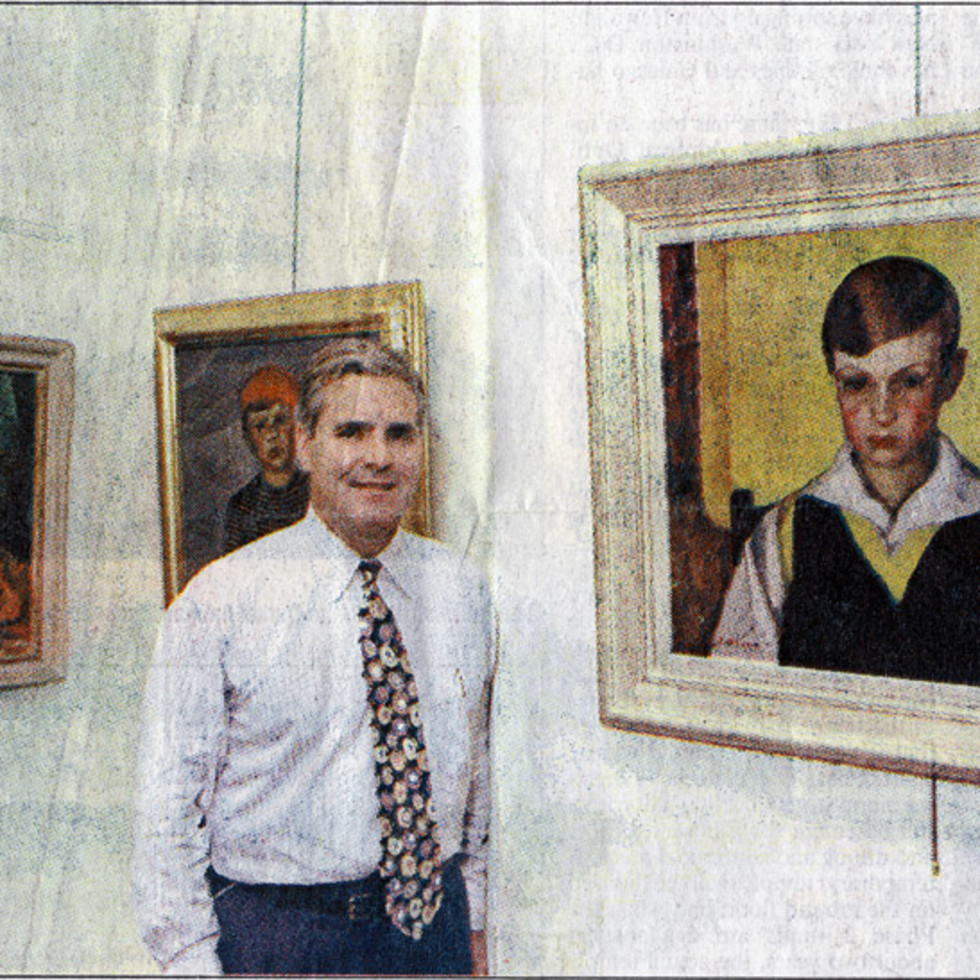

Many of these small sketches are charming. Equally so, and often filled with rich colour, bright or moody, are her still-life paintings, Tulips, 1933, Petunias, ca. 1930, or arrangements of fruit, Fruit in the Grass, ca. 1939. More commanding are her studies of young boys, Heward Grafftey, 1936 and Rosaire, 1935, MMFA. The latter work is a young boy seated beside a staircase and is painted with the early expertise she demonstrated in Two Sisters of Quebec. In each the emphasis is on the interplay between angles and planes in objects and figures. The palette is the same in each painting, but for Rosaire, Heward has worked her colours with greater sophistication. The shading she uses in the boy's coat, and the twist of the staircase, give the viewer a sense of movement in what appears to be a static situation. It is one of her most compelling works.

It was rare for Heward to paint or sketch a young man. The majority of her sitters were white women, members of her family, Quebec country girls and women of colour she hired to pose in her studio. She considered that she painted figures not portraits, and in her figure work she recorded universal and timeless characteristics of womanhood: fear, suspicion, boredom, shyness, sadness and resignation.

Her characterizations are thought-provoking and subtle, but why, with few exceptions, did she portray the less happy aspects of women's spirits? Heward was trained to observe and to record what she saw. Much of her life was lived during the two World Wars and the Great Depression. Her sister and brothers were in England and France during the First War. Inevitably there was emotional hardship for the rest of the family.

In the 1930's Heward became involved in helping young people who suffered because of the Depression. She lived in times that made a thoughtful, reflective woman understand the emotions which accompanied need, whether for food, self respect, love or companionship. Her family says she was an unerring judge of character. We can see that she was as gifted in her ability to portray the spirit of her subject as she was in constructing her figure on the surface of the canvas, or reproducing the colour values of her skin.

Do the expressions on the faces of Heward's figures reflect her own attitudes to life? One can only guess. Anecdotes reveal that she was a woman of spirit. Once, when she was thoroughly angry about the hanging of a Canadian Group exhibition at the Art Association of Montreal, she went with her friend Sarah Robertson and began to rehang it. They were stopped by Arthur Lismer - and for sometime Heward was persona non grata in the gallery.

Though Heward was not robust in the physical sense, she was tough minded in her dedication to her work. One feels that she has portrayed something of hew own temperament in Rolland, painted near the beginning of her career, and in Farmer's Daughter painted near the end.

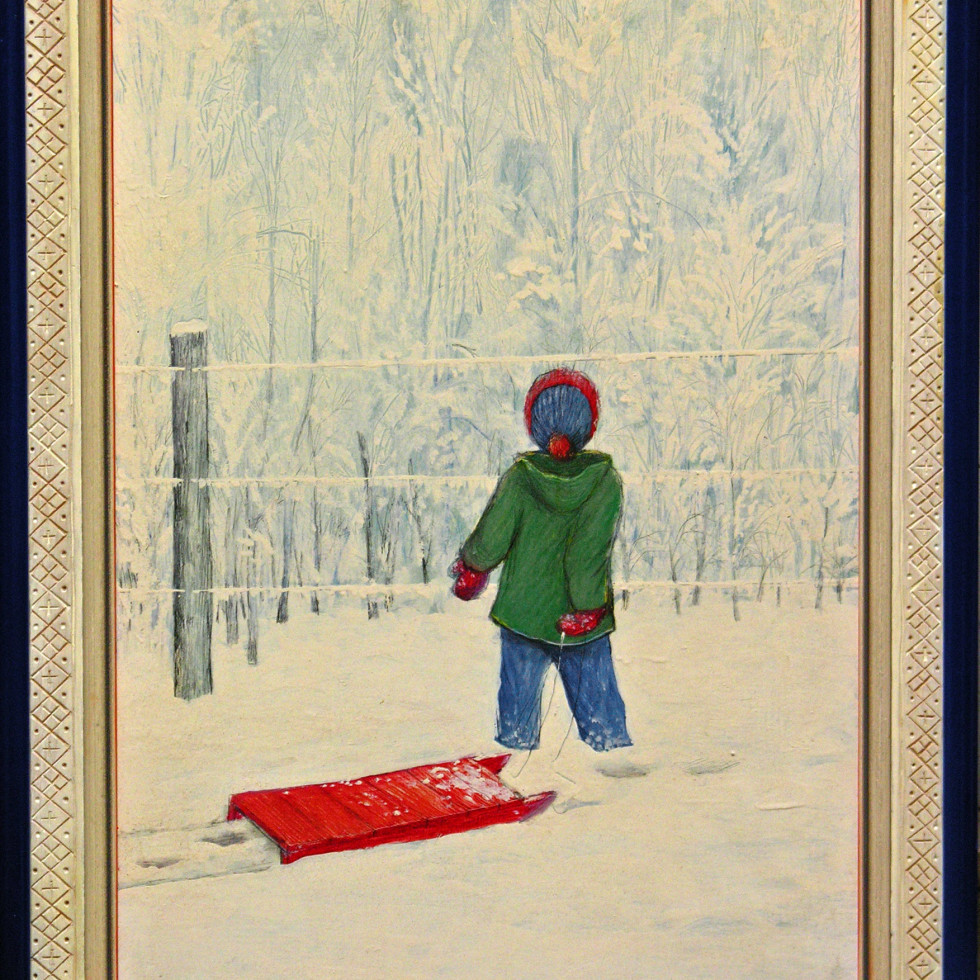

The faces in Heward's paintings of little girls carry emotions similar to those of her adult figures and these paintings are a very special part of her work. Among them are Clytie (1938, PC), Farmhouse Window (1938, AGH), Little Girl with an Apple (1943), and small sketches and portraits of her nieces, Efa, Barbara, Faith and Anne. The Toronto art critic, Paul Duval, writing in Saturday Night of April 1948, called Barbara (1933) "as consummate a picture as any she painted."

It is, in fact, one of the strongest paintings of children in Canadian art. One is struck by the expression on the child's face, that of a serious little girl intent on her deportment, doubtless expected to behave through each of many sittings. We are absorbed by her rich pink dress and the lush green foliage. It is strong satisfying colour. A fat shaft of Barbara's dutch-cut hair is pulled back and tied with a plump bow. The neck of her dress and the edge of the sleeves are decorated with a threaded ribbon glazed or varnished to ruby red.

Barbara is an interesting statement of colour theory and a sensitive character study. The little dress was originally a print or polka dot quite unrelated to the startling pink Heward chose to paint it. While the child is wistful, she is not without resolution, and her strength has been reinforced by the frontality of her figure complemented by the strong verticals of the plants immediately behind her.

For many sittings the young model was given paint brushes to hold and promised milk and cookies. At the last sitting a small nosegay was placed in her hands, a posy which makes a perfect little highlight in the painting.

Farmhouse Window, the work of a mature artist, is more intuitive than Barbara and in it Heward allows herself to be more suggestive than specific. This can be seen in the way she paints the drapes, the flower in its tin and the texture of the child's dress. Edges are softened, and indeed the free way in which Heward uses her paint is an indication at the middle of her career that her ultimate destination as an artist was away from formal considerations towards gentle expressionism.

In January of 1938, Heward included two paintings of black women, Hester, 1937 and A Young Coloured Girl in a Canadian Group of Painters Exhibition held at the Montreal Art Association. It was unusual to choose a black model in Canada in the thirties, but Heward had already shown her interest in rich skin tones in Rolland, Rosaire and Sisters of Rural Quebec, young people who lived close to the land, their skin sun-soaked and nut brown. In addition, Heward visited Bermuda with Isabel McLaughlin and Yvonne Housser and it is probable that her observations of people on the island reinforced her interest in capturing the richness of brown skin in paint.

The present exhibition contains a number of examples of her work with black models, Hester, Girl in the Window (1941) and an untitled work. The untitled work is a painting of a woman set in sunflowers, with a field of wheat stooks in the distance. Its most striking feature is Heward's golden palette, derived from the autumn sketches she did with her friends in Brockville and the Laurentians. The whole work reflects the bounty of that time of year: it is not difficult to draw a parallel between the harvest of the land and the strong ripe beauty of the woman's breast and body.

The little landscape study for this radiant painting is in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada and is titled Sunflowers.

The study for Girl in the Window is Backyard St. Famille Street (ca. 1940). In spirit, Girl in the Window is the antithesis of the beautiful woman surrounded with sunflowers. For this work Heward paints with her earlier palette, but all the colours are subdued. The whole effect is one of softness. Here Heward has abandoned strong outlines and planes. She wants to be aware of the soft texture of the girl's skin, of her wooly sweater, and the transparent curtain draped behind her head.

This is Heward at her most subtle and sophisticated. While painting soft textures, she manages at the same time to create a psychologically harsh environment and to depict a woman who seems to have been abandoned. What does her look express, is it resignation or regret? Ultimately Heward's beauty was truth, and nowhere more than in her paintings of black women is this made clear.

Within a year after Girl in the Window, using the same palette but with the values increased to the intensity of carnival colours, Heward painted what appears to be one of her most spontaneous works, Still Life with Eggplant (1943, AGW). It is rich and happy. All the interesting composition and movement in the still life is cleverly balanced by the colours and the rigid structures of the window frame and the buildings beyond. Fauve, it is a marvelous expression of the artist's delight in working with paint. The intensity of this painting is well matched by Farmer's Daughter, painted two years later and called by Dennis Reid, "aggressively beautiful."

To the end of her career and within the framework of her environment, Prudence Heward remained a "modern." She was not a revolutionary, and it is unlikely had she lived longer that she would have followed younger Montreal artists into the world of the purely abstract. Since her first little "sketch" was hung in the Spring Exhibition of 1920, her paintings have frequently been shown in Canada and abroad. She never had a "following;" she neither taught nor wrote. She devoted herself to her painting, set herself painterly problems, and went about solving them with originality and distinction.

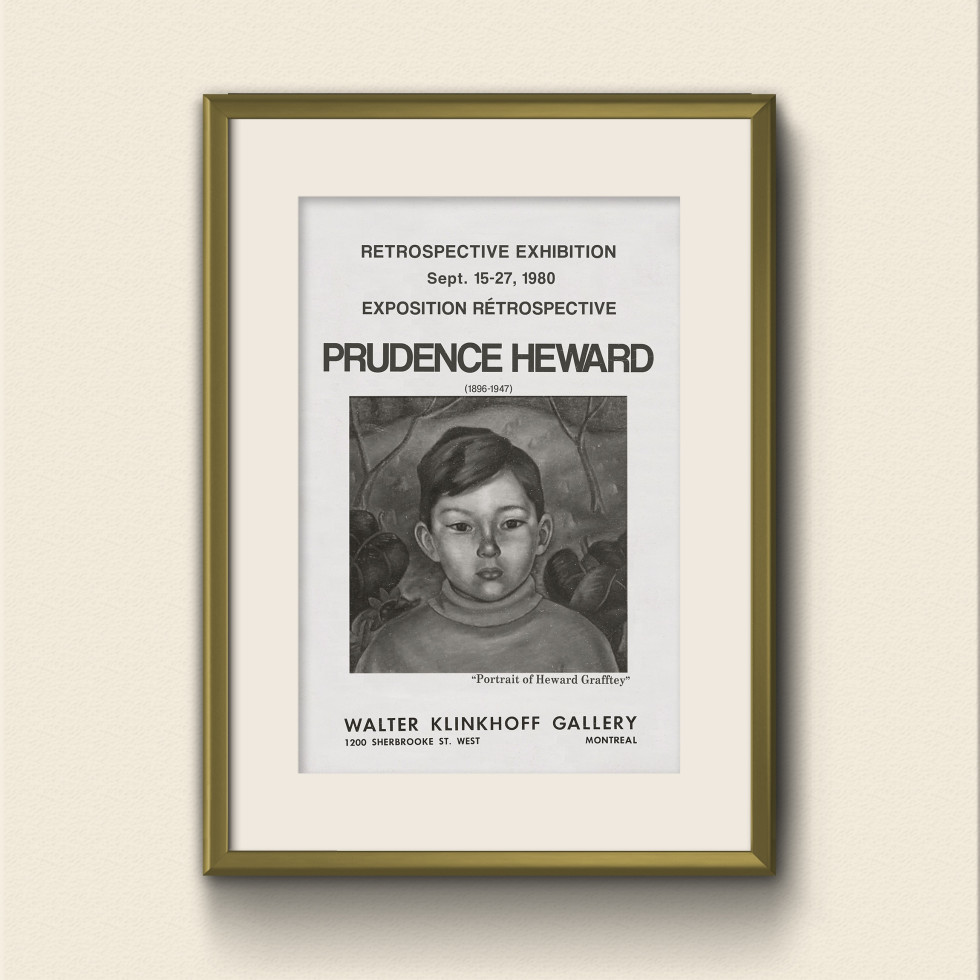

Source: Prudence Heward Retrospective Exhibition Catalogue, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff (1980). Text "Prudence Heward: An Introduction to Her Life and Work" written by Janet Braide. Limited edition catalogue SOLD OUT.

© Copyright Janet Braide and Galerie Walter Klinkhoff Inc.